Watts riots: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Line 3:

{{Infobox civil conflict

| title = Watts riots

| partof = the [[Ghetto riots|Ghetto riots of the 1960s]]

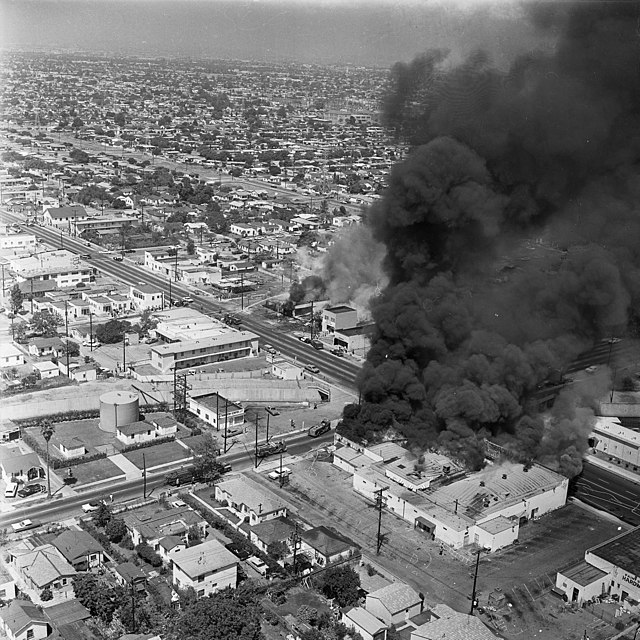

| image = [[File:WattsriotsWatts Riots -burningbuildings-loc buildings on fire on Avalon Blvd.jpg|300px]]

| caption = BurningTwo buildings duringon thefire riotson [[Avalon Boulevard]]

| date = August 11–16, 1965

| place = [[Watts, Los Angeles]]

| causes =

| status =

| goals = To end alleged mistreatment by the police and to end discrimination in housing, employment, and schooling systems

| methods = Widespread rioting, looting, assault, arson, protests, firefights, and property damage

| side1 =

| side2 =

| side3 =

| leadfigures1 =

| leadfigures2 =

| leadfigures3 =

| howmany1 =

| howmany2 =

| howmany3 =

| fatalities = 34

| injuries = 1,032

| arrests = 3,438

| notes =

}}

{{Campaignbox Ghetto riots}}

The '''Watts riots''', sometimes referred to as the '''Watts Rebellion''' or '''Watts Uprising''',<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/watts-rebellion-los-angeles|title=Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles) {{!}} The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute|website=kinginstitute.stanford.edu|language=en|access-date=2018-10-22|date=June 12, 2017}}</ref> took place in the [[Watts, Los Angeles|Watts]] neighborhood and its surrounding areas of [[Los Angeles]] from August 11 to 16, 1965. The riots were motivated by anger at the racist and abusive practices of the [[Los Angeles Police Department]], as well as grievances over employment discrimination, residential segregation, and poverty in L.A.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Felker-Kantor |first=Max |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=C0dwDwAAQBAJ |title=Policing Los Angeles: Race, Resistance, and the Rise of the LAPD |date=2018 |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |isbn=978-1-4696-4684-8 |language=en}}</ref>

