The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003 film)

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a 2003 American slasher film directed by Marcus Nispel in his feature directorial debut, with a screenplay by Scott Kosar. The film stars Jessica Biel, Jonathan Tucker and Erica Leerhsen in lead roles, with Mike Vogel, Eric Balfour, and R. Lee Ermey in supporting roles.

| The Texas Chainsaw Massacre | |

|---|---|

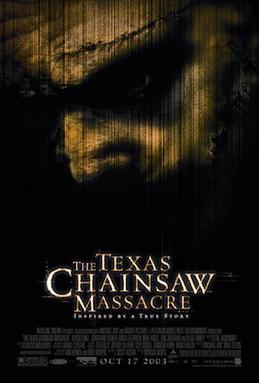

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Marcus Nispel |

| Screenplay by | Scott Kosar |

| Based on | The Texas Chain Saw Massacre by Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Daniel Pearl |

| Edited by | Glen Scantlebury |

| Music by | Steve Jablonsky |

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes[4] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9.5 million[5][6] |

| Box office | $107.4 million[5] |

The plot follows a group of young adults traveling through rural Texas who encounter the sadistic Leatherface and his murderous family. This film is a remake of the 1974 horror classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, directed by Tobe Hooper, and it serves as the fifth installment in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchise. Several original crew members, including Hooper and Kim Henkel, returned as co-producers, with Daniel Pearl reprising his role as cinematographer, and John Larroquette providing the voice narration for the opening intertitles.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre premiered on October 17, 2003 and received negative reviews from critics, who criticized its pacing, writing, and lack of character development. The film emerged as a commercial success at the box-office, grossing over $107 million worldwide on a budget of $9.5 million. The film's success marked the first production by Platinum Dunes, a company that went on to produce remakes of several other notable horror films.

A prequel, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, was released on October 6, 2006, though it received mixed reviews and was less successful at the box-office.

On August 18, 1973, five young adults—Erin, her boyfriend Kemper, Erin’s brother Morgan, and hitchhikers Andy and Pepper—are traveling to a concert after purchasing marijuana in Mexico. While driving through rural Texas, they encounter a traumatized hitchhiker walking aimlessly on the road. She speaks incoherently about "a bad man" before pulling out a revolver and fatally shooting herself.

Seeking help, the group stops at a nearby gas station where a woman named Luda Mae directs them to meet Sheriff Hoyt at a local mill. Upon arriving, they find a boy named Jedidiah, who claims Hoyt is at home drinking. Erin and Kemper leave to search for Hoyt, while the others remain at the mill. The two eventually reach a rundown plantation house, and Erin is let inside by Monty, an amputee, to use the phone. While Erin is inside, Kemper is attacked and killed by Thomas "Leatherface" Hewitt, who drags his body into the basement and mutilates him, finding an engagement ring Kemper had planned to give to Erin.

Back at the mill, Sheriff Hoyt arrives, disposes of the hitchhiker's body, and grows suspicious of the group. When Erin returns to the plantation house with Andy, Leatherface attacks them with a chainsaw. Andy sacrifices himself to allow Erin to escape, but Leatherface captures him, cuts off his leg, and hangs him on a meat hook in the basement. Erin returns to the mill, but Hoyt soon arrives and forces Morgan to reenact the hitchhiker's suicide with an unloaded gun. Hoyt then takes Morgan to the Hewitt house, beating him en route.

Inside the house, Andy tries in vain to escape from the meat hook, while Leatherface terrorizes Erin and the others. As Erin and Pepper attempt to flee, Pepper is killed, and Erin finds herself trapped in a trailer with two women who drug her. She awakens at the Hewitt house, surrounded by the family: Leatherface, Luda Mae, Hoyt, Monty, and Jedidiah. The family reveals Leatherface's disfigurement was caused by a skin disease, and they have taken it upon themselves to care for him.

In the basement, Erin discovers the bodies of Leatherface's previous victims, including Andy, who begs for death. Erin mercifully kills him and rescues Morgan. With Jedidiah's help, they escape the house, but Leatherface catches up and kills Morgan. Erin flees to a slaughterhouse where she severs Leatherface's arm with a meat cleaver, managing to escape.

Erin is eventually picked up by a trucker who stops at the gas station for help. Realizing the danger, she sneaks the kidnapped baby from the family’s care and escapes in the sheriff's car. Hoyt attempts to stop her, but Erin runs him over multiple times, killing him. Leatherface tries to attack her as she drives away, but she escapes with the baby. Two days later, the investigation of the Hewitt house leads to the deaths of two officers at the hands of Leatherface, leaving the case unresolved.

