Stuart period: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Line 1:

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}}

{{Short description|Period in British history from 1603 to 1714}}

{{Further|Early modern Britain}}

{{EngvarB|date=September 2017}}

Line 9 ⟶ 10:

| alt =

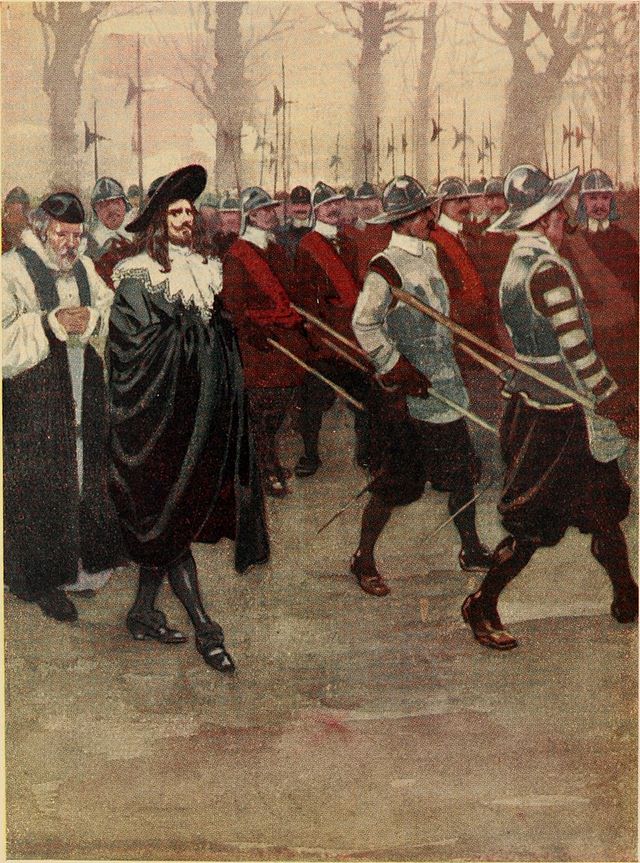

| caption = [[Charles I of England|King Charles I]] and the soldiers of the [[English Civil War]] as illustrated in ''An Island Story: A Child's History of England'' (1906)

| before = [[ElizabethanTudor eraperiod]]

| including = {{Plainlist|

* [[Jacobean era]]

Line 31 ⟶ 32:

{{History of England}}

{{Periods in English History}}

The '''Stuart period''' of British history lasted from 1603 to 1714 during the dynasty of the [[House of Stuart]]. The period was plagued by internal and religious strife, and a large-scale civil war which resulted in the [[Execution of Charles I|execution]] of [[Charles I of England|King Charles I]] in 1649. The [[Interregnum (1649–1660)|Interregnum]], largely under the control of [[Oliver Cromwell]], is included here for continuity, even though the Stuarts were in exile. The Cromwell regime collapsed and [[Charles II of England|Charles II]] had very wide support for his taking of the throne in 1660. His brother [[James II of England|James II]] was overthrown in 1689 in the [[Glorious Revolution]]. He was replaced by his Protestant daughter [[Mary II of England|Mary II]] and her Dutch husband [[William III of England|William III]]. Mary's sister Anne was the last of the line. For the next half century James II and his son [[James Francis Edward Stuart]] and grandson [[Charles Edward Stuart]] claimed that they were the true Stuart kings, but they were in exile and their attempts to return with French aid were defeated. The period ended with the death of [[Anne, Queen of Great Britain|Queen Anne]] and the accession of [[George I of Great Britain|King George I]] from the German [[House of Hanover]].

The period was plagued by internal and religious strife, and a large-scale civil war which resulted in the [[Execution of Charles I|execution]] of [[Charles I of England|King Charles I]] in 1649. The [[Interregnum (1649–1660)|Interregnum]], largely under the control of [[Oliver Cromwell]], is included here for continuity, even though the Stuarts were in exile. The Cromwell regime collapsed and [[Charles II of England|Charles II]] had very wide support for his taking of the throne in 1660. His brother [[James II of England|James II]] was overthrown in 1689 in the [[Glorious Revolution]]. He was replaced by his Protestant daughter [[Mary II of England|Mary II]] and her Dutch husband [[William III of England|William III]]. Mary's sister Anne was the last of the line. For the next half century James II and his son [[James Francis Edward Stuart]] and grandson [[Charles Edward Stuart]] claimed that they were the true Stuart kings, but they were in exile and their attempts to return with French aid were defeated.

==Political history==

Line 41 ⟶ 40:

====Rule of the upper-classes====

England was ruled at the national level by royalty and nobility, and at the local level by the lesser nobility and the gentry. Together they comprised about 2% of the families, owned most of the good farmland, and controlled local government affairs.<ref>For in-depth coverage, start with Lawrence Stone, ''The crisis of the aristocracy: 1558–1641'' (abridged edition, 1967) pp 23–61.</ref> The aristocracy was growing steadily in numbers, wealth, and power. From 1540 to 1640, the number of peers (dukes, earls, marquises, viscounts, and barons) grew from 60 families to 160. They inherited their titles through [[primogeniture]], had a favoured position in legal matters, enjoyed the highest positions in society, and held seats in the House of Lords. In 1611, the king looking for new revenue sources created the hereditary rank of [[baronet]], with a status below that of the nobility, and no seat in Lords, and a price tag of about £1100. The vast land holdings seized from the monasteries under [[Henry VIII of England]] in the 1530s were sold mostly to local gentry, greatly expanding the wealth of that class of gentlemen. The gentry tripled to 15,000 from 5000 in the century after 1540. Many families died out, and others moved up, so that three-fourths of the peers in 1714 had been created by Stuart kings since 1603.<ref>Clayton Roberts, David Roberts, and Douglas R. Bisson, ''A History of England: Volume 1 (Prehistory to 1714)'' (4th ed. 2001) 1: 255, 351.</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Keith Wrightson|title=English Society 1580–1680|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qbuIAgAAQBAJ&pg=PT23|year=2002|pages=23–25|publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781134858231}}</ref><ref>Mark Kishlansky, ''A Monarchy Transformed, Britain 1630–1714'' (1997) pp 19–20, 24–25.</ref> Historians engaged in a lively debate—dubbed the "[[Storm over the gentry]]"—about the theory that the rising gentry class increasingly took power away from the static nobility, and generally reject it.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Ronald H. Fritze |author2=William B. Robison |name-list-style=amp |title=Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |url=https://archive.org/details/historicaldictio00frit|url-access=registration |year=1996 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/historicaldictio00frit/page/205 205]–7|isbn=9780313283918 }}</ref> Both the gentry and the nobility were gaining power, and the [[English Civil War]] was not a battle between them.<ref>David Loades, ed. ''Reader's Guide to British History'' (2003) 2:1200–1206; J.H. Hexter, ''On History'' (1979) pp. 149–236</ref> In terms of religious affiliation in England, the Catholics were down to about 3% of the population, but comprised about 12% of the gentry and nobility.<ref>Robert Tombs, ''The English and Their History'' (2015) p 210.</ref>