On August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old [[African-American]] man, was pulled over for [[drunkendrunk driving]].<ref name="traffic2">{{Cite news|author=Queally|first=James|date=2015-07-29|title=Watts Riots: Traffic stop was the spark that ignited days of destruction in L.A.|newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]|url=http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-watts-riots-explainer-20150715-htmlstory.html|access-date=May 31, 2020}}</ref><ref name="tribunedigital-orlandosentinel">{{Cite news|url=httphttps://articleswww.orlandosentinel.com/1990-/08-/05/news/9008031131_1_fryehow-riotslegacy-inof-americanthe-rightswatts-riot-consumed-leadersruined-mans-life/2|title=How Legacy Of The Watts Riot Consumed, Ruined Man's Life|work=Orlando Sentinel|access-date=2018-03-02|language=en|archive-date=July 24, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180724062907/http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1990-08-05/news/9008031131_1_frye-riots-in-american-rights-leaders/2|url-status=deadlive}}</ref><ref name="articles.latimes.comLos Angeles Times">Dawsey, Darrell (August 19, 1990). [httphttps://articleswww.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-08-19/local/-me-2790_1_chp2790-officerstory.html "To CHP Officer Who Sparked Riots, It Was Just Another Arrest"]. ''[[Los Angeles Times]]''.</ref> After he failed a field sobriety test, officers attempted to arrest him. Marquette resisted arrest, with assistance from his mother, Rena Frye; a physical confrontation ensued in which Marquette was struck in the face with a baton. Meanwhile, a crowd of onlookers had gathered.<ref name="traffic2" /> Rumors spread that the police had kicked a pregnant woman who was present at the scene. Six days of civil unrest followed, motivated in part by allegations of police abuse.<ref name="tribunedigital-orlandosentinel" /> Nearly 14,000 members of the [[California Army National Guard]]<ref>{{Cite web|date=2017-06-12|title=Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles)|url=https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/watts-rebellion-los-angeles|access-date=2020-06-06|website=The Martin Luther King Jr., Research and Education Institute|language=en}}</ref> helped suppress the disturbance, which resulted in 34 deaths,<ref name="Hinton2">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ATS6CwAAQBAJ&q=Turn+left+or+get+shot&pg=PA69|title=From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America|last1=Hinton|first1=Elizabeth|date=2016|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=9780674737235|pages=68–72}}</ref> as well as over $40 million in property damage.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Joshua |first1=Bloom |last2=Martin |first2=Waldo |title=Black Against Empire: The History And Politics Of The Black Panther Party| title-link = Black Against Empire |date=2016 |publisher=University of California Press |page=30}}</ref><ref name="Szymanski">{{cite news|last=Szymanski|first=Michael|title=How Legacy of the Watts Riot Consumed, Ruined Man's Life|newspaper=Orlando Sentinel|date=August 5, 1990|url=httphttps://articleswww.orlandosentinel.com/1990-/08-/05/news/9008031131_1_fryehow-riotslegacy-inof-americanthe-rightswatts-leadersriot-consumed-ruined-mans-life/|access-date=22 June 2013|archive-date=December 6, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131206012123/http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1990-08-05/news/9008031131_1_frye-riots-in-american-rights-leaders|url-status=deadlive}}</ref> It was the city's worst unrest until the [[Rodney King riots]] of 1992.

==Background==

{{Original research section|reason=Most of the sources used make no connection of their material with the Watts riots, which violates [[WP:NOR]]. (See Talk.)|date=January 2024}}

In the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]] of 1915–1940, major populations of [[African American]]s moved to [[Northeastern United States|Northeastern]] and [[Midwestern United States|Midwestern]] cities such as [[Detroit]], [[Chicago]], [[St. Louis]], [[Cincinnati]], [[Philadelphia]], [[Boston]], and [[New York City]] to pursue jobs in newly established manufacturing industries; to cement better educational and social opportunities; and to flee [[racial segregation in the United States|racial segregation]], [[Jim Crow laws]], violence and [[Racism|racial bigotry]] in the [[Southern United States|Southern states]]. This wave of migration largely bypassed Los Angeles.<ref>{{Cite web|last=McReynolds|first=Devon|date=February 14, 2016|title=Photos: Black Los Angeles During The First 'Great Migration'|url=https://laist.com/2016/02/14/first_great_migration_photos.php|access-date=2020-11-13|website=LAist}}</ref>

Line 37 ⟶ 38:

===Residential segregation===

Los Angeles had racially restrictive covenants that [[redlining|prevented specific minorities from renting and buying]] property in certain areas, even long [[Shelley v. Kraemer|after the courts ruled such practices illegal in 1948]] and the [[Civil Rights Act of 1964]] was passed. At the beginning of the 20th century, Los Angeles was geographically divided by ethnicity, as demographics were being altered by the rapid migration from the Philippines ([[Unincorporated territories of the United States|U.S. unincorporated territory]] at the time) and immigration from Mexico, Japan, Korea, and Southern and Eastern Europe. In the 1910s, the city was already 80% covered by [[Restrictive covenant|racially restrictive covenants]] in real estate.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Taylor|first1=Dorceta|author-link=Dorceta Taylor|title=Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility|date=2014|publisher=NYU Press|isbn=9781479861620|page=202|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TFuOAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA202}}</ref> By the 1940s, 95% of Los Angeles and southern California housing was off-limits to certain minorities.<ref name=bernstein/><ref>{{cite book|author1=Michael Dear |author2=H. Eric Schockman |author3=Greg Hise |name-list-style=amp |title=Rethinking Los Angeles|date=1996|publisher=SAGESage|isbn=9780803972872|page=40|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1oC_qZREzNIC&pg=PA40}}</ref> Minorities who had served in World War II or worked in L.A.'s defense industries returned to face increasing patterns of [[Housing Segregation|discrimination in housing]]. In addition, they found themselves excluded from the suburbs and restricted to housing in [[East Los Angeles, California|East]] or [[South Los Angeles]], which includes the [[Watts, Los Angeles|Watts]] neighborhood and [[Compton, California|Compton]]. Such real-estate practices severely restricted educational and economic opportunities available to the minority community.<ref name=bernstein>{{cite book|last1=Bernstein|first1=Shana|title=Bridges of Reform: Interracial Civil Rights Activism in Twentieth-Century Los Angeles|date=2010|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780199715893|pages=107–109|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PkyRXd-jgnEC&pg=PA107}}</ref>

