Marie Antoinette

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

Template:Infobox French Royalty

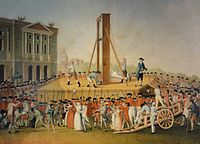

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna von Habsburg-Lothringen (November 2, 1755 – October 16, 1793), known to history as Marie Antoinette (pronounced /maʀi ɑ̃ntwanɛt/), was born an Archduchess of Austria and later became Queen of France and Navarre. At fourteen, she was married to Louis-Auguste, Dauphin of France, the future Louis XVI. She was the mother of Louis XVII, who died in the Temple Tower at the age of ten during the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette is perhaps best remembered for her legendary (and, some modern historians say, [specify] exaggerated) excesses and for her death: she was executed by guillotine at the height of the French Revolution in 1793 for the crime of treason although no evidence of such was proven. She has become one of the most famous queens in history.

Childhood: 1755–1767

Born at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, the Archduchess Maria Antonia was the youngest daughter of the head of the House of Habsburg, Maria Theresa of Austria, and the Holy Roman Emperor, Francis I. Maria Antonia was described as "a small, but completely healthy Archduchess."[1] Known at court as Madame Antoine, a French variation of her name, she was the fifteenth child born into the imperial family.

By many accounts, her childhood was somewhat complex. On the one hand, her parents had instituted several innovations in court life which made Austria one of the more progressive courts in Europe. While certain court functions remained formal by necessity, the Emperor and Empress nevertheless presided over many basic changes in court life. This included allowing relaxations in who could come to court (a change which allowed people of merit as well as birth to rise rapidly in the imperial favour), relatively lax dress etiquette, and the abolition of certain court protocols: for example the ritual where dozens of courtiers could be in the Empress' bedchamber, watching when she gave birth; the Empress disliked the ritual and would eject courtiers from her rooms whenever she went into labour.[2]

The laxity of court life was compounded by the "private" life which was developed by the Habsburgs, which was based within certain residences (mainly Schönbrunn Palace) that were almost entirely off-limits to the rest of the court. In their "private" life, the family could dress in bourgeois attire with no reproach, played games with "normal" (non-royal) children, had their schooling, and were treated to gardens and menageries. Marie would later attempt to "re-create" this atmosphere through her renovation of the Petit Trianon.[3]

While she had an idyllic "private" life, her initial role in the political arena – and in her mother's main aim of alliance through marriage – was relatively minuscule. As there were so many other children who could be married off, Antoine was sometimes neglected by her mother; as a result, Marie Antoinette later described her relationship with her mother as one of awe-inspired fear.[4] She also developed a mistrust of intelligent older women as a result of her mother's close relationship with her older sister, the Archduchess Maria Christina, who shared Maria Theresa's birthday and was her favorite child.[4] The lack of supervision also resulted in a sub-par education in many regards, and she could barely read or write properly in her native German by the time she was twelve.[5]

Marriage to Louis Auguste: 1767–1770

The events leading to her eventual betrothal to the Dauphin of France began in 1765, when Francis I died of a stroke in August of that year, leaving Maria Theresa to co-rule with her son and heir, the Emperor Joseph II.[6] By that time, marriage arrangements for several of Antoine's sisters had begun, with the Archduchess Maria Josepha betrothed to King Ferdinand of Naples, and Don Ferdinand of Parma tentatively set to marry one of the remaining eligible archduchesses. The purpose of these marriages was to cement the various complex alliances that Maria Theresa had entered into in the 1750s due to the Seven Years' War, which included Parma, Naples, Russia, and more importantly Austria's traditional enemy, France.[7] Without the Seven Years' War to "unite" the two countries briefly, the marriage of Antoine and the young Dauphin Louis-Auguste quite possibly might not have ever occurred.

In 1767, a smallpox outbreak hit the family. Antoine was one of the few who was immune to the disease due to already having had it at a young age. Emperor Joseph's wife, Maria Josepha, died first. Maria Theresa herself caught it and nearly died. Maria Theresa's daughter, Josepha then caught it from her sister-in-law (of the same name)'s improperly-sealed tomb, dying quickly afterwards; Archduchess Maria Elisabeth, another older sister, caught it, and, though she did not die, her looks were destroyed and she was rendered ineligible for marriage.[8] To compensate for the loss, Maria Theresa replaced Maria Josepha in the Naples marriage with another daughter, the Archduchess Maria Carolina. Finally, the Archduchess Maria Amalia, the eldest remaining sister eligible to wed, was then married to Don Ferdinand of Parma.[9]

This ultimately left twelve-year-old Antoine as the only potential bride left in the family for the fourteen-year-old Dauphin of France, Louis Auguste, who was also her second cousin once removed. Working painstakingly to process the marriage between the respective governments of France and Austria, the dowry was set at 200,000 crowns; portraits and rings were eventually exchanged as was custom.[10] Finally, Antoine was married by proxy on April 19, 1770, in the Church of the Augustine Friars; her brother Ferdinand stood in as the bridegroom. She was also officially restyled as Marie Antoinette, Dauphine of France.[11] Before leaving Maria Theresa reminded her of her duty to her home country; that she shouldn't forget she was Austrian, and thus had to promote the interests of Austria even as she was to be the future Queen of France. [citation needed]