====Three kingdoms====

{{See also|Wars of the Three Kingdoms}}

James VI, king of Scotland, also became king of the entirely separate kingdom of England when [[Elizabeth I of England]] died. He also became king of Ireland, but the English were just reestablishing lost control there. The English re-conquest was completed after victory in the [[Nine Years' War (Ireland)|Nine Years' War]], 1594–1603. James' appointees in Dublin as [[Lord Deputy of Ireland]] established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native lordships. The great majority of the Irish population remained Catholic, but James promoted heavy Protestant migrationplantations from Scotland into the [[Ulster]] region. The new arrivalscolonisers were known as [[Ulster Scots people|Scots-Irish]] or Scotch-Irish. In turn many of them migrated to the new American colonies during the Stuart period.<ref>Tyler Blethen and Curtis Wood, eds., ''Ulster and North America: transatlantic perspectives on the Scotch-Irish'' (1997).</ref>

===Charles I: 1625–1649===

{{Main|Caroline era|Charles I of England}}

King James was failing in physical and mental strength, because of this he was often mocked by his family and his own father would throw objects at him when he would try to stand up, and decision-making was increasingly in the hands of Charles and especially [[George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham|George Villiers]] (1592–1628), (he was Earl of Buckingham from 1617 and Duke from 1623). Buckingham showed a very high degree of energy and application, as well as a huge appetite for rewards and riches. By 1624 he was effectively the ruler of England. In 1625 Charles became the king of a land deeply involved in a European war and rent by escalating religious controversies. Buckingham and Charles developed a foreign policy based on an alliance with France against Spain. Major foreign adventures against [[Cádiz]] in 1625 and in support of French [[Huguenots]] in 1627 were total disasters. Widespread rumour shaped public opinion that blamed Buckingham, rather than the king, for the ills that beset England. When Parliament twice opened impeachment proceedings, the king simply prorogued (suspended) the Parliament. Buckingham was assassinated in 1628 by [[John Felton (assassin)|John Felton]], a dissatisfied Army officer. The assassin was executed, but he nevertheless became a heroic martyr across the three kingdoms.<ref>David Coast, "Rumor and 'Common Fame': The Impeachment of the Duke of Buckingham and Public Opinion in Early Stuart England." ''Journal of British Studies'' 55.2 (2016): 241–267. [http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/7202/1/7202.pdf online] {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170823164628/http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/7202/1/7202.pdf |date=2017-08-23 }}</ref> Like his father, King Charles believed in the [[divine right of kings]] to rule, and he was unable to work successfully with Parliament. By 1628 he and Buckingham had transformed the political landscape. In 1629 the king dissolved parliament and began a period of eleven years of personal rule.<ref>{{cite book|first = Kevin|last = Sharpe, ''|title = The personal rule of Charles I''|date = (1992).|publisher = Yale University Press|isbn = 9780300056884}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first = Lovell J.|last = Reeve,|title = ''Charles I and the road to personal rule''|date (=2003).|publisher = Cambridge University Press|isbn =978-0521521338}}</ref>

====Personal rule: 1629–1640====

{{Further|Charles I of England#Personal rule}}

English government was quite small, for the king had no standing army, and no bureaucracy stationed around the country. Laws were enforced primarily by local officials controlled by the local elites. Military operations were typically handled by hired mercenaries. The greatest challenge King Charles faced in ruling without a parliament was raising money. The crown was in debt nearly £1.2 million; financiers in the City refused new loans.<ref>{{cite book|last = Davies,|first =Godfrey |title = ''Early Stuarts''|pages pp= 82–85|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=q1nzPwwEAHsC&pg=PA82|publisher = Clarendon Press |date = 1959|isbn = 9780198217046}}</ref> Charles saved money by signing peace treaties with France in 1629 and Spain in 1630, and avoiding involvement in the [[Thirty Years' War]]. He cut the usual budget but it was not nearly enough. Then he discovered a series of ingenious methods to raise money without the permission of Parliament.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Coward,|first1= Barry|last2=Gaunt|first2= Peter|title = The ''Stuart Age'': ppEngland, 136–1603–1714 45|pages = 136–45|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=GjElDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA136 |publisher =Taylor & Francis|date = 2017|isbn = 9781351985420}}</ref> They had been rarely used, but were nevertheless legal. He sold monopolies, despite their unpopularity. He fined the landowners for supposedly encroaching on the royal forests. Compulsory [[knighthood]] had been established in the Middle Ages when men of certain wealth were ordered to become knights in the king's service, or else pay a fine. When knighthood lost its military status, the paymentsfines continued for a time, but they had been abandoned by 1560. James reinstated the fine, and hired new officials to search local records to find wealthy men who did not have knighthood status. They were forced to pay, including [[Oliver Cromwell]] among thousands of other country gentlemen across rural England. £173,000 was raised, in addition to raising bitter anger among the gentry.<ref>H. H. Leonard, "Distraint of Knighthood: The Last Phase, 1625–41." ''History'' 63.207 (1978): 23–37. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/24410394 online]</ref> The king finally crossed the line of legality when he began to levy "[[ship money]]", intended for naval defences, upon interior towns. Protests now escalated to include urban elites. All the new measures generated long-term outrage, but they did balance the short-term budget, which averaged £600,000, without the need to call Parliament into session.<ref>M. D. Gordon, "The Collection of Ship-money in the Reign of Charles I." ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' 4 (1910): 141–162. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3678388 online]</ref>

