History of Saturday Night Live

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

American sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live (SNL) debuted on October 11, 1975 on NBC, and quickly developed a cult following.

Development: 1974–1975

Beginning in 1965, NBC network affiliates broadcasted reruns of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson on Saturday or Sunday nights. In 1974, Johnny Carson petitioned to NBC executives for the weekend shows to be pulled and saved so they could be aired during weeknights, allowing him to take time off.[1][2] In response, NBC president Herbert Schlosser approached the vice president of late-night programming, Dick Ebersol, and asked him to create a show to fill the Saturday night time slot.[3] The network had a weak Saturday night lineup at the time that garnered poor ratings,[4] and networks had little interest in late-night Saturday shows until the mid-1970s.[2] At the suggestion of Paramount Pictures executive Barry Diller, Schlosser and Ebersol then approached Lorne Michaels. Over the next three weeks, Ebersol and Michaels developed the latter's idea for a variety show featuring high-concept comedy sketches, political satire, and music performances that would attract 18- to 34-year-old viewers.[5][6] NBC decided to base the new show at their studios in 30 Rockefeller Center. Michaels was given Studio 8H, a converted radio studio that was home to NBC's election and Apollo moon landing coverage. It was revamped for the premiere at a cost of $250,000.[7]

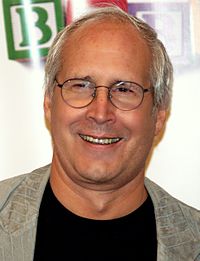

By 1975, Michaels had assembled a talented cast, including Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Jane Curtin, Garrett Morris, Laraine Newman, Gilda Radner, and George Coe.[8] The cast was nicknamed the "Not Ready For Prime-Time Players",[9][10][11] a term coined by show writer Herb Sargent.[12] Much of the talent pool involved in the inaugural season was recruited from The National Lampoon Radio Hour,[13][14] including the original head writer, Michael O'Donoghue.[15]

Radner was the first person hired after Michaels himself.[16] Although Chase became a performer, he was hired on a one-year writer contract and refused to sign the performer contract that was repeatedly given to him, allowing him to leave the show after the first season.[17] Newman was brought aboard after having a prior working relationship with Michaels.[18] Morris was initially brought in as a writer, but attempts to have him fired by another writer led Michaels to have Morris audition for the cast, where he turned in a successful performance.[19] Curtin and Belushi were the last two cast members hired.[20] Belushi had a disdain for television and had repeatedly turned down offers to appear on other shows, but decided to work with the show because of the involvement of Radner and writers Anne Beatts and O'Donoghue.[21] Michaels was still reluctant to hire Belushi, believing he would be a source of trouble for the show, but Beatts, O'Donoghue, and Ebersol successfully argued for his inclusion.[21] NBC executives insisted that Coe join the cast to balance out Michaels's younger selections.[22]

The original theme music was written by Howard Shore, who was the original bandleader.[23] The show was originally conceived with three rotating permanent hosts: Lily Tomlin, Richard Pryor, and George Carlin. According to Ebersol, consideration was given to Steve Martin and singer Linda Ronstadt also being included as a duo.[24] When Pryor dropped out because his brand of comedy was not censor-friendly, the concept was dropped.[25]

Debut and early years: 1975–1979

First weeks

Debuting on October 11, 1975,[6] with an episode featuring Carlin as host,[26] the show quickly gained a cult following.[27] The show was originally called NBC's Saturday Night, because the Saturday Night Live title was in use by Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell on the rival network ABC. After the cancellation of Cosell's show in 1976, NBC purchased the rights to the name and officially changed the show's name to Saturday Night Live at the start of the 1977–1978 season.[2][28][29]

The cast was initially paid $750 per episode, and essentially lived at the offices, according to Michaels.[30][28] Early episodes were more experimental with the show's format; segments from The Muppets were frequently featured in the first season, and the second episode featured eleven musical performances from host Paul Simon, with minimal appearances by the cast. The show was also initially billed as a variety show and did not emphasise the cast. The cast's improvisational backgrounds allowed them to experiment with different forms of comedy.[11]

During the first season, some NBC executives were not satisfied with the show's Nielsen ratings and shares.[31] Michaels pointed out that Nielsen's measurement of demographics indicated that baby boomers constituted a large majority of the viewers who did commit to watching the show, and many of them watched little else on television.[32] In 1975 and 1976, they were the most desirable demographic for television advertisers, even though Generation X was the right age for commercials for toys and other children's products. Baby boomers far outnumbered Generation X in reality, but not in television viewership, with the exception of Michaels's new show and major league sports, and advertisers had long been concerned about baby boomers' distaste for the powerful medium. Executives eventually understood Michaels's explanation of the desirable demographics, and decided to keep the show on the air, despite angry letters and phone calls the network received from some offended viewers over certain sketches.[33]

Pryor episode

The seventh episode hosted by Richard Pryor was an important one for Michaels, who had insisted on booking Pryor as host, feeling that he could aid in making the show more modern.[34] However, he was ordered by NBC network officials to run the episode on a five-second tape delay.[35] The show's previous six episodes had all aired live on the East Coast.[36] NBC officials had expressed concerns about Pryor's content and the possibility of profanity prior to the broadcast.[37] He was initially disallowed as host entirely, until Michaels threatened to walk off the show in protest.[36] Officials then pushed for a ten-second delay, which Michaels negotiated down to five seconds.[38] Pryor, as the first person of color to host the show, found the delay to be an insult, having only found out after the broadcast, and objected to being treated differently to other comedians.[36]

Dave Wilson, SNL's long-time director, later said that the show was in fact broadcast live, as his crew did not know how to work the delay.[39] However, the first edition of The Book of Lists, describing the broadcast, indicated that two words were deleted from the broadcast during Pryor's opening monologue, although what was censored is not specified.[37] NBC reportedly re-engineered their taping machines of the time to create the delay, so that the show would be taped on one machine, and then entirely transferred to another machine for the broadcast.[36] A sketch from this episode featuring Pryor and cast member Chevy Chase, "Word Association", is considered one of the most famous SNL sketches of all time.[40][41]

Rising success

SNL's humor soon began to be seen as refreshing and daring, in comparison to previous sketch and variety shows that would rarely deal with controversial topics and issues.[42] Iconic characters during this period of the show included Belushi's samurai, the Coneheads (Aykroyd, Curtin, Newman), and Radner's Roseanne Roseannadanna.[43]