Marie Antoinette was officially handed over to her French bearers on May 7, 1770, on an island on the Rhine River near Kehl. Chief among them were the comte and comtesse de Noailles, the latter who was appointed the Dauphine's Mistress of the Household by Louis XV of France.[12] She would meet him, Louis Auguste and the royal aunts (known as Mesdames Tantes), one week later. Before reaching Versailles, she would also meet her future brothers-in-law, Louis Stanislas Xavier, comte de Provence, and Charles Philippe, comte d'Artois, who would come to play important roles during and after her life.[13] Later, she met the rest of the family, including her betrothed's youngest sister, Madame Élisabeth, who at the end of Marie Antoinette's life would become her closest and most loyal friend.

The ceremonial wedding of the Dauphin and Dauphine took place on May 16, 1770, in the Palace of Versailles, after which was the ritual bedding.[14] It was assumed by custom that consummation of the marriage would take place on the wedding night. However, this did not occur, and the lack of consummation would plague the reputation of both the Dauphin and Dauphine for seven years.[15]

Life as dauphine: 1770–1774

The initial reaction to the marriage between Marie Antoinette and Louis Auguste was decidedly mixed. On the one hand, the Dauphine herself was popular among the people at large; her first official appearance in Paris on June 8, 1773 at the Tuileries was considered by many royal watchers a resounding success, with a reported 50,000 people crying out to see her. People were easily charmed by her personality and beauty. She was tall, and had fair skin, strawberry-blonde hair, and deep blue eyes. Her only flaw perhaps was her slight Habsburg lip, a feature she loathed. A visit to the opera for a court performance was also reported a success, with the Dauphine herself leading the applause. She was also widely commemorated for her acts of charity; in one incident, she personally attended to a dying man and arranged for his family to receive an income in his wake.[15]

At Court, however, the match was not so popular, due to the long-standing tensions between Austria and France, which had only so recently been mollified; many courtiers had been active at promoting a match with various Saxon princesses. Behind her back, Mesdames Tantes called Marie Antoinette l'Autrichienne, the "Austrian woman", from Autriche, French for "Austria". (Later on, on the eve of the Revolution, and as Marie Antoinette's unpopularity grew, l'Autrichienne was easily transformed into l'Autruchienne, a pun making use of the words autruche "ostrich" and chienne "bitch".)[16] Others accused her of trying to sway the king to Austria's thrall, destroying long-standing traditions (such as appointing people to posts due to friendship and not to peerage), and of laughing at the influence of older women at the royal court.[17] Many other courtiers, such as the comtesse du Barry, had a more or less tenuous relationship with the Dauphine.

However, Marie Antoinette's relationship with du Barry was one which was important to rectify, at least on the surface, as du Barry was the mistress of Louis XV, and thus not without considerable political influence over the king. In fact, she had been instrumental in the ousting from power of the duc de Choiseul, who had helped orchestrate the Franco-Austrian alliance as well as Marie Antoinette's own marriage. However, Louis XV's daughters, Mesdames Tantes, hated du Barry due to her unsavory relationship with their father. With manipulative coaching, the aunts encouraged the Dauphine to refuse to acknowledge the favorite, which was considered by some to be political blunder. After months of continued pressure from her mother and the Austrian minister, the comte de Mercy-Argenteau, Marie Antoinette grudgingly agreed to speak to du Barry on New Year's Day 1772. Although the limit of their conversation was Marie Antoinette's banal comment to the royal mistress that, "there are a lot of people at Versailles today", du Barry was satisfied and the crisis dissipated. Later, Marie Antoinette became more polite to the comtesse, pleasing Louis XV to no end.[18]

From the beginning, the Dauphine had to contend with constant letters from her mother, who wrote to her daughter regularly and who received secret reports from Mercy d'Argenteau on her daughter's behavior.[19] The Dauphine was constantly criticized for her inability to "inspire passion" in her husband, who rarely slept with her and had no interest in doing so, and was told again to promote the interests of Austria and the House of Lorraine, of which Marie Antoinette was a member through her late father. The Empress also criticized the Dauphine's pastime of horseback riding, though paradoxically the Empress's favorite portrait of her daughter was one of her in riding garb. The Empress would even go so far as to insult her daughter directly, telling her she was no longer pretty and had no talent, and was thus a failure, particularly after the marriages of the comte de Provence to Joséphine of Savoy and the comte d'Artois to Marie Thérèse of Savoy.[20]

To make up for the lack of affection from her husband and the endless criticism of her mother, Marie Antoinette began to spend more on gambling, with cards and horse-betting, as well as trips to the city and new clothing, shoes, pomade and rouge;[16] the purchase of which, while extravagant (causing her to go into debt) and somewhat neglectful of her royal duties (a portion of the Dauphine's allowance was supposed to go to charities), was not as much as critics accused her of spending. [citation needed] She was also expected by tradition to spend money on her attire, so as to outshine other women at Court, being the leading example of fashion in Versailles (the previous queen, Maria Leszczyńska, died in 1768, two years prior to Marie Antoinette's arrival).