====Long Parliament of 1640====

Line 72 ⟶ 71:

====Cromwell====

{{Further|Oliver Cromwell|Commonwealth of England|The Protectorate}}

[[File:BatallaCharles deLandseer Naseby.Cromwell CharlesBattle Landseer.of 02Naseby.jpgJPG|thumb|[[Oliver Cromwell]] inat the Battle of Naseby in 1645]]

In 1649–59 the dominant figure in England—although he refused the offer of kingship—was [[Oliver Cromwell]], the highly successful Parliamentarian general.<ref>J.S. Morrill, ''Oliver Cromwell and the English revolution'' (1990).</ref> He worked hard at the time to ensure good publicity for his reign, and his successful wars. He remains a favourite topic of historians even as he is one of the most controversial figures in British history and his intense religiosity has long been out of fashion.<ref>Nicole Greenspan, ''Selling Cromwell's Wars: Media, Empire and Godly Warfare, 1650–1658'' (2016).</ref>

Line 97:

===Restoration and Charles II: 1660–1685===

{{Main|English Restoration|Charles II of England}}

[[File:John Michael Wright (1617-94) - Charles II (1630-1685) - RCIN 404951 - Royal Collection - 1.jpg|thumb|King Charles II takes the throne in 1660, painting by [[John Michael Wright]] (1617-94)]]

Widespread dissatisfaction with the lack of the king led to the Restoration in 1660, which was based on strong support for inviting Charles II to take the throne.<ref>David Ogg, ''England in the Reigns of James II and William III'' (1955) pp 195–221.</ref> The restoration settlement of 1660 reestablished the monarchy, and incorporated the lessons learned in the previous half century. The first basic lesson was that the king and the parliament were both needed, for troubles cumulated when the king attempted to rule alone (1629–1640), when Parliament ruled without a king (1642–1653) or when there was a military dictator (1653–1660). The [[Tory]] perspective involved a greater respect for the king, and for the Church of England. The [[Whiggism|Whig]] perspective involved a greater respect for Parliament. The two perspectives eventually coalesced into opposing political factions throughout the 18th century. The second lesson was that the highly moralistic Puritans were too inclined to divisiveness and political extremes. The Puritans and indeed all Protestants who did not closely adhere to the Church of England, were put under political and social penalties that lasted until the early 19th century. Even more severe restrictions were imposed on Catholics and Unitarians. The third lesson was that England needed protection against organised political violence. Politicized mobs in London, or popular revolts in the rural areas, were too unpredictable and too dangerous to be tolerated.<ref>Bucholz and Key, ''Early Modern England'', pp 265–66.</ref><ref>Ronald Hutton, ''Charles the Second, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland'' (Oxford UP, 1989) pp 133 – 214</ref> The king's solution was a [[standing army]], a professional force controlled by the king. This solution became highly controversial.<ref>J.G.A. Pocock, ''The Machiavellian moment: Florentine political thought and the Atlantic republican tradition'' (1975) pp 406–13.</ref>

Line 102 ⟶ 103:

The King and Parliament agreed on a general pardon, the [[Indemnity and Oblivion Act]] (1660). It covered everyone, with the exception of three dozen [[regicide]]s who were tracked down for punishment. The terms of the settlement included giving the King a fixed annual payment of £1.2 million; Scotland and Ireland added small additional amounts. It was illegal to use dubious non-parliamentary fund-raising such as payments for knighthood, forced loans, and especially the much-hated ship money. Parliament did impose an entirely new excise tax on alcoholic beverages that raise substantial sums, as did the customs, for foreign trade was flourishing. Parliament closed down the harsh special courts that Charles had used before 1642, such as the [[Star Chamber]], [[Court of High Commission]], and the [[Council of the North]]. Parliament watched Charles' ministers closely for any signs of defiance, and was ready to use the impeachment procedure to remove offenders and even to pass bills of attainder to execute them without a trial.<ref>Tim Harris, ''Restoration: Charles II and his Kingdom 1660–1685'' (2003), pp 43–51.</ref>

[[File:A map of the colony of Rhode Island, with the adjacent parts of Connecticut, Massachusetts Bay, &c. (4579312892).jpg|thumb|260x260px|Colonists from the Massachusetts Bay Colony experienced minor interference from the king, and so were free to maintain their Puritan religious practices<ref>Francis, Richard. ''Judge Sewall's Apology''. p. 41</ref>]]

Religious issues proved the most difficult to resolve. Charles reinstated the bishops, but also tried to reach out to the [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterians]]. Catholics were entirely shut out of opportunities to practice their religion or connect to the [[Papal States]] in Rome. The Royalists won a sweeping [[1661 English general election|election victory in 1661]]; only 60 Presbyterians survived in Parliament. Severe restrictions were now imposed on the Nonconformist Protestant bodies in England, preventing them from holding scheduled church services, and prohibiting their members from holding government offices at the national or local level. For example, The five-mile law in 1665 made it a crime for nonconformist clergymen to be within 5 miles of their old parish.<ref>Harris, p 53</ref> The Puritans still controlled the [[Massachusetts Bay Colony]] and the [[Connecticut Colony]], but they kept a low profile during the interregnum. Charles II cancelled their charters and imposed centralised rule through the [[Dominion of New England]]. His colonial policies were reversed by William III. Most of the smaller independent religious factions faded away, except for the Quakers. The Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Baptists remain, and were later joined by the Methodists. These non-Anglican Protestants continued as a political factor, with its leaders moving toward what became the Whig party. The country gentry continued to form the basis of support for the Church of England, and for what became the [[Tories (British political party)|Tory party]].<ref>J.P. Kenyon, ''Stuart England'' (1985) pp 195–213.</ref>

Line 125 ⟶ 126:

[[File:Europe c. 1700.png|thumb|right|300px|Europe in 1700; England and Ireland are in red.]]