Chase was the first performer to say the show's introduction line in the first episode,[28] and would say it in every episode for the rest of the season.[44] He was the first anchor of the show's recurring "Weekend Update" segment, and therefore received more screen time than the rest of the cast. Physical comedy and exaggerated pratfalls became his trademark, and he became the show's first breakout star. His impression of Gerald Ford during the 1976 presidential election was later cited as a factor in Ford's subsequent failure to win re-election.[44][45] Chase's success led to tensions with the rest of the cast, particularly Belushi. The network also wanted him for a prime-time show, and he soon left the show during the 1976–77 season.[46] He was replaced by Bill Murray, whom Michaels had intended to hire for the initial cast but was unable to because of budget restrictions.[47] Murray had a shaky start, but by the end of the second season, had begun to develop a following, with a sleazy know-it-all persona and characters such as Nick the Lounge Singer that became popular with audiences.[48]

Tensions

Morris felt underutilised by the writers, and was often assigned sketches that involved racial stereotypes. One of these was a planned "Tarbrush" sketch that would dull African-Americans' supposedly shiny teeth, which was pulled at the last minute by Michaels.[49] Radner, meanwhile, was resented by many because she and Michaels had spent much of the year working on a Broadway play and album, Gilda Live.[50] She had recently broken off a relationship with Murray, and the two could barely speak to one another.[51] Murray resented that the other male cast members had left him stranded and essentially forced him to play every male lead on the show.[52]

Chase returned to host in 1978; during the live telecast, Murray, goaded by Belushi, got into a physical altercation with Chase while musical guest Billy Joel was performing, according to Newman and Michaels in 2002.[53] Chase later said the incident was actually right before the show's monologue.[54] Chase's departure for film had made Michaels possessive of his talent; he threatened to fire Aykroyd if he accepted the role of D-Day in the 1978 comedy Animal House, and later refused to allow SNL musician Paul Shaffer to participate in The Blues Brothers.[55][56]

Drugs were a major problem during the show's first five years. Cocaine had become an "integral part of the working progress" on SNL by the 1978–1979 season, according to Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad.[57] Newman had developed serious eating disorders as well as a heroin addiction, and spent so much time in her dressing room playing solitaire that for Christmas 1979, castmate Radner gave her a deck of playing cards with a picture of Laraine on the face of each card. Radner was also suffering from bulimia.[58][59] Morris began freebasing cocaine, and during rehearsals for an episode hosted by Kirk Douglas, ran screaming onto the set, saying that someone had put an "invisible robot" on his shoulder who watched him everywhere he went. He pleaded with crew to get the robot off of him.[60] During the 1979–1980 season, Michaels had a guard posted outside the elevators on the seventeenth floor. Officially, he was there to keep away fans, but most on the show believed it was to protect against law enforcement.[57]

Aykroyd and Belushi left the show after the 1978–1979 season to make The Blues Brothers.[61] Featured players/writers Al Franken and Tom Davis contributed more heavily in the following season, giving themselves more prominent roles.[62] Another surprise contributor was writer Don Novello, whose "Father Guido Sarducci" character was especially popular and appeared repeatedly during the season.[63] This season would see the hiring of many writers as featured players, usually temporarily. Harry Shearer was the only one promoted to repertory status.[64]

Michaels's departure, Jean Doumanian and Dick Ebersol years: 1980–1984

Michaels and cast departures, Jean Doumanian years

As the fifth season ended in 1980, Michaels, emotionally and physically exhausted, asked executives to place the show on hiatus for a year in order to allow him time to pursue other projects.[65] Concerned that the show would be cancelled without him, Michaels suggested writers Al Franken, Tom Davis, and Jim Downey as his replacements. NBC president Fred Silverman disliked Franken and was infuriated by his Update routine on May 10, 1980, called "A Limo for a Lame-O", a critique of Silverman's job performance and his insistence on traveling by limousine at the network's expense. Silverman blamed Michaels for approving this Weekend Update segment.[66] Unable to secure the deal that he wanted, Michaels chose to leave NBC for Paramount Pictures, intending to bring associate producer Jean Doumanian along with him. Michaels later learned that Doumanian had been given his position at SNL after being recommended by her friend, NBC Vice President Barbara Gallagher.[67]

The remaining cast appeared together for the last time on May 24, 1980, the final episode of the season, hosted by long-time host Buck Henry, who never again returned to host. Almost every writer and cast member, including Michaels, left the show after this episode.[68] Brian Doyle-Murray was the only writer to stay on for the following season.[69]

The reputation of the show as a springboard to fame meant that many aspiring stars were eager to join the new series. Doumanian was tasked with hiring a full cast and writing staff in less than three months, and NBC immediately cut the show's budget from the previous $1 million per episode down to just $350,000. Doumanian also faced resentment and sabotage from the remaining Michaels staff.[70] Cast member Harry Shearer, who disliked Michaels, informed Doumanian that he would stay as long as she let him completely overhaul the program. Doumanian refused, so Shearer also left.[71]

The Doumanian-era cast faced immediate comparisons to the beloved former cast and was not received favorably by critics. Ratings were significantly down for the new season, and audiences failed to connect to the original cast's replacements, such as Charles Rocket and Ann Risley.[72] The New York Times wrote that "only the shell remained" of the previous show, and that the new season lacked innovation.[73] Tom Shales wrote that the show was a "snide and sordid embarrassment".[74]

In a February 1981 episode hosted by Charlene Tilton, Rocket used the profanity "fuck" during a sketch.[75] Director Dave Wilson, upon hearing the word, reportedly threw his script down and left the control room, and the incident was cut from the subsequent West Coast broadcast. Rocket later said he was trying to kill time before the show's close and had not meant to utter the word.[76][77] Following this episode, Doumanian was dismissed after only ten months on the job.[78][79]

Dick Ebersol years

Although executives suggested SNL be left to die, Brandon Tartikoff, who succeeded Silverman as network chief in mid-1981, wanted to keep the show on the air, believing the concept was more important to the network than money. Tartikoff turned to Ebersol as his choice for the new producer. Ebersol previously had been fired by Silverman. Ebersol gained Michaels's approval in an attempt to avoid the same staff sabotage that had blighted Doumanian's tenure.[80]