- Jessica Biel as Erin Hardesty

- Jonathan Tucker as Morgan

- Erica Leerhsen as Pepper

- Mike Vogel as Andy

- Eric Balfour as Kemper

- David Dorfman as Jedidiah

- R. Lee Ermey as Sheriff Hoyt

- Andrew Bryniarski as Thomas Hewitt

- Lauren German as Teenage Girl

- Terrence Evans as Old Monty

- Marietta Marich as Luda Mae

- Heather Kafka as Henrietta

- Kathy Lamkin as Tea Lady in Trailer

- Brad Leland as Big Rig Bob

- Mamie Meek as Clerk

- John Larroquette as Narrator

On December 5, 2001, CreatureCorner.com reported that Michael Bay's newly created company, Platinum Dunes, which was established to produce low-budget films, had set its sights on remaking The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Early reports indicated that the remake would be presented in a flashback format, with actress Marilyn Burns—who starred in the original film—reprising her role as an aged Sally Hardesty and recounting the traumatic events of the original story. It was also confirmed that the filmmakers had already secured the rights to the 1974 film.

Initially, it was announced that the original creators, Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel, were involved in writing a script for the remake, though it was unclear if their script would ultimately be used. In June 2002, Marcus Nispel was confirmed to direct the film, marking his feature directorial debut.[7] Nispel admitted that he was initially opposed to the idea of remaking such an iconic film, calling it "blasphemy." However, he was convinced to join the project by his longtime director of photography, Daniel Pearl, who had also shot the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre and wanted to bookend his career by working on both films.[8]

Screenwriter Scott Kosar later signed on to write the screenplay for the remake.[9] Like the original 1974 film, this version was loosely inspired by the real-life crimes of Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, whose gruesome acts also inspired the novels Psycho and The Silence of the Lambs, both of which were later adapted into films.[10]

The screenplay of the film was written by Scott Kosar, who would later write the screenplays for The Machinist and Platinum Dunes' remake of The Amityville Horror.[11][12] This project marked Kosar's first professional job as a screenwriter, and he later recalled feeling both thrilled and honored to have the opportunity to write the script for the remake. Recognizing early on that he was working with "one of the seminal works of the genre," Kosar understood that it would be impossible to surpass the original film. In discussions with the film's producers, Kosar expressed the view that the new version shouldn't attempt to compete with the original, as it had been made under entirely different circumstances.

In earlier drafts of the script, the main character, Erin, was revealed to be nine months pregnant throughout the events of the film. However, this plot point was ultimately removed from later drafts at the insistence of producer Michael Bay.[13]

Jessica Biel, known for her role in the television series 7th Heaven, was cast as the lead character, Erin.[7]

For the role of Leatherface, Andrew Bryniarski, who had previously worked with producer Michael Bay on Pearl Harbor (2001) and remained friends with him, personally approached Bay to express his interest in the part. Initially, another actor, Brett Wagner, was cast in the role. However, Wagner was hospitalized on the first day of filming and was subsequently fired for misrepresenting his physical abilities. With the role of Leatherface suddenly vacant, the filmmakers contacted Bryniarski to offer him the part, which he gladly accepted. In preparation for the role, Bryniarski followed a diet of brisket and white bread, bringing his weight to nearly 300 pounds. Bryniarski would later reprise his role as Leatherface in the film's prequel.[14]

Director Marcus Nispel initially preferred shooting The Texas Chainsaw Massacre remake in California, but producer Michael Bay suggested Texas as the filming location, having previously shot there three times.[15] Principal photography commenced in Austin, Texas, in July 2002 and lasted for 40 days.[16] Nispel aimed to differentiate the remake from the original by employing more traditional narrative techniques, as he did not want to create a shot-for-shot replication of the original's documentary-like style.[17] Cinematographer Daniel Pearl, who also worked on the original 1974 film, explained during an on-set interview: "People ask me, 'Is it going to be as gritty and grainy as the last one I did?' No. I did that. There's no point in making the exact same film with the exact same look."[18]

The remake features nods to the original film, including the return of John Larroquette as the narrator.[19]

The weather during filming was notably hot and humid, which posed challenges for the cast and crew. Andrew Bryniarski, who portrayed Leatherface, performed all of his own stunts while wearing a "fat suit" that increased his weight from nearly 300 lbs to 420 lbs. The suit heated up quickly, requiring Bryniarski to stay hydrated throughout filming. The Leatherface mask, made from silicone, also proved difficult to breathe through. Multiple prop chainsaws were used for Bryniarski, including ones that emitted smoke and others that were live chainsaws.[14]

There were two soundtrack albums released by Bulletproof Records/La-La Land Records for the film; the first was meant for regular audiences featuring popular metal music and was released on November 4, 2003.[20]

The second was the film's original score as composed by Steve Jablonsky. This was released on October 21, 2003, and has a run time of 50:25.[21]

Trailers and TV spots used a version of This Mortal Coil's cover of "Song to the Siren", which was just recorded for the trailer and was sung by the singer Renee of the band Moneypenny.[22]