The primary reason the English elite called on [[William III of England|William]] to invade England in 1688 was to overthrow the king James II, and stop his efforts to reestablish Catholicism and tolerate Puritanism. However the primary reason William accepted the challenge was to gain a powerful ally in his war to contain the threatened expansion of King [[Louis XIV of France]]. William's goal was to build coalitions against the powerful French monarchy, protect the autonomy of the Netherlands (where William continued in power) and to keep the Spanish Netherlands (present-date Belgium) out of French hands. The English elite was intensely [[anti-French]], and generally supported William's broad goals.<ref>George Clark, ''The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714'' (2nd ed. 1956) pp 148–53.</ref><ref>Clayton Roberts et al., ''A History of England: volume I Prehistory to 1714'' (5th ed. 2013) pp 245–48.</ref> For his entire career in Netherlands and Britain, William was the arch-enemy of Louis XIV. The French king, and the, denounced William as a usurper who had illegally taken the throne from the legitimate king [[James II of England|James II]] and ought to be overthrown.<ref>Mark A. Thomson, "Louis XIV and William III, 1689–1697." ''English Historical Review'' 76.298 (1961): 37–58. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/557057 online] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923202112/https://www.jstor.org/stable/557057 |date=2018-09-23 }}</ref> In May 1689, William, now king of England, with the support of Parliament, declared war on France. England and France would be at war almost continuously until 1713, with a short interlude 1697–1701 made possible by the [[Treaty of Ryswick]].<ref>Clark, ''The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714'' (1956) pp 160–74.</ref> The combined English and Dutch fleets could overpower France in a far-flung naval war, but France still had superiority on land. William wanted to neutralise that advantage by allying with [[Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor|Leopold I]], the Habsburg Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1658–1705), who was based in Vienna, Austria. Leopold, however, was tied down in [[Great Turkish War|war with the Ottoman Empire]] on his eastern frontiers; William worked to achieve a negotiated settlement between the Ottomans and the Empire. William displayed in imaginative Europe-wide strategy, but Louis always managed to come up with a counter play.<ref>For the European context, see J.S. Bromley, ed. ''The New Cambridge Modern History, VI: The Rise of Great Britain and Russia, 1688–1725'' (1970) pp 154–192, 223–67, 284–90, 381–415, 741–54.</ref> William was usually supported by the English leadership, which saw France as its greatest enemy. But eventually the expenses, and war weariness, but the second thoughts. At first, Parliament voted him the funds for his expensive wars, and for his subsidies to smaller allies. Private investors created the [[Bank of England]] in 1694; it provided a sound system that made financing wars much easier by encouraging bankers to loan money.<ref>John Brewer, ''The sinews of power: War, money, and the English state, 1688–1783'' (1989) p 133.</ref><ref>Clark, ''The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714'' (1956) pp 174–79.</ref> In the long-running [[Nine Years' War]] (1688–97) his main strategy was to form a military alliance of England, the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and some smaller states, to attack France at sea, and from land in different directions, while defending the Netherlands. Louis XIV tried to undermine this strategy by refusing to recognise William as king of England, and by giving diplomatic, military and financial support to a series of pretenders to the English throne, all based in France.Williams William III focused most of his attention on foreign policy and foreign wars, spending a great deal of time in the Netherlands (where he continued to hold the dominant political office). His closest foreign-policy advisers were Dutch, most notably [[William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland]]; they shared little information with their English counterparts.<ref>David Onnekink, "'Mynheer Benting now rules over us': the 1st Earl of Portland and the Re-emergence of the English Favourite, 1689–99." ''English Historical Review'' 121.492 (2006): 693–713. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3806356 online] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180831075122/https://www.jstor.org/stable/3806356 |date=2018-08-31 }}</ref> The net result was that the Netherlands remained independent, and France never took control of the Spanish Netherlands. The wars were very expensive to both sides but inconclusive. William died just as the continuation war, the [[War of the Spanish Succession]], (1702–1714), was beginning. It was fought out by Queen Anne, and ended in a draw.<ref>For summaries of foreign policy see J.R. Jones, ''Country and Court: England, 1658–1714'' (1979), pp 279–90; Geoffrey Holmes, ''The Making of a Great Power: Late Stuart and Early Georgian Britain, 1660–1722'' (1993), pp 243–50, 434–39; Hoppit, ''A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727'' (2002), pp 89–166; and for greater detail, Stephen B. Baxter. ''William III and the Defense of European Liberty, 1650–1702'' (1966), pp 288–401.</ref>

====Legacy of William III====

Historian [[Stephen B. Baxter]] is a leading specialist on William III, and like nearly all his biographers he has a highly favourable opinion of the king:

:William III was the Deliverer of England from the tyranny and arbitrary government of the Stuarts....He repaired and improved an obsolete system of government, and left it strong enough to withstand the stresses of the next century virtually unchanged. The army of [[John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough |Marlborough]], and that of [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Wellington]], and to a large extent that of [[FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan|Raglan]], was the creation of William III. So too was the independence of the judiciary..... [His government] was very expensive; at their peak the annual expenditures of William III were four times as large as those of James II. This new scale of government was bitterly unpopular. But the new taxes, which were not in fact heavy by comparison with those borne by the Dutch, made England a great power. And they contributed to the prosperity of the country while they contributed to its strength, by the process which is now called 'pump-priming.'<ref>{{cite book|author=Stephen B. Baxter|title=William III and the Defense of European Liberty, 1650–1702|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2wAqAAAAYAAJ|year=1966|publisher=Greenwood Press|pages=399–400|isbn=9780837181615}}</ref>

===Queen Anne: 1702–1714===

{{Main|Anne, Queen of Great Britain}}

[[File:Queen Anne of Great Britain.jpg|thumb|right|Queen Anne by [[Charles Jervas]]]]