Ebersol fired the majority of Doumanian's hires, except for two comedians, Eddie Murphy and Joe Piscopo.[81] Ebersol originally wanted to bring in John Candy and Catherine O'Hara from SCTV; Candy turned down the offer.[82] O'Hara initially accepted the job, but changed her mind after a production meeting where head writer Michael O'Donoghue screamed at the cast and writers for the show's poor performances and sketches.[83] O'Donoghue himself was fired after a chaotic period where he tried to radically change the show, including trying to fire director Wilson, and asking Ebersol if he could fire announcer Don Pardo live on SNL's air.[84]

Ebersol's first show aired April 11, with appearances by Chevy Chase on Weekend Update, and Al Franken asking viewers to "put SNL to sleep". Ebersol, wanting to establish a connection to the original cast, allowed Franken's mock-serious routine on the air.[85]

Ebersol ran a very different show from Michaels had in the 1970s. Many of the sketches were built less on innovative premises and followed a more "lowest common denominator" approach under Ebersol, according to cast member/writer Tim Kazurinsky.[86] This shift alienated some fans and even some writers and cast members.[87] Ebersol was eager to attract the younger viewers that advertisers craved, and would usually reject any sketches that ran longer than five minutes, so as not to lose the attention of teenagers.[87] Ebersol was not fond of political humor, and he and NBC mostly eschewed jokes about President Ronald Reagan during his time as showrunner.[88] Murphy was credited with much of that era's success,[89] having introduced popular sketches and characters such as Mister Robinson's Neighborhood and Gumby.[90]

Having come from the ranks of management, Ebersol was adept at dealing with the network.[91] Later in his tenure, he was handling much of the business aspects and day-to-day production affairs, leaving producer Bob Tischler in charge of most of the creative facets of the show.[92]

With the departure of Murphy and much of the cast after the 1983–1984 season, the show appeared talent-deprived. Producers broke with history for the 1984–1985 season by hiring established comedians such as Billy Crystal and Martin Short who could bring their already successful material to the show.[93] Crystal had been scheduled to appear in the first episode in 1975, but walked away after a timing argument during rehearsals.[94] He created characters during this season, such as Fernando, that were popular with audiences.[95] The hirings had come at an inflated cost, however; Crystal and Short were paid $25,000 and $20,000 per episode respectively, far more than earlier salaries.[93] This season was considered one of the series' funniest, but had strayed far from Michaels' innovative approach in the eyes of audiences.[96][97]

After this season, several cast members had grown tired of the show's demanding production schedule and showed little interest in returning for another season, leaving Crystal the only established member available for the following season. Like Michaels five years earlier, Ebersol made it known to NBC that he would only return to SNL if the network would take the show off the air for several months to recast and rebuild.[98] He wanted to attempt a more significant revamp of the show, including largely departing from the show's established live format.[99] NBC turned down Ebersol's requests and decided to continue production only if they could get Michaels to produce again.[98]

Michaels returns: 1985–present

1985–1986 season

Following unsuccessful forays into film and television, in need of money, and eager not to see Tartikoff cancel the show, Michaels decided to return for the 1985–1986 season. The show was again recast, with Michaels borrowing Ebersol's idea to seek out established actors such as Randy Quaid and Anthony Michael Hall, as well as younger stars like Robert Downey Jr. and Joan Cusack.[65] Michaels also expressed a desire to let a new generation "create it in its own image", seeking to appeal to a younger target audience.[100]

Writers found it difficult to write sketches for the eclectic new cast, which was reportedly put together in just six weeks.[101] The season premiere, hosted by Madonna, received "scathing" reviews according to The New York Times;[100] writer Downey later said the episode was one of the worst in the show's history.[102] Head writer Franken was later critical of Michaels' decision to seek a younger cast, observing that it was "impossible to write a Senate hearing", and Ebersol later called the year "very dark".[101] The season overall is considered one of the show's worst.[103] In April 1986, Tartikoff again made the decision to cancel the show, until he was convinced by producer Bernie Brillstein to give it one more year.[104]

Insert title here

The show was renewed for the 1986–1987 season, but, for the first time in its history, for only thirteen episodes instead of the usual twenty-two.[105] Michaels again fired most of the cast, and unlike the previous seasons, sought out unknown talent such as Dana Carvey and Phil Hartman instead of known names.[106] Only a few cast members from the previous season were retained, such as Jon Lovitz, Nora Dunn, and Dennis Miller, whose hosting of Weekend Update had been a source of praise.[107] The October 11 premiere hosted by Sigourney Weaver opened with Madonna reading a mock NBC statement that the previous season had been "a dream... a horrible, horrible dream".[108]

This new cast was successful at reviving the show's popularity in the eyes of critics and audiences.[109] The Washington Post observed that the show had "new life", crediting Carvey in particular.[110] It was considered a more disciplined, straight cast than previous eras, with less alcohol and drug use.[111] Lovitz was known for playing sleazy, obnoxious characters such as Tommy Flanagan, a pathological liar, and Carvey's impressions of celebrities like John Travolta quickly proved popular. He also created popular new characters such as Church Lady and the Grumpy Old Man.[112] The Church Lady's mannerisms was inspired by NBC's increased censorship of the show compared to the initial years, which Carvey and Dunn criticised.[111] Michaels had also reintroduced political humor to the show, and Carvey's impression of George H.W. Bush is considered one of the best presidential impressions in the show's history.[113]

The new core group of eight would be unchanged for the next four years,[114] excluding the addition of Mike Myers in 1989.[115] A two-and-a-half-hour prime time special aired on September 24, 1989, to celebrate the series' fifteenth year on the air. Original cast members Chase, Aykroyd, Curtin, Morris, Newman all returned along with other cast and crew, with tributes to the late Belushi and Radner. Michaels said he and Tartikoff wanted to bring the "old" and "new" casts together to celebrate.[116]

Controversial comedian Andrew Dice Clay hosted the show on May 12, 1990, which prompted cast member Dunn to boycott the episode that week. Her actions were perceived as a publicity stunt by some involved with the show's production. After the cast took a vote, Dunn was not invited back to the cast for the following season.[117]

"Bad Boys" era

In the early 1990s, much of this core cast began to leave the show (such as Carvey and Dennis Miller), and younger performers such as Chris Farley and Adam Sandler began to be promoted to repertory status. Carvey later remarked that these cast members were "bursting with energy" and that it was a natural time to transition to a newer cast.[118] Of the new cast members, Farley often used his size and physicality in sketches, like in the "Chippendales Audition" sketch alongside Patrick Swayze.[119]