Following the US entry into World War II after the [[attack on Pearl Harbor]], the federal government [[Internment of Japanese Americans|removed and interned]] 70,000 Japanese-Americans from Los Angeles, leaving empty spaces in predominantly Japanese-owned areas. This further bolstered the migration of black residents into the city during the Second Great Migration to occupy the vacated spaces, such as [[Little Tokyo, Los Angeles|Little Tokyo]]. As a result, housing in South Los Angeles became increasingly scarce, overwhelming the already established communities and providing opportunities for real estate developers. Davenport Builders, for example, was a large developer who responded to the demand, with an eye on undeveloped land in Compton. What was originally a mostly white neighborhood in the 1940s increasingly became an African-American, middle-class dream in which blue-collar laborers could enjoy suburbia away from the slums.<ref name=bernstein/>

Line 43 ⟶ 44:

In the post-World War II era, suburbs in the Los Angeles area grew explosively as black residents also wanted to live in peaceful white neighborhoods. In a thinly-veiled attempt to sustain their way of life and maintain the general peace and prosperity, most of these suburbs barred black people, using a variety of methods. White middle-class people in neighborhoods bordering black districts moved en masse to the suburbs, where newer housing was available. The spread of African Americans throughout urban Los Angeles was achieved in large part through [[blockbusting]], a technique whereby real estate speculators would buy a home on an all-white street, sell or rent it to a black family, and then buy up the remaining homes from Caucasians at cut-rate prices, then sell them to housing-hungry black families at hefty profits.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Gaspaire|first=Brent|date=2013-01-07|title=Blockbusting|url=https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/blockbusting/|access-date=2020-11-13|language=en-US}}</ref>

The Rumford Fair Housing Act, designed to remedy residential segregation, was overturned by [[California Proposition 14 (1964)|Proposition 14]] in 1964, which was sponsored by the California real estate industry, and supported by a majority of white voters. Psychiatrist and civil rights activist [[Alvin Poussaint]] considered Proposition 14 to be one of the causes of black rebellion in Watts.<ref>{{cite book |last=Theoharis, |first=Jeanne (|year=2006) |editor-last=Joseph |editor-first=Peniel E. [|title=The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights–Black Power Era |publisher=Routledge |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rEG42f9T77IC&dq=ALABAMA+ON+AVALON%2C+theoharis&pg=PA28PA46 ''The|pages=46–48 Black|chapter=Chapter Power Movement1: Rethinking"Alabama theon CivilAvalon" Rights-BlackRethinking Powerthe Era''].Watts (NewUprising York:and Routledge),the p.Character 47-49.of ArchivedBlack atProtest Googlein Books.Los RetrievedAngeles February|isbn=9780415945967 4|access-date=January 9, 2016.2024}}</ref>

In 1950, [[William H. Parker (police officer)|William H. Parker]] was appointed and sworn in as Los Angeles Chief of Police. After a major scandal called [[Bloody Christmas (1951)|Bloody Christmas of 1951]], Parker pushed for more independence from political pressures that would enable him to create a more professionalized police force. The public supported him and voted for charter changes that isolated the police department from the rest of the city government. In the 1960s, the LAPD was promoted{{by whom|date=June 2020}} as one of the best police forces in the world.{{Citation needed|reason=Needs citations for claims|date=June 2020}}