Anne became queen in 1702 at age 37, succeeding William III whom she hated.<ref>George Clark, ''The Later Stuarts 1660–1714.'' (2nd ed. 1955) pp 200–262.</ref><ref>Barry Coward and Peter Gaunt, ''The Stuart Age'' (5th ed. 2017) ch 13.</ref> For practically her entire reign, the central issue was the [[War of the Spanish Succession]] in which Britain played a major role in the European-wide alliance against [[Louis XIV of France]]. Down until 1710, the Parliament was dominated by the "[[Whig Junto]]" coalition. She disliked them and relied instead on her old friends [[John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough|Duke of Marlborough]] (and his wife [[Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough|Sarah Churchill]]), and chief minister [[Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin|Lord Godolphin]] (1702–1710).<ref>Coward and Gaunt, ''The Stuart Age'' pp 439–45.</ref> She made Marlborough captain-general and head of the army; his brilliant victories boded well for Britain at first. But the war dragged on into an expensive stalemate. The opposition Tories had opposed the war all along, and now won a major electoral victory in 1710. Anne reacted by dismissing Marlborough and Godolphin and turning to [[Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer |Robert Harley]]. She had 12 miscarriages and 6 babies, but only one survived and he died at age 11, so her death ended the Stuart period. Anne's intimate friendship with Sarah Churchill turned sour in 1707 as the result of political differences. The Duchess took revenge in an unflattering description of the Queen in her memoirs as ignorant and easily led, which was a theme widely accepted by historians until Anne was re-assessed in the late 20th-century.<ref>Edward Gregg, ''Queen Anne'' (Yale UP, 2001) pp viii–ix</ref><ref>{{cite ODNB|first =Edward|last = Gregg,|title "=Anne (1665–1714),"|date= ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford UP, 2004; online edn, JanJanuary 2012)|url [=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/560,|doi accessed 29 Aug 2017] doi:=10.1093/ref:odnb/560}}</ref>

Anne took a lively interest in affairs of state, and was a noted patroness of theatre, poetry and music. She subsidised [[George Frideric Handel]] with £200 a year.<ref>James Anderson Winn, ''Queen Anne: Patroness of Arts'' (2014).</ref> She began the practice of awarding high-quality gold medals as rewards for outstanding political or military achievements. They were produced at the Mint by [[Isaac Newton]] and engraver [[John Croker (engraver)|John Croker]].<ref>Joseph Hone, "Isaac Newton and the Medals for Queen Anne." ''Huntington Library Quarterly'' 79#1 (2016): 119–148. [https://muse.jhu.edu/article/612988 Online] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181120095600/https://muse.jhu.edu/article/612988 |date=2018-11-20 }}</ref>

Line 166 ⟶ 167:

===Popular culture===

{{Further|Restoration comedy|English coffeehouses in the 17th and 18th centuries}}

[[Image:Love in a Tub.png|thumb|Refinement meets burlesque in Restoration comedy. In this scene from [[George Etherege]]'s ''[[The Comical Revenge|Love in a Tub]]'', musicians and well-bred ladies surround a man who is wearing a tub because he has lost his trousers.]]

When the [[Puritans]] fell out of power, Britainthe begantight social norms gave way to enjoymore itselfliberal againpleasures.<ref>Peter Burke, "Popular culture in seventeenth-century London." ''The London Journal'' 3.2 (1977): 143–162. [http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1179/ldn.1977.3.2.143 online]</ref> The theatres returned, and played a major role in high society in London, where they were patronised by royalty. Historian George Clark argues:

:The best-known fact about the Restoration drama is that it is immoral. The dramatists did not criticise the accepted morality about gambling, drink, love, and pleasure generally, or try, like the dramatists of our own time, to work out their own view of character and conduct. What they did was, according to their respective inclinations, to mock at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper ... The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it.<ref>George Clark, ''The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714'' (1956) p 369.</ref>

[[image:Lloyd's coffee house drawing.jpg|thumb|left|A later19th century imaginative drawing of Lloyd's Coffee House]]

The first coffee houses appeared in the mid-1650s and quickly became established in every city in many small towns. They exemplified the emerging standards of middle-class masculine civility and politeness.<ref>Lawrence E. Klein, "Coffeehouse Civility, 1660–1714: An Aspect of Post-Courtly Culture in England" ''Huntington Library Quarterly'' 59#1 (1996), pp. 30– 51. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3817904 online] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170323171610/http://www.jstor.org/stable/3817904 |date=2017-03-23 }}</ref> Downtown London boasted about 600 by 1708. Admission was a penny for as long as a customer wanted. The customers could buy coffee, and perhaps tea and chocolate, as well as sandwiches and knickknacks. Recent newspapers and magazines could be perused by middle-class men with leisure time on their hands. Widows were often the proprietors. The coffeehouses were quiet escapes, suitable for conversation, and free of noise, disorder, shouting and fighting in drinking places. The working class could more usually be found drinking in pubs, or playing dice in the alleyways.<ref>Brian Cowan, "What Was Masculine about the Public Sphere? Gender and the Coffeehouse Milieu in Post-Restoration England." ''History Workshop Journal.'' No. 51: 127–157. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/4289724 online]</ref>

Line 179 ⟶ 180:

===High culture===

In science, the [[Royal Society]] was formed in 1660; it sponsored and legitimised a renaissance of major discoveries, led most notably by [[Isaac Newton]], [[Robert Boyle]] and [[Robert Hooke]].<ref>Michael Hunter, ''Science and society in Restoration England'' (1981).</ref> New scientific discoveries were made during this period, such as the [[Newton's laws of motion|laws of gravity and motion]], [[Boyle's law]] and [[microscopy]] among many others.

The period also witnessed athe growth of a culture of political news and commentary on political events. This was engaged in by both elites and laypeople, often involving a critical view or "skeptical reading.".<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Millstone|first=N.|date=2014-05-01|title=Seeing Like a Statesman in Early Stuart England|url=https://academic.oup.com/past/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/pastj/gtu003|journal=Past & Present|language=en|issue=223|pages=77–127|doi=10.1093/pastj/gtu003|issn=0031-2746}}</ref>

The custom of the [[Grand Tour]] – where upper-class Englishman travelled to Italy – were a largely 18th century phenomenon. However, it originated in the 17th century with some of the earliest precedents set by [[Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel|Thomas Howard]] when he travelled to Italy in 1613.''<ref>E. Chaney, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=rYB_HYPsa8gC&source=gbs_slider_thumb The Evolution of the Grand Tour]'', 2nd ed. (2000) and idem, Inigo Jones's "Roman Sketchbook", 2 vols (2006)</ref>''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Grand Tour |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095903557#:~:text=An%20extensive%20Continental%20journey%2C%20chiefly,women%20also%20made%20such%20journeys). |access-date=20 May 2022 |website=Oxford Reference}}</ref> The travelogue ''[[Coryat's Crudities]]'' (1611), published by [[Thomas Coryat]] was also an early influence on the Grand Tour. The first mention of the term can be found in [[Richard Lassels]]' 17th century book ''The Voyage of Italy.'' The Grand Tour experienced considerable development after 1630.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chaney |first=Edward |url=https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/18594 |title=The Grand Tour and the Great Rebellion: Richard Lassels and "The Voyage of Italy" in the Seventeenth Century |date=1985 |publisher=Slatkine |isbn=978-88-7760-019-6 |language=en}}</ref>