Some of these cast members, like Sandler, Farley, Rob Schneider, David Spade, and Chris Rock, would come to be known as the "Bad Boys of SNL" for their outrageous comedy style.[119] They remained fairly close in the years after they left the show, often appearing in each other's movies.[119] Many of the sketches written by this newer cast mocked authority; some critics described it as "frat boy" humor, filled with profane language and jokes about bodily functions.[118] Afraid of cast members leaving for film careers, Michaels had overcrowded the cast, causing a divide between the veteran members and the new, younger talent. This led to increased competition for the show's limited screen time, and an increasing reliance on "younger", less subtle humor.[121]

An epynomous film based on Carvey and Myer's "Wayne's World" sketch was released on February 14, 1992, and was a critical and commercial success.[122][123] Michaels had over the years approved several films based on SNL characters, attempting to recapture the success of The Blues Brothers, to varying amounts of success. Wayne's World was the only SNL film to gross over $100 million at the box office.[124]

The show ran successfully again until it lost Carvey and Hartman, two of its biggest stars, between 1992 and 1994. Wanting to increase SNL's ratings and profitability, NBC West Coast president Don Ohlmeyer and other executives began to actively interfere in the show, recommending that new stars such as Chris Farley and Adam Sandler be fired and critiquing the costly nature of performing the show live. The show faced increasing criticism from the press and cast, in part encouraged by the NBC executives hoping to weaken Michaels's position.[125] Michaels received a lucrative offer to develop a Saturday night project for CBS during this time, but remained loyal to SNL.[126]

Sinéad O'Connor

On October 3, 1992, Sinéad O'Connor appeared, performing an a cappella performance of Bob Marley's "War".[127] During the dress rehearsal of the episode, O'Connor held up a photo of a Balkan child as a protest of child abuse in war before bowing and leaving the stage, which the episode's director Dave Wilson described as a "very tender moment".[128] However, during the live show, O'Connor changed the "War" lyric "fight racial injustice" to "fight child abuse" as a protest against the then still relatively unknown cases of sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church. She presented a photo of Pope John Paul II while singing the word "evil", before tearing the image into pieces and saying "Fight the real enemy!"[128][129]

NBC had no foreknowledge of O'Connor's plan, and Wilson purposely failed to use the "applause" button, leaving the audience to sit in silence.[128] The network received thousands of irate calls in the aftermath of the incident, and protests against O'Connor occurred outside of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, where a steamroller crushed dozens of her tapes, CDs, and LPs.[128] In the following weeks on SNL, Catholic guests Joe Pesci and Madonna both voiced their opposition to O'Connor,[128][129] and she was banned for life from the network.[130] The show also aired several sketches mocking O'Connor, such as an impression by Jan Hooks that invited the audience to boo.[131] The incident occurred nine years before John Paul II, in a 2001 apology, acknowledged that the sexual abuse within the Church was "a profound contradiction of the teaching and witness of Jesus Christ",[132] followed in 2008 by Pope Benedict XVI apologizing and meeting with victims, speaking of his "shame" at the evil of abuse, calling for perpetrators to be brought to justice, and denouncing mishandling by church authorities.[133][134] O'Connor later said she had "no regrets" about the performance in 2021, saying it was "brilliant [...] but it was very traumatising". She never appeared on Saturday Night Live again prior to her death on July 26, 2023.[130]

1995–96 overhaul

Hartman's loss was noted as a significant loss for the show. Hartman gave an interview to TV Guide in which he said he felt like he had gotten off the Titanic.[135]

Chris Rock left the show in 1993 after three years as a cast member, later criticising the show for limiting him to stereotypically Black roles.[136]

Following what was widely referred to as a subpar year for the show, nine cast members, including Myers, Nealon, Sandler, and Farley, left the show after the 1994–95 season. Only five members of the cast returned for the following season, which added a number of performers that would become important to the show, including Will Ferrell, Cheri Oteri, and Darrell Hammond.[137] Ferrell and Oteri introduced the Spartan cheerleaders, while Molly Shannon introduced her character, Mary Katherine Gallagher, who would later get a spin-off film in 1999.[138] Tina Fey would become the show's first female head writer in 1999.[28]

In the mid-90s, the show focused on performers, and writers were forced to supply material for the cast's existing characters before they could write original sketches.[139]

Norm Macdonald on Weekend Update

Norm Macdonald was made the host of Weekend Update beginning with the 1994–1995 season, taking over from Kevin Nealon; Bill Maher and Franken were other contenders for the role.[140] He was notable for making frequent jokes about the criminal trial of O.J. Simpson, who was accused of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown. After Simpson's controversial acquittal in October 1995, Macdonald opened the segment with the joke, "Well, it is finally official. Murder is legal in the state of California."[140]

Don Ohlmeyer, a network executive that oversaw Michaels and SNL, was a longtime friend of Simpson's, and at one point even left a meeting early at SNL in order to visit Simpson in jail. He was unhappy with the continuing Simpson jokes; though he did not communicate with Macdonald directly, he made his displeasure regarding Macdonald and Update writer Jim Downey known to Michaels regularly. During the 1997–1998 season, Ohlmeyer had Downey removed from the segment, and told Macdonald he could stay, but only under a new writing staff. Macdonald refused to perform the segment without Downey, and was then removed from Update.[140] Colin Quinn was made the new Update anchor.[141] Ohlmeyer later argued that ratings had been declining for the segment under Macdonald, which had not occurred previously during the segment.[142] Macdonald returned to host two years later in 1999, making fun of the firing in his monologue.[143]

2000s

Fallon and Fey began hosting Weekend Update as a team in 2000.[144]

September 11 attacks and anthrax scare

The show's New York City cast and crew were highly impacted by the September 11 attacks in 2001. Many entertainment programs were halted or postponed following the attacks, but late-night programs such as SNL began planning to return to the airwaves.[145] SNL's scheduled Reese Witherspoon episode, the September 29 season premiere for the 2001–2002 season, aired as planned. Producer Steve Higgins later said that he wanted to do something to "bring normalcy back" following the show's return, which occurred twelve days after talk show host David Letterman had returned to the air.[146]

New York mayor Rudy Giuliani spoke at the top of the show standing with NYC firefighters and police officers, including Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik and Fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen, followed by a performance of "The Boxer" from Paul Simon. Giuliani called the emergency workers heroes, which was applauded by the studio audience.[147] He also made mention of the victims of the attacks, hailing them as heroes also.[148] After Michaels asked, "Can we be funny?" Giuliani replied, "Why start now?" to laughter from the audience.[147] The joke was Michaels's idea. Michaels and Giuliani wanted to convey that the city was "open for business" with the episode.[149][146] Giuliani also delivered the show's signature opening line.[150] The episode is considered one of the most memorable in the show's history.[151]