Despite its reform and having a professionalized, military-like police force, William Parker's LAPD faced repeated criticism from the city's Latino and black residents for [[police brutality]]—resulting{{snd}}resulting from his recruiting of officers from the South with strong anti-black and anti-Latino attitudes. Chief Parker coined the term "[[The Thin Blue Line (emblem)|thin blue line]]", representing the police as holding down pervasive crime.<ref>{{cite web |last=Shaw |first=David |title=Chief Parker Molded LAPD Image-- – Then Came the '60s : Police: Press treated officers as heroes until social upheaval prompted skepticism and confrontation. |newspaper=Los Angeles Times |date= May 25, 2014 |url=httphttps://articleswww.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-05-25/news/-mn-236_1_police236-brutalitystory.html |access-date=21 September 2014 }}</ref>

Resentment of such longstanding racial injustices is cited as reason why Watts' African-American population exploded on August 11, 1965, in what would become the Watts Riots.<ref>[http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aaw/watts-rebellion-august-1965 Watts Riots (August 1965) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed]. The Black Past (August 11, 1965).</ref>

==Inciting incident==

On the evening of Wednesday, August 11, 1965, 21-year-old Marquette Frye, an African-American man driving his mother's 1955 Buick while drunk, was pulled over by [[California Highway Patrol]] rookie motorcycle officer Lee Minikus for alleged reckless driving.<ref name="articles.latimes.comLos Angeles Times"/> After Frye failed a field sobriety test, Minikus placed him under arrest and radioed for his vehicle to be impounded.<ref>Cohen, Jerry; Murphy, William S. (July 15, 1966). [https://books.google.com/books?id=olUEAAAAMBAJ&dq=marquette+frye+reckless&pg=PA36 "Burn, Baby, Burn!"] ''[[Life (magazine)|Life]]''. Archived at [[Google Books]]. Retrieved February 4, 2016.</ref> Marquette's brother, Ronald, a passenger in the vehicle, walked to their house nearby, bringing their mother, Rena Price, back with him to the scene of the arrest.

When Rena Price reached the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street that evening, she scolded Frye about drinking and driving as he recalled in a 1985 interview with the ''Orlando Sentinel''.<ref>{{cite news|last=Szymanski|first=Michael|title=How Legacy of the Watts Riot Consumed, Ruined Man's Life|newspaper=Orlando Sentinel|date=August 5, 1990|url=httphttps://articleswww.orlandosentinel.com/1990-/08-/05/news/9008031131_1_fryehow-riotslegacy-inof-americanthe-rightswatts-riot-consumed-leadersruined-mans-life/|access-date=22 June 2013 |archive-date=6 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131206012123/http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/1990-08-05/news/9008031131_1_frye-riots-in-american-rights-leaders |url-status=live }}</ref> However, the situation quickly escalated: someone shoved Price, Frye was struck, Price jumped an officer, and another officer pulled out a shotgun. Backup police officers attempted to arrest Frye by using physical force to subdue him. After community members reported that police had roughed up Frye and shared a rumor they had kicked a pregnant woman, angry mobs formed.<ref>{{cite news|last=Dawsey|first=Darrell|title=To CHP Officer Who Sparked Riots, It Was Just Another Arrest|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=August 19, 1990|url=httphttps://articleswww.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-08-19/local/-me-2790_1_chp2790-officerstory.html|access-date=November 23, 2011}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite news|last=Woo|first=Elaine|title=Rena Price dies at 97; her and son's arrests sparked Watts riots|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=June 22, 2013|url=http://www.latimes.com/news/obituaries/la-me-rena-price-20130623,0,1084258.story|access-date=22 June 2013}}</ref> As the situation intensified, growing crowds of local residents watching the exchange began yelling and throwing objects at the police officers.<ref name=":0">Abu-Lughod, Janet L. ''Race, Space, and Riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.</ref>{{pagePage neededreference|datepage=August 2020205}} Frye's mother and brother fought with the officers and eventually were arrested along with Marquette Frye.<ref name=encycl>{{cite book|last=Walker|first=Yvette|title=Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2008}}</ref>{{page needed|date=August 2020}}<ref name="Alonso, Alex A.">{{cite book |last=Alonso |first=Alex A. |date=1998 |title=Rebuilding Los Angeles: A Lesson of Community Reconstruction |publisher=[[University of Southern California]] |location=Los Angeles |url=http://www.streetgangs.com/academic/1998.Alonso-RLAreport-final-001.pdf }}{{Dead link|date=March 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref>{{page needed|date=August 2020}}{{dead link|date=August 2020}}<ref name="Szymanski"/>{{Failed verification|date=April 2024}}<ref name=":0" />{{Page reference|page=207}}