- "Immortally Insane" by Pantera

- "Below the Bottom" by Hatebreed

- "Pride" by SOiL

- "Deliver Me" by Static-X

- "43" by Mushroomhead

- "Pig" by Seether

- "Down In Flames" by Nothingface

- "Self-Medicate" by 40 Below Summer

- "Suffocate" by Motograter

- "Destroyer of Senses" by Shadows Fall

- "Rational Gaze" by Meshuggah

- "Archetype (Remix)" by Fear Factory

- "Enshrined by Grace" by Morbid Angel

- "Listen" by Index Case

- "Stay in Shadow" by Finger Eleven

- "Ruin" by Lamb of God

- "As Real As It Gets" by Sworn Enemy

- "Five Months" by Coretez

Release and reception

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was released in North America on October 17, 2003, across 3,016 theaters.[23] The film grossed $10.6 million on its opening day and went on to conclude its debut weekend with a total of $29.1 million, ranking number one at the U.S. box office.[23] Seventeen days after its release, the film had grossed over $66 million in the United States alone.[24]

Internationally, the film opened in various countries in the subsequent months, including a Halloween release in the United Kingdom, and earned an additional $26.5 million.[25] With a North American gross of $80.6 million, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre achieved a worldwide total of $107 million.[5] Made on a budget of $9.5 million, the film became the highest-grossing entry in the Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchise, even when adjusted for inflation. As of 2018, the film's inflation-adjusted gross would have exceeded $162 million.[5]

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre received negative reviews from critics, who criticized its pacing, writing, and lack of character development.

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a 37% approval rating based on 159 reviews, with an average rating of 4.9/10. The site's consensus reads: "An unnecessary remake that's more gory and less scary than the original."[26] On Metacritic, the film holds a score of 38 out of 100, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews."[27] However, audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a relatively favorable grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[28]

Critics were divided on the film. Manohla Dargis of the Los Angeles Times praised the film's polished cinematography by Daniel Pearl, while noting: "The remake moves faster and sounds louder, but comes off as callous rather than creepy."[29] Robert K. Elder of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 3 out of 4 stars, calling it "an effectively scary slasher film" despite its absurd premise.[30] William Thomas of Empire rated it 3 stars out of 5, writing, "You'll have to overcome resentment towards this unnecessary remake before you can be properly terrorized, but on its own terms, it plays well."[31]

However, others were more critical. Roger Ebert gave the film 0 stars out of 4, calling it "a contemptible film: Vile, ugly and brutal. There is not a shred of reason to see it."[32] Variety described the film as an "initially promising, but quickly disappointing retread of a hugely influential horror classic."[33] Similarly, Peter Travers of Rolling Stone gave the film 2 stars out of 4, criticizing the film for being "soulless" and stating that while the director Marcus Nispel had a "sharp eye," the film lacked the raw intensity of the original.[34] Dave Kehr of The New York Times echoed these sentiments, calling it a "bilious film" offering "only entrapment and despair."[35]

On SBS' The Movie Show, Australian critic Margaret Pomeranz revealed that this was the first film she walked out of, after just half an hour, refusing to rate it.[36] Fellow host David Statton gave it 1 star, with Pomeranz stating, "I choose to embrace movies, but certain genres, like this one, are not to my taste."[37]

In contrast, Jamie Russell of the BBC offered some praise, calling the film "a gory, stylish, and occasionally scary push-button factory of shocks and shrieks" but questioned why the filmmakers didn’t create an original script or sequel rather than a remake.[25] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave the film two stars out of five, describing it as a "bullish revival" and noting its unsubtle nature but acknowledging the grotesque atmosphere.[38]

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was released on VHS and DVD on March 30, 2004, by New Line Home Entertainment.[39] The standard edition included special features such as seven TV spots, a soundtrack promo, trailers, and a music video for "Suffocate" by Motograter. On the same day, a two-disc Platinum Series Edition was released, featuring a collectible metal plaque cover and an array of additional content. This edition included three filmmaker commentaries (with producer Michael Bay, director Marcus Nispel, and others), crime scene photo cards, deleted scenes, an alternate opening and ending, and documentaries such as Chainsaw Redux: In-Depth and Gein: The Ghoul of Plainfield. Other features included cast screen tests, an art gallery, the "Suffocate" music video, a soundtrack promo, and DVD-ROM content, including a script-to-screen feature.

A UMD version of the film was released on October 4, 2005, followed by its Blu-ray release on September 29, 2009.[40][41]

Stephen Hand authored a novelization of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which was published on March 1, 2004, by Black Flame.[42] Hand had previously written the novelization for Freddy vs. Jason, also for New Line and Black Flame.[43]

A prequel to the film, titled The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, was released on October 6, 2006. Set four years prior to the events of the 2003 remake, the film explores the origins of Leatherface and his family's murderous tendencies.