The show took on a more serious tone for the rest of the season, with less political humor.[152] Planned second episode host Ben Stiller dropped out due to the attacks, forcing producers to find a replacement.[146] SNL's 30 Rockefeller Plaza production location was also the subject of an anthrax scare, during the production of Drew Barrymore's episode in October 2001, when an NBC News employee on a lower floor was diagnosed with anthrax after opening a letter in the NBC newsroom. Barrymore considered dropping out of the episode, but decided to continue hosting, citing Giuliani as an inspiration to continue.[152] Head writer Tina Fey later said she had a "panic attack, basically" and left the building, only returning later that night at the urging of Michaels.[146]

SNL Digital Shorts

The Lonely Island, a comedy trio composed of Andy Samberg, Akiva Schaffer, and Jorma Taccone, were hired by SNL for the 2005–2006 season, following a writing gig for the 2005 MTV Movie Awards that was hosted by Jimmy Fallon.[153] Fallon's praise, and positive word of mouth to others like Fey and Michaels, had led the trio to audition in mid-2005. Samberg was hired as a cast member, while Schaffer and Taccone joined the writing staff.[154]

Schaffer and Taccone struggled initially, with only two of their sketches making it to air in the first three months.[155] They soon saw success incorporating more video work, deciding to bypass the pitching process, as they were so new to the show that it would have been dismissed as too expensive.[156][157] Their breakthrough was the short "Lazy Sunday" in December 2005, which had spread nationwide[155] and became one of the first viral YouTube videos.[156] It increased the trio's recognisability, particularly Samberg's, nearly overnight.[155] Their success, according to New York, "forced NBC into the iPod age".[158]

This newfound popularity led to a record deal for the trio and the creation of the SNL Digital Shorts division, which allowed the group creative freedom to continue producing videos.[157] Michaels was often confused by the trio's pitches, and decided to stop taking their pitches and allow them to self-produce their efforts.[153][159] The group's rise to fame was highlighted by a combination of "new" and "old" media, as described by Schaffer.[156]

Many songs recorded for their 2009 album, Incredibad, and following albums Turtleneck & Chain and The Wack Album, would premiere as Digital Shorts on SNL.[160][161] Schaffer and Taccone left SNL in 2010, but stayed on for following seasons to produce Digital Shorts related to their musical work.[159] Samberg left the show in 2012, later calling the decision difficult, but saying he was stressed and "falling apart" due to the workload.[162]

2008 presidential election

Fey later returned to the show during the 2008 presidential election for several critically acclaimed guest appearances as vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin.[163] Michaels called Fey in August 2008 about reprising the role, and the first sketch in which she performed alongside Amy Poehler as Hillary Clinton aired on September 13. During this sketch, writer Mike Shoemaker coined the phrase, "I can see Russia from my house", a line frequently misattributed to Palin herself.[164][165]

Fey won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series in 2009 for her impersonation of Palin.[166] Writer Robert Smigel later said it was the show's "biggest moment since the 70s", and Michaels observed that it made Fey a "huge star" and that "you could see perception changing completely".[167] The show's ratings saw a significant increase during this period.[168]

Palin herself appeared on the show on October 18, 2008, watching and critiquing a sketch from a previous episode in which Fey had played her.[169] She did not appear directly alongside Fey, as Fey was "terrified" of anything resembling a political endorsement, according to Michaels.[170]

Betty White hosting

Obama presidency

Fred Armisen played the role of Barack Obama during the primary season leading up to the 2008 United States presidential election using darkening makeup, which was controversial. Michaels defended the decision to cast Armisen, saying that he hired the performer with the "cleanest" take on Obama.[171] He played Obama from 2008 to 2012, following which cast member Jay Pharoah assumed the impression. Pharoah and Killam were let go in 2016.[172]

Darrell Hammond left the show in 2009 after fourteen years, then holding the record for longest-running cast member (later beaten by Kenan Thompson). He holds a record for the most times saying the show's opening line, saying it over seventy times during his tenure.[28][173]

From 2008, Seth Meyers was the solo host of Weekend Update,[174] before being partnered with Cecily Strong in 2013. After Meyers left for Late Night with Seth Meyers in February 2014, Strong was paired with head writer Colin Jost. However, later that year, she was replaced by writer Michael Che.[175][176]

Long-time performers Bill Hader, Jason Sudeikis and Fred Armisen all left the show after the 2012–2013 season, which prompted the show to add eight performers over the course of the following season, including Beck Bennett and Kyle Mooney.[137][177] In 2014, Sasheer Zamata was added as a cast member mid-season, after criticism of the show's lack of an African-American woman.[178][179][180]

Head writer Colin Jost became a Weekend Update anchor in 2014 alongside Cecily Strong, after Meyers left for Late Night with Seth Meyers. Jost was criticised initially for what some critics saw as a wooden performance,[181] but later received more praise after being paired with Michael Che later in 2014.[182]

The show began to rely more on pre-recorded material and videos more than it ever had before,[183] to the extent that some commentators said it has outshined live material on the show in recent years.[184][185][186]

2016 presidential election

Trump hosted the show on November 7, 2015, while he was a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination. His appearance invited protests outside the building. Cast member Taran Killam later called the appearance "embarrassing and shameful". He had previously hosted in 2004.[187][188]

Trump won the election over Clinton in a surprise victory on November 8, 2016.[189] Dave Chappelle hosted the show's highly-anticipated first post-election episode on November 12 with musical guest A Tribe Called Quest.[190] The show's writing staff, initially expecting Clinton to win the election, were taken by surprise and forced to change course on their planned sketches.[191] During the cold open, a somber Kate McKinnon, as Clinton, covered Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" at a grand piano, closing by saying, "I'm not giving up and neither should you."[190] The cold open was intended both as a tribute to Cohen and as an acknowledgement of the country's divided state following the election.[191] The performance received divided responses; former cast member Rob Schneider said the show was "over" for good after the performance, accusing the show of "comedic indoctrination".[192]

Trump years

The show received positive attention for a recurring impression of Trump by actor Alec Baldwin, which debuted in 2016. Baldwin won an Emmy for his performance.[193][194]