After the arrests of Price and her sons, the Frye brothers, the crowd continued to grow along Avalon Boulevard. Police came to the scene to break up the crowd several times that night, but were attacked when people threw rocks and chunks of concrete.<ref name="revolts">{{cite book | chapter=Watts Riots (1965) | title=Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History, Volume 3 | publisher=ABC-CLIO | last=Barnhill | first=John H. | editor=Danver, Steven L. | year=2011}}</ref> A {{convert|46|sqmi|adj=on}} swath of Los Angeles was transformed into a combat zone during the ensuing six days.<ref name="auto"/>

==Riot begins==

Line 64 ⟶ 65:

After a night of increasing unrest, police and local black community leaders held a community meeting on Thursday, August 12, to discuss an action plan and to urge calm. The meeting failed. Later that day, Chief Parker called for the assistance of the [[California Army National Guard]].<ref name=mccone>{{cite web|title=Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning?|url=http://www.usc.edu/libraries/archives/cityinstress/mccone/contents.html|access-date=January 3, 2012|archive-date=May 14, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120514142049/http://www.usc.edu/libraries/archives/cityinstress/mccone/contents.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> Chief Parker believed the riots resembled an insurgency, compared it to fighting the [[Viet Cong]], and decreed a "[[paramilitary]]" response to the disorder. Governor [[Pat Brown]] declared that law enforcement was confronting "[[guerrilla]]s fighting with gangsters".<ref name="Hinton2"/>

The rioting intensified, and on Friday, August 13, about 2,300 National Guardsmen joined the police in trying to maintain order on the streets. Sergeant Ben Dunn said: "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=htrYAgAAQBAJ&q=Sergeant+Ben+Dunn+LAPD+Watt+riots&pg=PA135|title=The Revolt Against the Masses: How Liberalism Has Undermined the Middle Class|last=Siegel|first=Fred|date=2014-01-28|publisher=Encounter Books|isbn=9781594036989|language=en}}</ref>{{page needed|date=August 2020}}<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MlQEDQAAQBAJ&q=Sergeant+Ben+Dunn+LAPD+Watt+riots&pg=PA156|title=Shall We Wake the President?: Two Centuries of Disaster Management from the Oval Office|last=Troy|first=Tevi|publisher=Rowman and Littlefield|year=2016|isbn=9781493024650|pages=156}}</ref> The first riot-related death occurred on the night of August 13, when a black civilian was killed in the crossfire during a [[shootout]] between the police and rioters. Over the next few days, rioting had then spread throughout other areas, including [[Pasadena, California|Pasadena]], [[Pacoima, Los Angeles|Pacoima]], [[Monrovia, California|Monrovia]], [[Long Beach, California|Long Beach]], and even as far as [[San Diego]], although they were very minor in comparison to Watts. About 200 Guardsmen and the LAPD were sent to assist the [[Long Beach Police Department (California)|Long Beach Police Department]] (LBPD) in controlling the unruly crowd.

By nightfall on Saturday, 16,000 law enforcement personnel had been mobilized and patrolled the city.<ref name="Hinton2"/> Blockades were established, and warning signs were posted throughout the riot zones threatening the use of [[deadly force]] (one sign warned residents to "Turn left or get shot"). Angered over the police response, residents of Watts engaged in a full-scale battle against the [[first responder]]s. Rioters tore up sidewalks and bricks to hurl at Guardsmen and police, and to smash their vehicles.<ref name="Hinton2"/> Those actively participating in the riots started physical fights with police and blocked [[Los Angeles Fire Department]] (LAFD) firefighters from using fire hoses on protesters and burning buildings. [[Arson]] and [[looting]] were largely confined to local white-owned stores and businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to low wages and high prices for local workers.<ref name="Oberschall">{{Cite journal | last1 = Oberschall | first1 = Anthony | year = 1968 | title = The Los Angeles Riot of August 1965 | journal = Social Problems | volume = 15 | issue = 3 | pages = 322–341 | jstor = 799788 | doi=10.2307/799788}}</ref>

Line 70 ⟶ 71:

To quell the riots, Chief Parker initiated a policy of [[mass arrest]].<ref name="Hinton2"/> Following the deployment of National Guardsmen, a curfew was declared for a vast region of [[South Los Angeles|South Central Los Angeles]].<ref>{{cite web|title=A Report Concerning the California National Guard's Part in Suppressing the Los Angeles Riot, August 1965|url=http://www.militarymuseum.org/watts.pdf}}</ref> In addition to the Guardsmen, 934 LAPD officers and 718 officers from the [[Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department]] (LASD) were deployed during the rioting.<ref name=mccone/> Watts and all black-majority areas in Los Angeles were put under the curfew. All residents outside of their homes in the affected areas after 8:00{{spaces}}p.m. were subject to arrest. Eventually, nearly 3,500 people were arrested, primarily for curfew violations. By the morning of Sunday, August 15, the riots had largely been quelled.<ref name="Hinton2"/>

Over the course of six days, between 31,000 and 35,000 adults participated in the riots. Around 70,000 people were "sympathetic, but not active."<ref name=revolts/> Over the six days, there were 34 deaths,<ref name=RareNewspapers>[http://www.rarenewspapers.com/view/609877 "The Watts Riots of 1965, in a Los Angeles newspaper... "]. Timothy Hughes: Rare & Early Newspapers. Retrieved February 4, 2016.</ref><ref>Reitman, Valerie; Landsberg, Mitchell (August 11, 2005). [httphttps://articleswww.latimes.com/2005/aug/11/localnews/la-me-watts11aug11-story.html "Watts Riots, 40 Years Later"]. ''Los Angeles Times''.</ref> 1,032 injuries,<ref name=RareNewspapers/><ref>[http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/watts-riot-begins "Watts Riot begins -– August 11, 1965"]. This Day in History. [[History (U.S. TV channel)|History]]. Retrieved February 3, 2016.</ref> 3,438 arrests,<ref name=RareNewspapers/><ref>[http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8t43x7s/entire_text/ "Finding aid for the Watts Riots records 0084"]. [[Online Archive of California]]. Retrieved February 3, 2016.</ref> and over $40 million in property damage from 769 buildings and businesses damaged and looted and 208 buildings completely destroyed, including 14 damaged public buildings and 1 public building completely destroyed.<ref name=RareNewspapers/><ref>{{Cite news |date=August 11, 2015 |title=Inside the Watts curfew zone |work=[[Los Angeles Times]] |url=https://graphics.latimes.com/watts-riots-1965-map/ |access-date=May 20, 2023}}</ref> Many white Americans were fearful of the breakdown of social order in Watts, especially since white motorists were being pulled over by rioters in nearby areas and assaulted.<ref>Queally, James (July 29, 2015). [http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-watts-riots-explainer-20150715-htmlstory.html "Watts Riots: Traffic stop was the spark that ignited days of destruction in L.A."], ''Los Angeles Times''.</ref> Many in the black community, however, believed the rioters were taking part in an "uprising against an oppressive system."<ref name=revolts/> In a 1966 essay, black civil rights activist [[Bayard Rustin]] wrote:

<blockquote>The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own [[:wikt:masochism|masochism]] and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.<ref name=rustin>{{cite news|last=Rustin|first=Bayard|title=The Watts|url=http://www.commentarymagazine.com/article/the-watts/|access-date=January 3, 2012|newspaper=Commentary Magazine|date=March 1966}}</ref></blockquote>

Despite allegations that "criminal elements" were responsible for the riots, the vast majority of those arrested had no prior criminal record.<ref name="Hinton2"/> Three sworn personnel were killed in the riots: ana LAFDLos Angeles Fire Department firefighter was struck when a wall of a fire-weakened structure fell on him while fighting fires in a store,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.lafire.com/lastalarm_file/1965-0814_Tilson/WarrenTilson.htm|title=Fireman Warren E. Tilson, Los Angeles Fire Department|publisher=Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive}}</ref> ana LASDLos Angeles County Sheriff's deputy was accidentally shot by another deputy while in a struggle with rioters,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.odmp.org/officer/8316-deputy-sheriff-ronald-e-ludlow|title=Deputy Sheriff Ronald E. Ludlow|publisher=[[Officer Down Memorial Page]]}}</ref> and ana LBPDLong Beach Police Department officer was shot by another police officer during a scuffle with rioters.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.odmp.org/officer/8032-police-officer-richard-r-lefebvre|title=Police Officer Richard R. LeFebvre|publisher=[[Officer Down Memorial Page]]}}</ref> 23 out of the 34 people killed in the riots were shot by LAPD officers or National Guardsmen.<ref>{{Cite magazine|last=Jerkins|first=Morgan|date=August 3, 2020|title=A Haunting Story Behind the 1965 Watts Riots|url=https://time.com/5873228/watts-riots-memory/|access-date=2020-11-14|magazine=Time}}</ref>