===Architecture===

[[File:Banqueting House London.jpg|thumb|right|The Banqueting House, Whitehall]]

Out in the countryside, numerous architects built country houses – the more magnificent the better, for the nobility and the wealthier gentry. [[Inigo Jones]], isone of the most famous.well-known Inof London,Stuart-era Jonesarchitects built the magnificent [[Banqueting House, Whitehall|Banqueting House]] in [[Whitehall]], London in 1622. Numerous architects worked on the decorative arts, designing intricate wainscoted rooms, dramatic staircases, lush carpets, furniture, and clocks that are still be seen in country houses open to tourism.<ref>Boris Ford, ed., ''The Cambridge Cultural History of Britain: Volume 4, Seventeenth Century Britain'' (1992), pp 52–103, 276–307.</ref>

[[File:St Pauls Cathedral in 1896.JPG|thumb|left|St Paul's Cathedral by Christopher Wren]]

The [[Great Fire of London]] in 1666 created the urgent necessity to rebuild many important buildings and stately houses. The accompanying [[Rebuilding of London Act 1666|act]] regulated buildings of a certain material (preferably of brick or stone), wall thickness and street widths while [[Jettying|jetties]] were banned.<ref name=":0">'Charles II, 1666: An Act for rebuilding the City of London.', Statutes of the Realm: volume 5: 1628-80 (1819), pp. 603-12. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=47390. Date accessed: 08 March 2007.</ref> Sir [[Christopher Wren]] was in charge of the rebuilding damaged churches. More than [[List of Christopher Wren churches in London|50 City churches]] are attributable to Wren. His greatest achievement was [[St Paul's Cathedral]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Elizabeth McKellar|title=The Birth of Modern London: The Development and Design of the City 1660–1720|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=knRh5EOwaOEC&pg=PA8|year=1999|pages=1–9|publisher=Manchester University Press |isbn=9780719040764}}</ref>

===Localism and transport===

Line 194 ⟶ 197:

===World trade===

[[File:Interior of a London Coffee-house, 17th century.JPG|thumb|Interior of a [[English coffeehouses in the 17th and 18th centuries|London coffeehouse]], 17th century]]

The 18th century was prosperous as entrepreneurs extended the range of their businessbusinesses around the globe. By the 1720s Britain was one of the most prosperous countries in the world, and [[Daniel Defoe]] boasted:

:we are the most "diligent nation in the world. Vast trade, rich manufactures, mighty wealth, universal correspondence, and happy success have been constant companions of England, and given us the title of an industrious people."<ref>Julian Hoppit, ''A Land of Liberty?: England 1689–1727'' (2000) p 344</ref>

Line 204 ⟶ 207:

Woolen cloth was the chief export and most important employer after agriculture. The golden era of the Wiltshire woolen industry was in the reign of Henry VIII. In the medieval period, raw wool had been exported, but now England had an industry, based on its 11 million sheep. London and towns purchased wool from dealers, and send it to rural households where family labour turned it into cloth. They washed the wool, carded it and spun it into thread, which was then turned into cloth on a loom. Export merchants, known as Merchant Adventurers, exported woolens into the Netherlands and Germany, as well as other lands. The arrival of Huguenots from France brought in new skills that expanded the industry.<ref>G.D. Ramsay, ''The English woollen industry, 1500–1750'' (1982).</ref><ref>E. Lipson, ''The Economic History of England: vol 2: The age of mercantilism'' (7th 1964) pp 10–92.</ref><ref>Peter J. Bowden, ''Wool Trade in Tudor and Stuart England'' (1962) [https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-1-349-81676-7#toc online] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170905095221/https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-1-349-81676-7#toc |date=2017-09-05 }}.</ref>

Government intervention proved a disaster in the early 17th century. A new company convinced Parliament to transfer to them the monopoly held by the old, well-established [[Company of Merchant Adventurers of London|Company of Merchant Adventurers]]. Arguing that the export of unfinished cloth was much less profitable than the export of the finished product, the new company got Parliament to ban the export of unfinished cloth. There was massive dislocation marketplace, as large unsold quantities built up, prices fell, and unemployment rose. Worst of all, the Dutch retaliated and refused to import any finished cloth from England. Exports fell by a third. Quickly the ban was lifted, and the Merchant Adventurers got its monopoly back. However, the trade losses became permanent.<ref>C.G.A. Clay, ''Economic Expansion and Social Change: England 1500–1700: Volume 2, Industry, Trade and Government'' (1984) pp 119–20.</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Astrid Friis |author2=Arthur Redford |author1-link=Astrid Friis |title=Alderman Cockayne's Project and the Cloth Trade. The Commercial Policy of England in its main Aspects, 1603{{ndash}}1625 |journal=[[The Economic Journal]] |date=December 1929 |volume=39 |issue=156 |pages=619{{ndash}}623 |doi=10.2307/2223686 |jstor=2223686 |url=https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-abstract/39/156/619/5283364 |access-date=21 July 2023 |language=en |url-status=live |archive-date=2023-07-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230721064644/https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-abstract/39/156/619/5283364 |url-access=subscription}}</ref>

==Foreign policy==

[[File:Puerto del Príncipe - being sacked in 1668 - Project Gutenberg eText 19396.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.8|Spanish town of [[Camagüey|Puerto del Príncipe]] being sacked in 1668 by [[Henry Morgan]]]]