2000s

COVID-19 pandemic

The Hollywood Reporter said that the cast overhaul prior to the 2022–2023 season, in which eight cast members left including long-time cast members such as Kate McKinnon and Cecily Strong, had been the "biggest [...] in a generation". Michaels referred to ongoing disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic as the reason for the large exodus, saying cast members had lacked access to work that they would usually be able to find after leaving SNL.[137][195] Due to the 2023 Writers Guild of America strike, the 49th season was delayed until October 14, 2023.[196]

2020 presidential election

Dave Chappelle hosted the first episode following the 2020 presidential election, in which Joe Biden was elected President, on November 7, 2020.[197]

Joe Biden was played by Jim Carrey through the election.[198] Alex Moffat succeeded Carrey as Biden in November, after the election.[199]

Please Don't Destroy

The trio became prominent on social media sketches, before breaking out on SNL.[200] Sketches featured on the show usually include celebrity performers, such as Taylor Swift in a "Three Sad Virgins" sketch in November 2021. Billboard said the group had "capably picked up the digital short mantle" left on the show by The Lonely Island.[201] The trio starred in a movie, Please Don't Destroy: The Treasure of Foggy Mountain, released on the Peacock streaming service on November 17, 2023.[200]

2024 election

On July 31, it was announced that Maya Rudolph would return to portray Presidential nominee Kamala Harris through the 2024 election season.[202]

SNL 25th anniversary

SNL 40th anniversary

Future

A three-hour prime-time live broadcast to celebrate the series' history will air on February 16, 2025.[203]

In January 2024, Variety said that "speculation [had] been rampant for years" that Michaels would retire from the series after its fiftieth season, premiering in 2024.[204] Michaels told Entertainment Tonight that month that former head writer and cast member Tina Fey could "easily" be his successor, were he to step down, but said he had not made a decision yet at that point. Michaels has worked with Fey several times since her SNL tenure ended, including on 30 Rock.[205]

Michaels earlier said in 2021 that the show's fiftieth anniversary would be "a really good time to leave".[206] Kenan Thompson, the show's longest-serving cast member, speculated in 2022 that SNL may come to an end altogether after its fiftieth season, saying that it could make financial sense for NBC.[207]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Henry & Henry 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Wilson Hunt, Stacy (April 22, 2011). "A Rare Glimpse Inside the Empire of 'SNL's' Lorne Michaels". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Hammill 2004, p. 2008.

- ^ Greenfield, Jeff (February 11, 2015). "New York Magazine's Original 1975 Review of Saturday Night Live". Vulture. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shaw, Gabbi; Olito, Frank (December 20, 2022). "WHERE ARE THEY NOW: All 162 cast members in 'Saturday Night Live' history". Business Insider. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Marx, Sienkiewicz & Becker 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. (April 4, 2011). "'Saturday Night Live' mocks politics with bipartisan gusto". Politico. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Atwater, Carleton (December 7, 2010). "Looking Back at the First Five Years of SNL". Vulture. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Wayne, Teddy (October 29, 2013). "The Lowest Form of Humor: How the National Lampoon Shaped the Way We Laugh Now". The Millions. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (July 3, 2005). "National Lampoon Grows Up By Dumbing Down". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Wright, Megh (November 4, 2014). "Saturday Night's Children: Michael O'Donoghue (1975)". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 19, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 38.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Wright, Megh (July 23, 2013). "Saturday Night's Children: George Coe (1975-1976)". Vulture. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Jeremy (March 11, 2023). "How Lord Of The Rings Composer Howard Shore Built The Original Saturday Night Live Band". /Film. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Tropiano 2013, p. 2.

- ^ "Remembering Carlin on the "SNL" Premiere". Variety. June 23, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e Jones, Abby; Clair, Fiona (October 2, 2021). "22 things you probably never knew about 'Saturday Night Live'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (September 26, 2014). "The Surprising Story Behind Saturday Night Live's Most Famous Line". TIME. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ Sheff-Cahan, Vicki; Schindehette, Susan; Park, Jeannie (September 25, 1989). "'Saturday Night Live' !". People. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 179.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 180.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 187.

- ^ Henry & Henry 2013, p. 168.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Walfisz, Jonny (December 13, 2023). "Culture Re-View: Why Richard Pryor caused NBC to add a time delay to Saturday Night Live". Euronews. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Wallechinsky, Wallace & Wallace 1977, p. 217.

- ^ Henry & Henry 2013, p. 169.

- ^ Henry & Henry 2013, pp. 169–170.

- ^ "50 Greatest 'Saturday Night Live' Sketches of All Time". Rolling Stone. February 3, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Ventre, Michael (December 11, 2005). "Like 'Daddy Rich,' Pryor was a true king". TODAY. NBC News. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 10.

- ^ a b "Top 10 Post-SNL Careers". TIME. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Tinnin, Drew (January 10, 2023). "One Of Chevy Chase's Most Famous Saturday Night Live Bits Sent Him Straight To The Hospital". /Film. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (September 19, 2018). "Chevy Chase can't change". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 46, 101.

- ^ Rome, Emily (January 15, 2016). "On this day in pop culture history: Bill Murray replaced Chevy Chase on 'SNL'". Uproxx. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 238.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 341.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 352.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 351.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 125.

- ^ Peters, Fletcher (June 18, 2021). "Bill Murray and Chevy Chase's Infamous Fight Was "Awful," Say 'SNL' Co-stars". Decider. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Keller, Richard (April 17, 2008). "The Not Ready for Prime-Time Players who made it to the big time: 1975–1985". AOL. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 322.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 353.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 153.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 347.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 358.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 344–345.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, p. 288.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 178–182.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Wright, Megh (February 6, 2013). "Saturday Night's Children: Brian Doyle-Murray (1979-1980; 1981-1982)". Vulture. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 191–192, 195.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 387.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Schwartz, Tony (January 11, 1981). "Whatever happened to TV's 'Saturday Night Live'?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 412.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 431–433.

- ^ DeSantis, Rachel (February 6, 2017). "Saturday Night Live: A history of F-bombs". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 202.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (September 5, 2012). "How Bad Can It Be? Case File #23: Saturday Night Live's aborted 1980-81 season". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 209.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 441.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 444.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 449, 457.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, pp. 222–225.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 452.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, p. 270.