==After the riots==

Line 86 ⟶ 87:

After the Watts Riots, white families left surrounding nearby suburbs like Compton, Huntington Park, and South Gate in large numbers.<ref>{{Cite news|title=On Race, Housing, and Confronting History|url=https://www.thedowneypatriot.com/articles/on-race-housing-and-confronting-history|access-date=August 23, 2020 |newspaper=The Downey Patriot |first=Aron |last=Ramirez |date=July 10, 2019}}</ref> Although the unrest did not reach these suburbs during the riots, many white residents in Huntington Park, for instance, left the area.<ref>{{Cite news|last1= Holguin |first1=Rick |first2=George |last2=Ramos |date=April 7, 1990 |title=Cultures Follow Separate Paths in Huntington Park |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-07-mn-591-story.html|access-date=August 23, 2020 |newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]}}</ref>

With so much destruction of residential properties after the Watts Riots, black families began to relocate in other cities that had established black neighborhoods. One of these was the city of [[Pomona, California|Pomona, CA]]. Ironically, theThe arrival of so many black families to Pomona caused [[White flight]] to take place there and saw many of those white families move to neighboring cities in the [[Pomona Valley]].<ref>{{Cite news |date=2015-08-08 |title=Watts riots: Inland Valley African-Americans faced same problems |url=https://www.dailybulletin.com/general-news/20150808/watts-riots-inland-valley-african-americans-faced-same-problems |access-date=2022-12-05 |work=Daily Bulletin |language=en-US}}</ref>

=== McCone Commission ===

A commission under Governor [[Pat Brown]] investigated the riots, known as the McCone Commission, and headed by former [[Central Intelligence Agency|CIA]] director [[John A. McCone]]. Other committee members included [[Warren Christopher]], a Los Angeles attorney who would be the committee's vice chairman, Earl C. Broady, Los Angeles Superior Court judge; Asa V. Call, former president of the State Chamber of Commerce; Rev. Charles Casassa, president of Loyola University of Los Angeles; the [[Westminster Presbyterian Church (Los Angeles)#Rev. Dr. James E. Jones|Rev. James E. Jones]] of Westminster Presbyterian Church and member of the Los Angeles Board of Education; Mrs. Robert G. Newmann, a League of Women Voters leader; and [[Sherman Mellinkoff|Dr. Sherman M. Mellinkoff]], dean of the School of Medicine at UCLA. The only two African American members were Jones and Broady.<ref>{{cite news |title=King and Yorty Feud Over Causes of Roiting in LA |url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/97743848 |access-date=3 July 2021 |work=Detroit Free Press at Newspapers.com |date=20 Aug 1965 |page=17 |language=en}}</ref>

The commission released a 101-page report on December 2, 1965, entitled ''Violence in the City—AnCity{{snd}}An End or a Beginning?: A Report by the Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965''.<ref>[http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15799coll115/id/119 ''Violence in the City—AnCity{{snd}}An End or a Beginning?: A Report by the Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965'']. [[University of Southern California]]. Retrieved August 21, 2014.</ref>

The McCone Commission identified the root causes of the riots to be high unemployment, poor schools, and related inferior living conditions that were endured by African Americans in Watts. Recommendations for addressing these problems included "emergency literacy and preschool programs, improved police-community ties, increased low-income housing, more job-training projects, upgraded health-care services, more efficient public transportation, and many more." Most of these recommendations were never implemented.<ref>{{cite news|last=Dawsey|first=Darrell|title=25 Years After the Watts Riots : McCone Commission's Recommendations Have Gone Unheeded|url=httphttps://articleswww.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-07-08/local/-me-455_1_watts455-riotsstory.html|access-date=November 22, 2011|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=July 8, 1990}}</ref>

=== Aftermath ===

{{expand section|date=February 2019}}

<!-- There should be more added here. The failure of the city to address these problems, and the slow pace of recovery, including continued discrimination by police department, contributed to later problems and riots, and to jury acquittal of OJ Simpson in the criminal murder case.-->