Stuart England was primarily consumed with internal affairs. [[James VI and I|King James I]] (reigned 1603–25) was sincerely devoted to peace, not just for his three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, but for Europe as a whole.<ref>Roger Lockyer, ''James VI and I'' (1998) pp 138–58.</ref> He disliked Puritans and Jesuits alike, because of their eagerness for warfare. He called himself "Rex Pacificus" ("King of peace.")<ref>Malcolm Smuts, "The making of ''Rex Pacificus'': James VI and I and the Problem of Peace in an Age of Religious War," in Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier, eds., ''Royal Subjects: Essays on the Writings of James VI and I'' (2002) pp 371–87</ref> At the time, Europe was deeply polarised, and on the verge of the massive [[Thirty Years' War]] (1618–1648), with the smaller established Protestant states facing the aggression of the larger Catholic empires. On assuming the throne, James made peace with Catholic Spain, and made it his policy to marry his son to the Spanish Infanta (princess) [[Maria Anna of Spain|Maria Anna]] in the "[[Spanish Match]]". The marriage of James' daughter Princess [[Elizabeth of Bohemia|Elizabeth]] to [[Frederick V, Elector Palatine]] on 14 February 1613 was more than the social event of the era; the couple's union had important political and military implications. Across Europe, the German princes were banding together in the [[Protestant Union]], headquartered in [[Heidelberg]], the capital of the [[Electoral Palatinate]]. King James calculated that his daughter's marriage would give him diplomatic leverage among the Protestants. He thus planned to have a foot in both camps and be able to broker peaceful settlements. In his naïveté, he did not realise that both sides were playing him as a tool for their own goal of achieving the destruction of the other side.{{attribution needed|date=January 2023}} Spain's ambassador [[Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, 1st Count of Gondomar]] knew how to manipulate the king. The Catholics in Spain, as well as the Emperor [[Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor|Ferdinand II]], the [[Vienna]]-based leader of the Habsburgs and head of the [[Holy Roman Empire]], were both heavily influenced by the Catholic [[Counter-Reformation]]. They had the goal of expelling Protestantism from their domains.<ref>W. B. Patterson, "King James I and the Protestant cause in the crisis of 1618–22." ''Studies in Church History'' 18 (1982): 319–334.</ref>

Lord Buckingham in the 1620s wanted an alliance with Spain.<ref>Godfrey Davies, ''The Early Stuarts: 1603–1660'' (1959), pp 47–67</ref> Buckingham took Charles with him to Spain to woo the Infanta in 1623. However, Spain's terms were that James must drop Britain's anti-Catholic intolerance or there would be no marriage. Buckingham and Charles were humiliated and Buckingham became the leader of the widespread British demand for a war against Spain. Meanwhile, the Protestant princes looked to Britain, since it was the strongest of all the Protestant countries, to provide them with military support for their cause. James' son-in-law and daughter became king and queen of Bohemia, an event which outraged Vienna. The Thirty Years' War began, as the Habsburg Emperor ousted the new king and queen of the [[Kingdom of Bohemia]], and massacred their followers. The Catholic [[Duchy of Bavaria]] then invaded the [[Electoral Palatinate]], and James's son-in-law begged for James's military intervention. James finally realised that his policies had backfired and refused these pleas. He successfully kept Britain out of the European-wide war that proved so heavily devastating for three decades. James's backup plan was to marry his son Charles to a French Catholic princess, who would bring a handsome dowry. Parliament and the British people were strongly opposed to any Catholic marriage, were demanding immediate war with Spain, and strongly favoured the Protestant cause in Europe. James had alienated both elite and popular opinion in Britain, and Parliament was cutting back its financing. Historians credit James for pulling back from a major war at the last minute, and keeping Britain in peace.<ref>Jonathan Scott, ''England's Troubles: 17th-century English Political Instability in European Context'' (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp 98–101</ref>

Line 218 ⟶ 221:

===Anglo-Dutch Wars===

[[File:Battle of Scheveningen (Slag bij Ter Heijde)(Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten).jpg|thumb|The [[Battle of Scheveningen]] in 1653 was the final battle of the [[First Anglo-Dutch War]].]]

The [[Anglo-Dutch Wars]] were a series of three wars which took place between the English and the Dutch from 1652 to 1674. The causes included political disputes and increasing competition from merchant shipping. Religion was not a factor, since both sides were Protestant.<ref>Steven C. A. Pincus, ''Protestantism and Patriotism: Ideologies and the Making of English Foreign Policy, 1650–1668'' (1996)</ref> The British in the [[First Anglo-Dutch War]] (1652–54) had the naval advantage with larger numbers of more powerful "[[Ship of the line|ships of the line]]" which were well suited to the naval tactics of the era. The British also captured numerous Dutch merchant ships.

In the [[Second Anglo-Dutch War]] (1665–67) Dutch naval victories followed. This second war cost London ten times more than it had planned on, and the king sued for peace in 1667 with the [[Treaty of Breda (1667)|Treaty of Breda]]. It ended the fights over "[[mercantilism]]" (that is, the use of force to protect and expand national trade, industry, and shipping.) Meanwhile, the French were building up fleets that threatened both the Netherlands and Great Britain.

In the [[Third Anglo-Dutch War]] (1672–74), the British counted on a new alliance with France but the outnumbered Dutch outsailed both of them, and King Charles II ran short of money and political support. The Dutch gained domination of sea trading routes until 1713. The British gained the thriving colony of [[New Netherland]], which was renamed as the [[Province of New York]].<ref>James Rees Jones, ''The Anglo-Dutch wars of the seventeenth century'' (1996) [https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0582056306 online]</ref><ref>Gijs Rommelse, "The role of mercantilism in Anglo‐Dutch political relations, 1650–74." ''Economic History Review'' 63#3 (2010): 591–611.</ref>

==Timeline==

Line 307 ⟶ 314:

|align=center

|footer=

|File:Battle of Marston Moor JBarker1644 by John Barker.jpgpng

|alt1=The battle of Marston Moor, the English civil war.

|[[Battle of Marston Moor]]

Line 322 ⟶ 329:

==Further reading==

* Braddick, Michael J. ''The Nerves of State: Taxation and the Financing of the English State, 1558-1714'' (Manchester University Press, 1996).

* Bucholz, Robert, and Newton Key. ''Early modernModern England 1485–1714: A narrativeNarrative historyHistory'' (2009); university textbook.