The financial success of the film spurred a wave of horror film remakes throughout the 2000s and 2010s. Influenced by its success, numerous franchises revisited their original films, including House of Wax, The Wicker Man, The Omen, Halloween, My Bloody Valentine 3D, Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Child's Play. These remakes, however, were generally met with mixed to negative reviews and have been heavily criticized by both audiences and critics for being unnecessary additions to their respective franchises.[44]

- ^ International sales were originally going to be handled by Good Machine;[2] however Focus Features took over after Good Machine was merged with it.

- ^ a b c d "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (April 17, 2005). "Platinum rides 'Hitcher' redo". Variety. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Goodridge, Mike (February 27, 2004). "Bay's Platinum Dunes signs international agreement with Focus". Screen International. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

Focus had previously handled Platinum Dunes' debut project The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which grossed more than $100m worldwide.

- ^ "THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE (18)". British Board of Film Classification. September 26, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Financial Information for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (October 8, 2009). "Twisted moves to 'Texas'". Variety. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ a b "Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The - Mania.com". Mania.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- ^ Pollard, Andrew. "Marcus Nispel | THE ASYLUM, TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE, FRIDAY THE 13TH". Starburst. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Harris, Dana (June 18, 2002). "Horror redo 'Chainsaw' catches Biel, Balfour". Variety. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Rachael Bell and Marilyn Bardsley. "Ed Gein: The Inspiration for Buffalo Bill and Psycho". truTV. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 22, 2004). "Insomnia and Then Emaciation; Now Paranoia Takes Its Turn". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ Condit, Jon (April 13, 2005). "Kosar, Scott (The Amityville Horror)". Dread Central. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ Ain't It Cool News Staff. "Mr. Beaks Interviews Marcus Nispel, TEXAS CHAINSAW Remake Director!!". Ain't It Cool NEws. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ a b "Interview with Andrew Bryniarski". texaschainsawmassacre.net. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Harris, Dana (May 7, 2002). "Nispel to direct remake of 'Chainsaw Massacre'". Variety. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Head, Steve (October 14, 2003). "An Interview with Michael Bay". IGN. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Patrizio, Andy (March 25, 2004). "An Interview with Marcus Nispel". IGN. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ O'Connell, Joe (September 6, 2002). "'Chainsaw' production revving up". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. pp. E3, E5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Elliott-Smith 2016, p. 181.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)". The Soundtrack Info Project. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (score) (2003)". The Soundtrack Info Project. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Official Trailer #1 - (2003) HD, October 9, 2011, retrieved June 26, 2022

- ^ a b "'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' gets a $29.1 million slice of box office". The Odessa American. Odessa, Texas: Associated Press. October 20, 2003. p. 4C – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Connell, Joe (November 7, 2003). "A sequel for 'Chainsaw' remake?". Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. p. E7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Russell, Jamie (October 31, 2003). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". BBC Films. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Metacritic.com. Metacritic. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (October 17, 2003). "'Massacre': gory with little story". Los Angeles Times. p. E6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Elder, Robert K. (October 17, 2003). "'Texas Chainsaw Massacre' is one sharp horror remake". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, William (October 28, 2015). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Review". Empire. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 17, 2003). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (October 17, 2003). "Review: 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre'". Variety. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Travers, Peter (October 17, 2003). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (October 17, 2003). "Another Long March to the Slaughterhouse". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Review". SBS Movies. November 30, 2003. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ "Margaret Pomeranz reveals worst movie she's ever seen". NewsComAu. January 22, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (October 31, 2003). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". The Guardian. London. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003)". IGN. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) UMD VIDEO". psp.ign.com. August 8, 2012. Archived from the original on August 7, 2006. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Keefer, Ryan (October 18, 2009). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ Hand, Stephen (2004). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. BL Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84416-060-0.

- ^ Hand, Stephen; Shannon, Damian; Swift, Mark J. (2003). Freddy vs. Jason (New Line Cinema): Stephen Hand: 9781844160594: Amazon.com: Books. Black Flame. ISBN 1844160599.

- ^ Kondrak, Greg (August 4, 2020). "10 Of The Worst Horror Movie Remakes, According To IMDb". ScreenRant. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- Elliott-Smith, Darren (2016). "Queer Erotic Aesthetics in Texas Chainsaw Massacre". In Clayton, Wickham (ed.). Style and Form in the Hollywood Slasher Film. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-49647-8.

- Knöppler, Christian (2017). The Monster Always Returns: American Horror Films and Their Remakes. New York: transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-839-43735-3.

- Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at AllMovie

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at Box Office Mojo

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at IMDb

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at Metacritic

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at the TCM Movie Database