Marquette Frye was convicted of drunk driving, battery and malicious mischief. On February 18, 1966 he received a sentence of 90 days in county jail and three years' probation.<ref>https://www.newspapers.com/image/382248722/?terms=Marquette%20Frye&match=1 Los Angeles Times, 19 February 1966, p. 17</ref> He received another 90-day jail term after a jury convicted him of battery and disturbing the peace on May 18, 1966.<ref>https://www.newspapers.com/image/382248954/?terms=Marquette%20Frye&match=1 Los Angeles Times, 19 May 1966, p. 3</ref> Over the 10-year period following the riots he was arrested 34 times.<ref>https://www.newspapers.com/image/74401058/?terms=Marquette%20Frye&match=1 Progress Bulletin, 17 August 1975, p. 6</ref> He died of [[pneumonia]] on December 20, 1986, at age 42.<ref>{{cite news|title=Marquette Frye Dead; 'Man Who Began ///..Riot|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/25/obituaries/marquette-frye-dead-man-who-began-riot.html|newspaper=The New York Times|date=December 25, 1986|access-date=23 June 2013}}</ref> His mother, Rena Price, died on June 10, 2013, at age 97.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.presstelegram.com/general-news/20130623/rena-price-woman-whose-arrest-sparked-watts-riots-dies-at-97|title=Rena Price, woman whose arrest sparked Watts riots, dies at 97|date=June 23, 2013}}</ref> She never recovered the impounded 1955 Buick which her son had been driving because the storage fees exceeded the car's value.<ref>{{cite news|last=Woo|first=Elaine|title=Rena Price dies at 97; her and son's arrests sparked Watts riots|url=http://www.latimes.com/news/obituaries/la-me-rena-price-20130623,0,1084258.story|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=June 22, 2013|access-date=22 June 2013}}</ref> Motorcycle officer Lee Minikus died on October 19, 2013, at age 79.

==Cultural references==

Line 105 ⟶ 106:

* The [[Hughes brothers]] film ''[[Menace II Society]]'' (1993) opens with images taken from the riots of 1965. The entire film is set in Watts from the 1970s to the 1990s.

* [[Frank Zappa]] wrote a lyrical commentary inspired by the Watts riots, entitled "[[Trouble Every Day (song)|Trouble Every Day]]". It contains such lines as "Wednesday I watched the riot / Seen the cops out on the street / Watched 'em throwin' rocks and stuff /And chokin' in the heat". The song was released on his debut album ''[[Freak Out!]]'' (with the original [[The Mothers of Invention|Mothers of Invention]]), and later slightly rewritten as "More Trouble Every Day", available on ''[[Roxy and Elsewhere]]'' and ''[[The Best Band You Never Heard In Your Life]]''.

* [[Phil Ochs]]' 1965 song "In the Heat of the Summer", most famously recorded by [[Fifth Album|Judy Collins]], was a chronicle of the Watts Riots.

* [[Gil Scott-Heron]]'s song, ''[[The Revolution Will Not Be Televised]]'', directly references the Watts riots.

* [[Curt Gentry]]'s 1968 novel, ''[[The Last Days of the Late, Great State of California]]'', dissected the riots in detail in a fact-based semi-documentary tone.

* [[Joan Didion]]'s 1968 essay, "[[Slouching Towards Bethlehem|The Santa Anas]]", makes reference to the riots as resulting from the [[Santa Ana winds|Santa Ana Foehn winds]].

Line 113 ⟶ 115:

* The 1994 film ''[[There Goes My Baby (film)|There Goes My Baby]]'' tells the story of a group of high school seniors <!-- where? -->during the riots.

* The producers of the ''[[Planet of the Apes]]'' franchise stated that the riots inspired the ape uprising featured in the film ''[[Conquest of the Planet of the Apes]]''.<ref>{{cite web|last=Abramovich|first=Alex|url=http://www.slate.com/id/112241/|title=The Apes of Wrath |work= Slate Magazine |publisher=Slate.com|date=July 20, 2001|access-date=2011-08-30}}</ref>

* In [[Quantum Leap (season 3)#Episodes|"Black on White on Fire"]], an episode of the television series ''[[Quantum Leap (1989 TV series)|Quantum Leap]]'' which aired November 9, 1990, [[Sam Beckett]] shifts into the body of a black medical student who is engaged to a white woman while living in Watts during the riots.

* Scenes in "Burn, Baby, Burn, Baby, burn, burn, bird", an episode of the TV series ''[[Dark Skies]],'' are set in Los Angeles during the riots.

* The movie ''[[C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America]]'' mentions the Watts riots as a [[slave rebellion]] rather than a riot.