Marie Antoinette also began to form deep friendships with various ladies in her retinue. Most noted were the sensitive and "pure" widow, the princesse de Lamballe, whom she appointed as Superintendent of her Household, and the fun-loving, down to Earth duchesse de Polignac, who would eventually form the cornerstone of the Queen's inner circle of friends (Société Particulière de la Reine).[17] Polignac later became the Royal Governess, and was liked as a friend by Louis. The closeness of the Dauphine's friendships with these ladies, influenced by various popular publications which promoted such friendships, would later cause accusations of lesbianism to be lodged against these women.[18] Others taken into her confidence at this time included her husband's brother, the comte d'Artois; her husband's youngest sister, Madame Elisabeth; her sister-in-law, the comtesse de Provence; and Christoph Willibald Gluck, her former music teacher, whom she took under her patronage upon his arrival in France.[19]

It was a week after the première of Gluck's opera, Iphigénie en Aulide, which had secured the Dauphine's position as a patron of the arts, that Louis XV began to fall ill on April 27, 1774. On May 4, the dying king sent comtesse du Barry away from Versailles; on May 10, at three in the afternoon, he died of smallpox at the age of sixty-four.[20]Marie Antoinette's husband was officially crowned as king Louis XVI of France on June 11, 1775 at Rheims Cathedral. Marie Antoinette was not crowned alongside him, instead merely accompanying him during the coronation ceremony.[21]

Reign: 1775–1793

1775–1778: The early years

From the outset, despite how she was portrayed in contemporary libelles, the new queen had very little political influence with her husband. Louis, who had been influenced as a child by anti-Austrian sentiments in the court, blocked many of her candidates, including Choiseul,[22] from taking important positions, aided and abetted by his two most important ministers, Chief Minister Maurepas and Foreign Minister Vergennes. All three were anti-Austrian, and were wary of the potential repercussions of allowing the queen – and, through her, the Austrian empire – to have any say in French policy.[23]

Marie Antoinette's situation became more precarious when, on August 6, 1775, her sister-in-law, the comtesse d'Artois, gave birth to a son, the duc d'Angoulême, who would be the presumptive heir to the French throne after his father and uncles for seven years. This resulted in a plethora of graphic satirical pamphlets (the libelles) being released, which mainly centered around the king's impotence and the queen's searching for sexual relief elsewhere, with men and women alike. Among her rumored lovers were her close friend, the princesse de Lamballe, and her handsome brother-in-law, the comte d'Artois, with whom the queen had a good rapport.[24]

This caused the queen to plunge further into the costly diversions of buying her dresses from Rose Bertin and gambling, simply to enjoy herself. On one famed occasion, she played for three days straight with players from Paris, straight up until her 21st birthday. She also began to attract various male admirers whom she accepted into her inner circles, including the baron de Besenval, the duc de Choigny, and Count Valentin Esterházy.[25]

She was given free rein to renovate the Petit Trianon, which was given to her as a gift by Louis XVI on August 27, 1775; she concentrated mainly on horticulture, redesigning the garden in the English mode. Though the castle was built in Louis XV's reign, the Petit Trianon became associated with Marie Antoinette's perceived extravagance. Rumors circulated that she plastered the walls with gold and diamonds.[26]

An even bigger problem, however, was the debt incurred by France during the Seven Years' War, still unpaid. It would be further exacerbated by Vergennes' prodding Louis XVI to get involved in Great Britain's war with its North American colonies, due to France's traditional rivalry with England.[27]

In the midst of preparations for sending aid to France, and in the atmosphere of first wave of libelles, Emperor Joseph came to call on his sister and brother-in-law on April 18, 1777, the subsequent six-week visit a part of the attempt to figure out why their marriage had not been consummated. It had been commonly believed that Louis XVI suffered from phimosis and needed corrective surgery. However, after talking to the king himself, Joseph was convinced that the king had "satisfactory" erections but that, upon introducing his "member", didn't stay inside long enough to ejaculate, having no clue as to what else he was supposed to do. As the emperor himself declared, if he had been given the chance to rectify the situation beforehand, Louis XVI "would have been whipped so that he ejaculated out of sheer rage like a donkey".[28]

It was due to Joseph's intervention that on August 30, 1777, that the marriage was officially consummated. Eight months later, in April, it was suspected that the queen was finally pregnant. This was confirmed on May 16, 1778.[29]

1778–1781: Motherhood and fashion

In the middle of her pregnancy, two events occurred which would impact the queen's later life. First, there was the return of the handsome Swede, Count Axel von Fersen, to Versailles for two years. Secondly, the king's wealthy but spiteful cousin, the duc de Chartres, was disgraced due to his questionable conduct during the Battle of Ouessant against the British. In addition, Marie Antoinette's brother, the Emperor Joseph, began making claims on the throne of Bavaria based upon his second marriage to the princess Maria Josepha of Bavaria. Marie Antoinette pleaded with her husband for the French to help intercede on behalf of Austria but was rebuffed by the king and his ministers. The Peace of Teschen, signed on May 13, 1779, would later end the brief conflict, but the incident once more showed the limited influence that the queen had in politics.[30]