- ^ Meaney, Jake (October 14, 2010). "'Saturday Night Live: The Best of Eddie Murphy' Brings on Bursts of Genius". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, p. 219.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 472.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, p. 255.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 54–56.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 263–265.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 286.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 474.

- ^ a b Saturday Night Live in the '80s: Lost and Found (Documentary). November 13, 2005. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Atwater, Carleton (January 6, 2011). "Looking Back at Saturday Night Live, 1980-1985". Vulture. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Bennetts, Leslie (December 12, 1985). "Struggles at the New 'Saturday Night'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (October 3, 2012). "Younger, Sexier, Inherently Doomed Case File #25: Saturday Night Live's 1985-1986 season". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 307.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 308–313.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 288, 294.

- ^ Grein, Paul (October 9, 2023). "Here's the Host & Musical Guest for Every 'Saturday Night Live' Season Premiere". Billboard. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (September 27, 2013). "The 8 Biggest Transitional Seasons in 'SNL' History". Vulture. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Ryan (July 25, 1987). "Well, Isn't He Special?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 3, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, Lynn (April 17, 1987). "On the Cover: "You can't compete with a memory," says Lorne Michaels". The Vindicator. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Adalian, Josef (June 2, 2017). "How Each Era of SNL Has Ridiculed American Presidents". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 319.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 749.

- ^ Hanauer, Joan (September 20, 1989). "'SNL' celebrates 15th anny reunion". United Press International. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 332–337.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2014, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Siegel, Alan (September 11, 2019). "Comedy in the '90s, Part 3: The Bad Boys of 'Saturday Night Live'". The Ringer. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 360.

- ^ "Wayne's World". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Fox, David J. (March 3, 1992). "Weekend Box Office 'Wayne's World' Keeps Partyin' On". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 372.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Vesey 2013, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e Tapper, Jake (October 13, 2002). "Sin". Salon. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Murray, Noel (March 7, 2006). "Inventory: Ten Memorable Saturday Night Live Musical Moments". A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Gajanan, Mahita (July 26, 2023). "The Controversial Saturday Night Live Performance That Made Sinéad O'Connor an Icon". TIME. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (September 27, 2019). "'S.N.L.' Is Sorry: A Brief History of the Show's (Sort Of) Apologies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ "Pope sends first e-mail apology". BBC News. November 23, 2001. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ "Pope 'deeply sorry' for 'evil' of child abuse". ABC News. July 19, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Wynne-Jones, Jonathan; Squires, Nick (March 20, 2010). "Pope's apology: 'You have suffered grievously and I am truly sorry'". The Telegraph. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Curtis, Bryan (August 27, 2014). "The Glue". Grantland. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 395.

- ^ a b c Porter, Rick (September 30, 2022). "Breaking Down 'SNL's' Biggest Cast Overhaul in a Generation". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 427.

- ^ a b c Edgers, Geoff (April 12, 2024). "The unlikely but enduring bond between Norm Macdonald and O.J. Simpson". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 24, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 432.

- ^ Jackson, Dory (September 14, 2021). "Norm Macdonald's Best Moments from His Time on 'Saturday Night Live' — Watch". People. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Gray, Ellen (December 30, 2000). "Head writer: Timing helped her land job". The Vindicator. Knight Ridder Newspapers. p. B13. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Walfisz, Jonny (September 11, 2023). "Culture Re-View: How 9/11 changed films, music and books for two decades". Euronews. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dickson, EJ; Greene, Andy (September 8, 2021). "'In Bad Times, People Turn to the Show': Inside the 9/11 Episode of 'SNL'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "NYC Mayor on SNL: It's OK to Laugh". ABC News. October 3, 2001. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ McGahan, Michelle (September 11, 2015). "A Look Back At SNL's Powerful 9/11 Tribute". Bustle. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (April 14, 2010). "Saturday Night Live in the 2000s: Time and Again". Variety. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 504.

- ^ Rosario, Alexandra Del (September 11, 2021). "Ming-Na Wen & 'SNL's Keith Ian Raywood Reflect On 9/11 At Creative Arts Emmys: "Twenty Years Ago Completely Changed Our Lives"". Deadline. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b "SNL Goes on Despite Anthrax Scare". ABC News. October 16, 2001. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Becker, Marx & Sienkiewicz 2013, pp. 236–245.

- ^ Jardin, Xeni (September 30, 2005). "Open Source Opens Doors to SNL". WIRED. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Itzkoff, Dave (December 27, 2005). "Nerds in the Hood, Stars on the Web". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Echlin, Hobey (April 30, 2013). "The Lonely Island Guys Prove Once Again Why They're the Internet's Biggest Stars". Paper. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b McGurk, Stuart (April 10, 2012). "The Hits Squad". GQ. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Influentials: TV and Radio". New York. May 3, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Heisler, Steve (May 24, 2011). "Interview: The Lonely Island". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (May 18, 2011). "The Lonely Island: Turtleneck & Chain Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Czajkowski, Elise (June 10, 2013). "Talking to The Lonely Island About 'The Wack Album', 'SNL', and Why They Haven't Done a Live Show Yet". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (July 11, 2024). "Andy Samberg Opens Up About 'Difficult' Decision to Leave 'SNL': 'I Was Falling Apart in My Life'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Poniewozik, James (September 14, 2008). "Fey's Palin? Not Failin'". TIME. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Poehler, Amy (October 29, 2014). "Amy Poehler on What It Was Like to Tape Saturday Night Live While Pregnant". Vulture. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 587–588.

- ^ O'Neil, Tom (September 13, 2009). "You betcha - Tina Fey wins Emmy as Sarah Palin on 'SNL'". The Envelope. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 586–589.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (September 14, 2008). "'SNL' Sees Its Ratings Soar". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Hamby, Peter; Hornick, Ed (October 18, 2008). "Sarah Palin appears on 'Saturday Night Live'". CNN. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 590–591.