* Burke, Peter "Popular cultureCulture in seventeenthSeventeenth-century London." ''The London Journal'' 3.2 (1977): 143–162. [http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1179/ldn.1977.3.2.143 online]

* Campbell, Mildred. ''English yeomanYeoman underUnder Elizabeth and the earlyEarly Stuarts'' (1942), rich coverage of rural life

* Clark, George, ''The Later Stuarts, 1660–1714'' (Oxford History of England) (2nd ed. 1956), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

* Coward, Barry, and Peter Gaunt. ''The Stuart Age: England, 1603–1714'' (5th ed 2017) [https://www.amazon.com/Stuart-Age-England-1603-1714/dp/113894954X/ref=mt_hardcover?_encoding=UTF8&me= new introduction]; a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

Line 331 ⟶ 339:

* Fritze, Ronald H. and William B. Robison, eds. ''Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689'' (1996), 630pp; 300 short essays by experts emphasis on politics, religion, and historiography [https://www.amazon.com/Historical-Dictionary-Stuart-England-1603-1689/dp/0313283915/ excerpt]

* {{cite book|author=Holmes, Geoffrey|title=British Politics in the Age of Anne|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5GOtAwAAQBAJ|year=1987|publisher=A&C Black|page=643pp|isbn=9780907628743}}

* Hoppit, Julian. ''A landLand of libertyLiberty?: England 1689–1727'' (Oxford UP, 2000) (The New Oxford History of England), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

* Kenyon, J.P. ''Stuart England'' (Penguin, 1985), survey

* Kishlansky, Mark A. ''A Monarchy Transformed: Britain, 1603–1714'' (Penguin History of Britain) (1997), standard scholarly survey; [https://www.amazon.com/dp/0140148272/ excerpt and text search]

* Kishlansky, Mark A. and John Morrill. "Charles I (1600–1649)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004; online edn, Oct 2008) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5143, accessed 22 Aug 2017] doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5143

* Lipson, Ephraim. ''The economicEconomic historyHistory of England: vol 2: The Age of Mercantilism'' (7th ed. 1964)

* Miller, John. ''The Stuarts'' (2004)

* Miller, John. ''The restorationRestoration and the England of Charles II'' (2014).

* Morrill, John. ''Stuart Britain: A Very Short Introduction'' (2005) [https://www.amazon.com/Stuart-Britain-Very-Short-Introduction/dp/0192854003/ excerpt and text search]; 100pp

* Morrill, John, ed. ''The Oxford illustrated historyHistory of Tudor & Stuart Britain'' (1996) [https://archive.org/details/oxfordillustrate00john online], a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

* Mulligan, William, and Brendan Simms, eds. ''The Primacy of Foreign Policy in British History, 1660–2000'' (2011) pp 15–64.

* Murray, Catriona. ''Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity'' (Routledge, 2017).

* Notestein, Wallace. ''English peoplePeople on the eveEve of colonizationColonization, 1603–1630'' (1954). scholarly study of occupations and roles

* O'Brien, Patrick K. "The Political Economy of British Taxation, 1660‐1815", in ''Economic History Review'' (1988) 41#1 pp: 1–32. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2597330 in JSTOR]

* Ogg, David. ''England in the Reign of Charles II'' (2 vol 1934), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

* Ogg, David. ''England in the Reigns of James II and William III'' (1955), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

Line 351 ⟶ 360:

* Sharp, David. ''England in Crisis 1640–60'' (2000), textbook

* Sharp, David. ''Oliver Cromwell'' (2003); textbook

* Sharpe, Kevin. ''The personalPersonal ruleRule of Charles I'' (Yale UP, 1992).

* Sharpe, Kevin, and Peter Lake, eds. ''Culture and politicsPolitics in earlyEarly Stuart England'' (1993)

* Thurley, Simon. ''Palaces of Revolution: Life, Death and Art at the Stuart Court'' (2021)

* Traill, H. D. and J.S. Mann, eds. ''Social England; a record of the progress of the people in religion, laws, learning, arts, industry, commerce, science, literature and manners, from the earliest times to the present day'' (1903) short essays by experts; illustrated' 946pp. [https://archive.org/details/socialenglandrec04trai online]

* Wilson, Charles. ''England's apprenticeshipApprenticeship, 1603–1763'' (1967), comprehensive economic and business history.

* Woolrych, Austin. ''Britain in Revolution: 1625–1660'' (2004), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

* Wroughton, John. ed. ''The Routledge Companion to the Stuart Age, 1603–1714'' (2006) [https://books.google.com/books?id=bi0zMV4hTTQC excerpt and text search]

Line 361 ⟶ 371:

* Baxter, Steven B. "The Later Stuarts: 1660–1714," in Richard Schlatter, ed., ''Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing since 1966'' (Rutgers UP, 1984), pp 141–66

* Braddick, Michael J., ed. ''The Oxford Handbook of the English Revolution'' (Oxford UP, 2015). 645pp 33 essays by experts on specialised topics; emphasis on historiography

* Burgess, Glenn. "On revisionismRevisionism: anAn analysisAnalysis of earlyEarly Stuart historiographyHistoriography in the 1970s and 1980s." ''Historical Journal'' (1990) 33#3 pp: 609–27. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2639733 online]

* Cressy, David. "The Blindness of Charles I." ''Huntington Library Quarterly'' 78.4 (2015): 637–656. [https://muse.jhu.edu/article/610820/summary excerpt]

* Harris, Tim. "Revisiting the Causes of the English Civil War." ''Huntington Library Quarterly'' 78.4 (2015): 615–635. [https://muse.jhu.edu/article/610819/summary excerpt]

Line 379 ⟶ 389:

* Browning, A. ed. ''English Historical Documents 1660–1714'' (1953)

* Coward, Barry, and Peter Gaunt, eds. ''English Historical Documents, 1603–1660'' (2011)

* Key, Newton, and Robert O. Bucholz, eds. ''Sources and debatesDebates in English historyHistory, 1485–1714'' (2009).

* Kenyon, J.P. ed. ''The Stuart Constitution, 1603–1688: Documents and Commentary'' (1986).

* Lindley, Keith, ed. ''The English Civil War and Revolution: A Sourcebook'' (Routledge, 2013). 201pp

* Stater, Victor, ed. ''The Political History of Tudor and Stuart England: A Sourcebook'' (Routledge, 2002) [https://www.questia.com/library/108130578/the-political-history-of-tudor-and-stuart-england online]

* Williams, E.N., ed., ''The Eighteenth-century Constitution 1688–1815: Documents and Commentary'' (1960), 464pp.

Line 407 ⟶ 417:

{{end}}

{{Pictish and Scottish Monarchs}}

{{English and British monarchs}}

{{Kingdom of Scotland}}

{{Kingdom of England}}