Marie Antoinette's daughter, Marie Thérèse Charlotte, known more commonly by the traditional honorific of Madame Royale, was finally born at Versailles after a particularly difficult labor on December 19, 1778, following an ordeal where the queen literally collapsed from suffocation and hemorrhaging. The queen's bedroom was packed with courtiers watching the birth, and the doctor aiding her supposedly caused the excessive bleeding by accident. The windows had to be torn out to revive her. As a result of this harrowing experience, the queen banned most courtiers from entering her bedchamber for subsequent labors.[31]

The baby's paternity was contested in the libelles and most notably by the comte de Provence, who had always been open about his desire to replace his brother as king through various means. However, the child's paternity was never contested by the king himself, who was close to his daughter.[32]

The birth of a daughter meant that pressure to have a male heir continued, and Marie Antoinette wrote about her worrisome health, which might have contributed to a miscarriage in the summer of 1779.[33]

Meanwhile, the queen began to institute changes in the customs practiced at court, with the approval of the king. Some changes, such as the abolition of segregated dining spaces, had already been instituted for some time and had been met with disapproval from the older generation. More importantly was the abandonment of heavy make-up and the popular wide-hooped panniers for a more simple female look, typified first by the rustic robe à la polonaise and later by the simple muslin dress she wore in a 1783 Vigée-Le Brun portrait. She also began to participate in amateur plays and musicals, starting in 1780, in a theatre built for her and other courtiers who wished to indulge in the delights of acting and singing.[34]

In 1780, two candidates who had been supported by Marie Antoinette for positions, the marquis de Castries, and the comte de Ségur, were appointed Minister of the Navy and the Minister of War, respectively. Though many believed it was entirely the support of the queen that enabled them to secure their positions, in truth it was mostly the influence of Finance Minister Jacques Necker that got them the positions.[35]

Later that year, Empress Maria Theresa's health began to give way due to dropsy and an unnamed respiratory problem. She died on November 29, 1780, aged sixty-three in Vienna and was mourned throughout Europe. Though Marie Antoinette was worried that the death of her mother would jeopardize the Franco-Austrian alliance (as well as, ultimately, herself), Emperor Joseph reassured her through his own letters (as the empress had not stopped writing to Marie Antoinette until shortly before her death) that he had no intention of breaking the alliance.

Three months after the empress' death, it was rumored that Marie Antoinette was pregnant again, which was confirmed in March 1781. Another royal visit from Joseph II in July, partially to reaffirm the Franco-Austrian alliance and also a means of seeing his sister again, was tainted with rumors that Marie Antoinette was siphoning treasury money off to him, which were false.[36]

The queen gave birth to Louis Joseph Xavier François, who was given the title of duc de Bretagne, on October 22, 1781. The reaction to finally giving birth to an heir was best summed up by the words of Louis XVI himself, as he wrote them down in his hunting journal: "Madame, you have fulfilled our wishes and those of France, you are the mother of Dauphin".[37] He would, according to courtiers, try to frame sentences to put in the phrase "my son the Dauphin" in the weeks to come.[38] It also helped that, three days before the birth, the fighting in the conflict in America had been concluded with the surrender of General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.[39]

1782–1785: Declining popularity

Despite the general celebration over the birth of the Dauphin, Marie Antoinette's political influence, such as it was, did not increase to the benefit of Austria, as it had been hoped. Instead, after the death of the comte de Maurepas, the influence of Vergennes was strengthened, and she was again left out of political affairs. The same would happen during the so-called Kettle War, in which her brother Joseph attempted to open up the Scheldt River for naval passage. Later, another attempt by him to claim Bavaria was re-buffed as being against French interests.[40]

When accused of being a "dupe" by her brother for her political inaction, Marie Antoinette responded that she had little power. The king rarely talked to her about policy, and his anti-Austrian education as a child fortified his refusals in allowing his wife any participation in his decisions. As a result, she had to pretend to his ministers that she was in his full confidence in order to get the information she wanted. This led the court to believe she had more power than she did. As she wrote,"Would it be wise of me to have scenes with his (Louis XVI's) ministers over matters on which it is practically certain the King would not support me?".[41]

Marie Antoinette's temperament was more suited to her children, whose education and upbringing she personally directed. This was against the traditions of Versailles, where the queen usually had little say over the Enfants de France, as the royal children were called, and they were instead handed over to various courtiers who fought over the privilege. In particular, after the royal governess at the time of the Dauphin's birth, the princesse de Rohan-Guéméné, went bankrupt and was forced to resign, there was a controversy over who should replace her. Marie Antoinette appointed her favourite, the duchesse de Polignac, to the position. This met with disapproval from the court, as the duchess was considered to be of too "immodest" a birth to occupy such an exalted position. On the other hand, both the king and queen trusted Madame de Polignac completely, and the duchess had children of her own to whom the queen had become attached.[42]