- ^ Izadi, Elahe (September 3, 2016). "The most memorable comedy moments of the Obama presidency". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Joanna (August 9, 2016). "Eight Years Later, S.N.L. Still Has an Obama Problem". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Gallagher, Danny (October 4, 2023). "A Look at Some of the Longest-Running SNL Cast Members and What Kept Them on Air". Paste. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Gross, Doug (September 15, 2009). "Seth Meyers says he'll man 'SNL' Update desk alone". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Cooper (January 23, 2014). "'SNL' head writer to join Cecily Strong as 'Weekend Update' co-anchor shingbauer". Today. NBC News. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Ge, Linda; Maglio, Tony (September 11, 2014). "Saturday Night Live' Replaces Cecily Strong With Michael Che as 'Weekend Update' Anchor". Yahoo!. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Graham, Mark (September 28, 2013). "Meet The Six New Faces on Saturday Night Live". VH1. Viacom Media Networks. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (January 6, 2014). "Meet the New 'SNL' Cast Member". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (January 6, 2014). "Upright Citizens Brigade alum Sasheer Zamata will join the late-night sketch series Jan. 18". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Carter, Bill (January 6, 2014). "'S.N.L' Hires Black Female Cast Member". The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Greenberg, Rudi (March 5, 2014). "When a 'Weekend Update' anchor is as mediocre as Colin Jost, all you can do is shrug". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Rowles, Dustin (April 17, 2023). "'Update' Anchors Michael Che and Colin Jost Are Good at their Jobs". Pajiba. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 667.

- ^ Parton, Brad (January 23, 2014). "The Evolution of 'SNL's Pretaped Sketches and Digital Shorts". Vulture. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Wicks, Amanda (January 29, 2023). "SNL Is Excelling in One Particular Way". The Atlantic. Retrieved 24 August 2024.

- ^ Boyle, Michael (January 22, 2022). "Why Please Don't Destroy's Warp-Speed Absurdity Is the Future of Saturday Night Live". Slate. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Chris; Robinson, Joanna. "Saturday Night Live's Wildest, Weirdest, and Most Regrettable Hosts". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 27, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Vitali, Ali (November 8, 2015). "Donald Trump Hosts 'Saturday Night Live' Amid Protests". NBC News. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Flegenheimer, Matt; Barbaro, Michael (November 9, 2016). "Donald Trump Is Elected President in Stunning Repudiation of the Establishment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Bowman, Emma (November 13, 2016). "'SNL' Strikes A Somber Tone In Post-Election Episode". NPR. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Light, Alan (May 26, 2022). "'More Than Just a Song': How Kate McKinnon Pulled Off the SNL 'Hallelujah' Cold Open". Esquire. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (August 31, 2022). "Rob Schneider: Kate McKinnon Singing 'Hallelujah' as Hillary Clinton Killed 'SNL' and 'It's Not Going to Come Back'". Variety. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Konerman, Jennifer (October 1, 2016). "Alec Baldwin Debuts as 'SNL's' Trump: "I Have the Best Judgment"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Bradley, Laura. "Alec Baldwin Wonders: Is His S.N.L. Trump Impression "Too Cuddly"?". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ White, Peter (September 15, 2022). "'SNL' Adds Four Featured Players: Marcello Hernandez, Molly Kearney, Michael Longfellow & Devon Walker". Deadline. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ White, Peter; Grobar, Matt (October 4, 2023). "'SNL': Pete Davidson & Bad Bunny Among Hosts As NBC Show Sets Returns With SAG-AFTRA Blessing, Full Cast Comes Back For Season 49 & Chloe Troast Joins". Deadline. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Kelley, Sonaiya (November 8, 2020). "Here's how Dave Chappelle's 'SNL' post-election monologue compares to his 2016 stand-up". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Maglio, Tony (September 16, 2020). "Jim Carrey to Play Joe Biden on Season 46 of 'SNL'; Show Adds 3 to Cast". The Wrap. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Drury, Sharareh; Upadhyaya, Kayla Kumari (20 December 2020). "'SNL': Alex Moffat Replaces Jim Carrey as Joe Biden in Cold Open". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Pandya, Hershal (May 8, 2023). "Please Don't Destroy? More Like Please Do Make a Movie". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (November 7, 2023). "Please Don't Destroy Members Still Can't Believe Taylor Swift Agreed to 'Three Sad Virgins' Bit Either". Billboard. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie; White, Peter (July 31, 2024). "Maya Rudolph To Play Kamala Harris On 'Saturday Night Live' Through 2024 Presidential Election". Deadline. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (May 10, 2024). "'SNL' to Mark 50th Anniversary With a Live Primetime Special (on a Sunday)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (January 17, 2024). "'SNL' Without Lorne Michaels? "It Could Easily be Tina Fey," Creator Says". Variety. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Sloop, Hope (February 27, 2024). "Why Adam Sandler Does Not Think Lorne Michaels Is Retiring From 'Saturday Night Live' Yet (Exclusive)". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Brathwaite, Lester (December 20, 2021). "Lorne Michaels eyeing retirement from SNL at show's 50th anniversary — in 3 years". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Chris (August 1, 2022). "Kenan Thompson Thinks Ending SNL at 50 "Might Not Be a Bad Idea"". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

Works cited

- Becker, Ron; Marx, Nick; Sienkiewicz, Matt (October 2, 2013). Saturday Night Live and American TV (1st ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253010-90-X.

- Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle (2003). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present (8 ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345455420.

- Henry, David; Henry, Joe (November 5, 2013). Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World That Made Him. Algonquin Books. ISBN 9781616200787.

- Hill, Doug; Weingrad, Jeff (1986). Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live. Beech Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-688-05099-3.

- Hammill, Geoffrey (2004). "Saturday Night Live". In Newcomb, Horace (ed.). Encyclopedia of Television. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Fitzroy Dearborn (published 2014). ISBN 978-1-135-19479-6.

- Kaplan, Arie (August 1, 2014). Saturday Night Live: Shaping TV Comedy and American Culture. 21st Century. ISBN 1-467710-86-5.

- Marx, Nick; Sienkiewicz, Matt; Becker, Ron (2013). "Introduction: Situating Saturday Night Live in American Television Culture". Saturday Night Live and American TV. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-253-01090-2. JSTOR j.ctt16gznsz.4.

- Shales, Tom; Miller, James Andrew (October 6, 2015). Live From New York: The Complete, Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live as Told by Its Stars, Writers, and Guests (2nd ed.). Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-29506-2. LCCN 2014943177.

- Tropiano, Stephen (2013). Saturday Night Live FAQ. New York: Applause Books. p. 2.

- Vesey, Alexandra (2013). "Live Music: Mediating Musical Performance and Discord on Saturday Night Live". In Marx, Nick; Sienkiewicz, Matt; Becker, Ron (eds.). Saturday Night Live and American TV. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01090-2. JSTOR j.ctt16gznsz.

- Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Irving; Wallace, Amy (1977). The Book of Lists. New York: Bantam Books (published 1978). ISBN 978-0-553-11150-7.