In June 1783, Marie Antoinette was pregnant again. That same month, Count von Fersen returned from America, in order to secure a military appointment, and he was accepted into her private society. He would leave in September to become a captain of the bodyguard for his sovereign, Gustavus III, the Swedish king, who was conducting a tour of Europe. Marie Antoinette would suffer a miscarriage two months later, prompting more fears for her health.[43] Trying to calm her mind, during Fersen's first visit, and later after his return on June 7, 1784, the queen occupied herself with the creation of a "model village" near the Petit Trianon of a mill and twelve cottages, nine of which are still standing. This diversion, however, unexpectedly caused another uproar when the actual price of the Hameau was inflated by her critics. In truth, it was copied from another, far grander "model village" built for the prince de Condé. The comtesse de Provence's version even included windmills and a marble dairyhouse.[44]

Still seeking to fill her harried mind, Marie Antoinette became an avid reader of historical novels, and her scientific interest was piqued enough to become a witness to the launching of hot air balloons. She was fascinated by Rousseau's "back to nature" philosophy, as well as the culture of the Incas of Peru and their worship of the sun, which she had books about in her library. Briefly, she even sought out important British personages such as the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, and the British ambassador to France, the Duke of Dorset.[45] She also developed an interest in learning English, and while she never became fluent, she was able to write in broken English to her friend, the Duchess of Devonshire, who's life was very similar to her own.

Despite the many things which she did in her spare time, though, her primary concern became the health of the Dauphin, who was beginning to fail. By the time Fersen returned to Versailles in 1784, it was widely thought that the sickly Dauphin would not live to be an adult. As a consequence, it was rumored that the king and queen were attempting to have another child.[46] During this time, the play, The Marriage of Figaro, premiered in Paris. After initially having been banned by the king due to its negative portrayal of the nobility, the play was ironically finally allowed to be publicly performed because of its overwhelming popularity at court, where secret readings of it had been given.[47]

After Fersen's six week visit was over, the queen reported that she was pregnant in August. With the future enlargement of her family in mind, she bought the Château de Saint-Cloud, a place she had always loved, from the duc d'Orléans, the father of the previously disgraced duc de Chartres. She intended to leave it as an inheritance to her younger children without stipulation. This was a hugely unpopular acquisition, one which caused her unpopularity with certain factions of the nobility to greatly increase. This dislike soon began to spill out into the rest of France, as the idea of a French queen owning her own residence independent of the king was deemed shocking. Despite the baron de Breteuil working on her behalf, the sale did not help the public's frivolous image of the queen. The château's expensive price, almost 6 million livres, added with the substantial extra cost of redecorating it, ensured that there would be less money going towards repaying France's substantial debt.[48]

On March 27, 1785, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a second son, Louis Charles, who was created the duc de Normandie. Noticeably stronger than the sickly Dauphin, the new baby was affectionately nicknamed by the queen, my chou d'amour.[49] This naturally led to suspicions of illegitimacy once more. These suspicions along with the continued publication of the libelles, a never-ending cavalcade of court intrigues, the actions of Joseph II in the Kettle War, and her unwise purchase of Saint-Cloud combined to sharply turn popular opinion against the queen, and the image of a licentious, spendthrift, empty-headed foreign queen was fast taking root in the French psyche.[50]

1785–1786: The Affair of the Necklace

Several months after the birth of Louis Joseph, the queen received a letter from the famed jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge concerning a certain diamond necklace which the jewellers understood to have been purchased by the queen through the auspisces of the cardinal de Rohan. Marie Antoinette was shocked as she felt nothing but disdain for the cardinal. As the French ambassador to Vienna, he had flaunted libelles about her. Since his return to Paris in 1777, she had publicly snubbed him. Nor had she shown any interest towards the diamond necklace itself, which had originally been commissioned by Louis XV with the comtesse du Barry in mind. The necklace was an ostentatious piece, consisting of large diamonds arranged in an elaborate design of festoons, pendants and tassels. The queen had rejected the jewelers' offer to sell it to her on several occasions.[51]

It turned out that the gullible cardinal, desperate to get back in the queen's good graces, had been tricked into buying the necklace for the queen by Jeanne, comtesse de Lamotte-Valois, a con woman who herself had been snubbed by the queen in the past and who had become Rohan's mistress in 1783. Using papers forged by Rétaux de Villette, another of her lovers, Lamotte-Valois convinced the old cardinal that she was a close friend of the queen's and that she had been commissioned by her to help get the necklace through him. Deceived, Rohan met at Versailles with Nicole d'Olivia, who had been hired by Lamotte-Valois to impersonate the queen. From her, he received an order to buy the necklace so as to rectify Rohan's position. After the cardinal purchased the necklace, it was given to a "valet", who was in fact Jeanne's husband, who pried the gems from the necklace and sold them to the London jewelers Grey and Jeffries, where they were subsequently sold.[52]

Naturally, the payments for the necklace to Boehmer and Bassenge and Rohan (who apparently was to be paid back) were never made. This, combined with a revelation to one of the queen's ladies, Madame Campan, that the cardinal had bought the jewels and had used the forged signatures to do so, brought the arrest of the cardinal, Lamotte-Valois, de Villette, d'Olivia and several others thought to be remotely involved in the case. The case was brought before the Parlement de Paris, an unfortunate act which exposed the sordid claims of the defendants to the public. In Lamotte-Valois's brief, for example, it was claimed that the queen was sexually involved with the cardinal, and that the incident at Versailles was intended as a sexual tryst as well as a solicitation for the necklace. In addition, the situation was made worse because the Parlement had an axe to grind with the king, concerning his use of the despised lit de justice to limit its power.[53]

Partially out of revenge for what it saw as the king's unfair limitation of its power and partially as a response to the queen's supposed life of sin and waste, the Parlement acquitted the cardinal de Rohan on May 31, 1786 as an unsuspecting victim, though he was stripped of his titles and banished from court. The Lamottes were handed life imprisonments and were to be branded as thieves even though the comte de Lamotte was still in London at the time and had to be tried in absentia. Everyone else actually involved in the case was handed either a reprimand or had his property confiscated. Most of the blame for the incident, however, fell upon the shoulders of the queen herself. In spite of having never been involved in the purchase of the necklace, due to all the scandals that had surrounded her for years, the country chose to believe that the queen was lying. Her reputation never recovered from this blow.[53]

Amidst all of the negative attention focused on the trial, the queen turned thirty on November 2, 1785. She began to abandon some of the more frivolous clothing that she had favored in her youth for more dignified clothing. She started to gain weight. It turned out that she was pregnant once more, which she feared would affect her health, as she had only just given birth several months earlier. Ultimately, the stress of the "Affair of the Diamond Necklace" would cause her to go into labor. A second daughter, Sophie Hélène Béatrix, was born on July 9, 1786, several weeks premature. As the queen had feared, her health was affected by the pregnancy and she began to complain of shortness of breath soon afterwards.[54]

1786–June 1789: Real political influence

The continuing deterioration of the financial situation in France, though cutbacks in the royal retinue had been made, ultimately forced the king, in collaboration with his current Minister of Finance, Calonne, to call the Assembly of Notables, after an hiatus of 160 years. The assembly was held to try and pass some of the reforms needed to alleviate the financial situation when the Parlements refused to cooperate. The first meeting of the assembly took place on February 22, 1787, at which Marie Antoinette was not present. Later, her absence resulted in her being accused of trying to undermine the purpose of the assembly .[55]

However, the Assembly was a failure with or without the queen, as they did not pass any reforms and instead fell into a pattern of defying the king, demanding other reforms and for the acquiescence of the Parlements. As a result, the king dismissed Calonne on April 8, 1787; Vergennes died on February 13. The king, once more ignoring the queen's pro-Austrian candidate, appointed a childhood friend, the comte de Montmorin, to replace Vergennes as Foreign Minister.[56]

During this time, even as her candidate was rejected, the queen began to abandon her more carefree activities to become more involved in politics than ever before, and mostly against the interests of Austria. This was for a variety of reasons. First, her children were Enfants de France, and thus their future as leaders of France needed to be assured. Second, by concentrating on her children, the queen sought to improve the dissolute image she had acquired as result from the "Diamond Necklace Affair". Third, the king had begun to withdraw from a decision making role in government due to the onset of an acute case of depression from all the pressures he was under. The symptoms of this depression were passed off as drunkenness by the libelles. As a result, Marie Antoinette finally emerged as a politically viable entity, although that was never her actual intention. In her new capacity as a politician with a degree of power, the queen tried her best to help the situation brewing between the assembly and the king.[57]

This change in her political role signaled the beginning of the end of the influence of the duchesse de Polignac, as Marie Antoinette began to dislike the duchesse's huge expenditures and their impact on the finances of the Crown. The duchesse left for England in May, leaving her children behind in Versailles. Also in May, Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne, the archbishop of Toulouse and one of the queen's political allies, was appointed by the king to replace Calonne as the Finance Minister. He began instituting more cutbacks at court.[58]

Brienne, though, was not able to improve the financial situation. As her ally, this failure adversely affected the queen's political position. The continued poor financial climate of the country resulted in the Assembly of Notables being dissolved on May 25 because of its inability to get things done. This lack of solutions was wrongly blamed on the queen. In reality, the blame should have been placed on a combination of several other factors. There had been too many expensive wars, a too-large royal family whose large frivolous expenditures far exceeded those of the queen, and an unwillingness on the part of many of the aristocrats in charge to help defray the costs of the government out of their own pockets with higher taxes. Marie Antoinette earned her famous nickname of "Madame Déficit" in the summer of 1787 as a result of the public perception that she had single-handedly ruined the finances of the nation.[59]

The queen attempted to fight back with her own propaganda that portrayed her as caring mother, most notably with the portrait of her and her children done by Vigée-Lebrun, which premiered at the Royal Académie Salon de Paris in August 1787. This attack strategy was eventually dropped, however, because of the death of the queen's youngest child, Sophie. Around the same time, Jeanne de Lamotte-Valois escaped from prison in France and fled to London, where she published more damaging lies concerning her supposed "affair" with the queen.[60]

The political situation in 1787 began to worsen when Parlement was exiled and culminated on November 11, when the king tried to use a lit de justice to force through legislation. He was unexpectedly challenged by his formerly disgraced cousin, the duc de Chartres, who had inherited the title of duc d'Orléans at the recent death of his father. The new duc d'Orléans publicly protested the king's actions, and was subsequently exiled. The May Edicts issued on May 8, 1788, were also opposed by the public. Finally, on July 8 and August 8, the king announced his intention to bring back the Estates General, the traditional elected legislature of the country which had not been convened since 1614.[61]

Marie Antoinette was not directly involved with the exile of Parlement, the May Edicts or with the announcement regarding the Estates General. Her primary concern in late 1787 and 1788 was instead the improved health of the Dauphin. He was suffering from tuberculosis, which in his case had twisted and curved his spinal column severely. He was brought to the château at Meudon in the hope that its country air would help the young boy recover. Unfortunately, the move did little to alleviate the Dauphin's condition, which gradually continued to deteriorate.[62]

The queen, however, was present with her daughter, Madame Royale, when Tippu Sahib of Mysore visited Versailles seeking help against the British. More importantly she was instrumental in the recall of Jacques Necker as Finance Minister on August 26, a popular move, even though she herself was worried that the recall would again go against her if Necker was unsuccessful in reforming the country's finances.[62]

Her prediction began to come true when bread prices began to rise due to the severe 1788–1789 winter. The Dauphin's condition worsened even more, riots broke out in Paris in April, and on March 26, Louis XVI himself almost died from a fall off the roof.

"Come, Léonard, dress my hair, I must go like an actress, exhibit myself to a public that may hiss me", the queen quipped to her hairdresser as she prepared for the Mass celebrating the return of the Estates General on May 4, 1789. She knew that her rival, the duc d'Orléans, who had given money and bread to the people during the winter, would be popularly acclaimed by the crowd much to her detriment. The Estates General convened the next day.[63]

During the month of May, as the Estates General began to fracture between the democratic Third Estate, consisting of the bourgeoisie and radical nobility, and the royalist nobility of the Second Estate, while the king's brothers began to become more hardline. Despite these developments, the queen could only think about her son, the dying Dauphin, who finally passed away at Meudon, with the queen at his side, on June 4. His death, which would have normally been nationally mourned, was virtually ignored by the French people, who were instead preparing for the next meeting of the Estates General and a hopeful resolution to the bread crisis. As the Third Estate declared itself a National Assembly and took the Tennis Court Oath, and others listened to rumors that the queen wished to bathe in their blood, Marie Antoinette went into mourning for her eldest son.[64]

July 1789–1792: The French Revolution

The situation began to escalate violently in July as the National Assembly began to demand more rights, and Louis XVI began to push back with efforts to suppress the Third Estate. Then, on July 11, Necker was dismissed. Paris was besieged by riots at the news, which culminated in the famous Storming of the Bastille on July 14.[65]

In the weeks that followed, many of the most conservative, reactionary royalists, including the comte d'Artois and the duchesse de Polignac, fled France for fear of assassination. Marie Antoinette, whose life was the most in danger, stayed behind in order to help the king promote stability, even as his power was gradually being taken away by the National Constituent Assembly, which now ruled Paris and was conscripting men to serve in the Garde Nationale.[66]

By the end of August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (La Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen) was adopted, which officially created the beginning of a constitutional monarchy in France.[67] Despite this, the king was still required to perform certain court ceremonies, even as the situation in Paris became worse due to a bread shortage in September. The mob eventually forced the royal family, along with the comte de Provence, his wife and Madame Elisabeth, to move to Paris under the watchful eye of the Garde Nationale. In the city, the king and queen were installed in the Tuileries under lax house arrest.[68] During this limited house arrest, Marie Antoinette conveyed to her friends that she did not intend to involve herself any further in French politics, as everything, whether or not she was involved, would inevitably be attributed to her anyway and she feared the repercussions of further involvement.[69]

Despite the situation, Marie Antoinette was still required to perform charitable functions and certain religious ceremonies, which she did. Most of her time, however, was dedicated to her children once more.[70]

Despite her attempts to remain out of the public eye, she was falsely accused in the libelles of having an affair with the commander of the Garde Nationale, the marquis de La Fayette. In reality, she detested the marquis for his liberal tendencies and for being partially responsible for the royal family's earlier forced departure from Versailles.[71]

Constantly monitored by revolutionary spies within her own household, the queen played little or no part in the writing of the French Constitution of 1791, which greatly weakened the king's authority. She, nevertheless, hoped for a future where her son would still be able to rule, convinced that the violence would soon pass.[72]

During this time, there were many plots designed to help members of the royal family escape. The queen rejected several because she would not leave on her own without the king. Other opportunities to rescue the family were ultimately frittered away by the indecisive king. Once the king finally did commit to a plan, his indecision played an important role in its poor execution and ultimate failure. In an elaborate attempt to escape from Paris to the royalist stronghold of Montmédy planned by Count Axel von Fersen and the baron de Breteuil, some members of the royal family were to pose as the servants of a wealthy Russian baroness. Initially, the queen rejected the plan because it required her to leave with only her son. She wished instead for the rest of the royal family to accompany her. The king wasted a lot of time deciding upon which members of the family should be included in the venture, what the departure date should be, and the exact path of the route to be used. After many delays, the escape ultimately occurred on June 21, 1791, and was a failure. The entire family was captured twenty-four hours later at Varennes and taken back to Paris within a week.[73]

The result of the fiasco was a decline in the popularity of both the king and queen. The Jacobin Party successfully exploited the failed escape to advance its radical agenda. Its members called for the end to any type of monarchy in France.[74]

Though the new constitution was accepted on September 14, Marie Antoinette hoped through the end of 1791 that the distasteful political drift she saw occurring toward representative democracy could be stopped and rolled back. She fervently hoped that the constitution would prove unworkable, and also that her brother, the new Austrian emperor, Leopold II, would find some way to defeat the revolutionaries. However, she was unaware that Leopold was more interested in taking advantage of France's state of chaos for the benefit of Austria than in helping either his sister or her family.[75]

The result of Leopold's aggressive tendencies, and those of his son Francis II, who succeeded him in March, was that France declared war on Austria on April 20, 1792. This caused the queen to be viewed as an enemy, even though she was personally against Austrian claims on French lands. The situation became compounded in the summer when French armies were continually being defeated by the Austrians and the king was vetoing several measures that would have restricted his power even further. During this time, due to her husband's political activities, Marie-Antoinette received the nickname of "Madame Veto".[76]

On June 20, a mob broke into the Tuileries and demanded the king wear the tricolor to show his loyalty to France.[77] On July 31, the king's unpopularity was so great that the Legislative Assembly officially suspended his power with the words, "Louis XVI is no longer the King of the French".[78]

The vulnerability of the deposed king was exposed on August 10, when a clash between Swiss Guards and republican forces forced the royal family to take refuge with the Legislative Assembly. Several hundred Swiss Guards died in the fighting.[79] The royal family was imprisoned in the tower of the Temple in the Marais on August 13, under conditions considerably harsher than their previous confinement in the Tuileries.[80]

A week later, many of the royal family's attendants, among them the princesse de Lamballe, were taken in for interrogation by the Paris Commune. Transferred to the La Force prison, the princesse de Lamballe was one of the victims of the September Massacres, savagely killed on September 3, her head affixed on a pike that was marched around the city. Although Marie Antoinette did not see the head of her dear friend, it was paraded outside of her prison window. She fainted upon learning about the gruesome end that had befallen her former companion.[81]

On September 21, the monarchy was officially ended, and the National Convention was installed as the legal authority of France. The royal family was re-styled as the non-royal "Capets" Preparations for trying the king in a court of law began.[82]

Charged with undermining the First French Republic, Louis was separated from his family and tried in December. He was found guilty by the Convention, led by the Jacobins who rejected the idea of keeping him as a hostage. However, the sentence would not come until a month later, when he was condemned to execution by guillotine.[83]

1793: "Widow Capet" and death

Louis was executed on January 21, 1793, at the age of thirty-eight.[84] The result was that the "Widow Capet", as the former queen was called after the death of her husband, plunged into deep mourning; she refused to eat or take any exercise. Nor did she proclaim her son as Louis XVII, unlike the comte de Provence, who in exile proclaimed himself regent for the boy. Her health rapidly deteriorated in the following months. By this time she suffered from tuberculosis and possibly uterine cancer, which caused her to hemorrhage frequently.[85]

Despite her condition, the debate as to her fate was the central question of the National Convention after Louis's death. There were those who had been advocating her death for some time, while some had the idea of exchanging her for French prisoners of war or for a ransom from the Holy Roman Emperor. Thomas Paine advocated exile to America.[86] Starting in April, however, a Committee of Public Safety was formed, and men such as Jacques Hébert were beginning to call for Antoinette's trial; by the end of May, the Girondins had been chased out of power and arrested.[87] Other calls were made to "retrain" the Dauphin, to make him more pliant to revolutionary ideas. This was carried out when Louis Charles was separated from Antoinette on July 3, and given to the care of a cobbler.[87] On August 1, she herself was taken out of the Tower and entered into the Conciergerie as Prisoner No. 280.[88] Despite various attempts to get her out, such as the Carnation Plot in September, Marie Antoinette refused when the plots for her escape were brought to her attention.[89]

She was finally tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal on October 14. Unlike the king, who had been given time to prepare a defense, the queen's trial was far more of a sham, considering the time she was given (less than one day) and the Jacobin's misogynistic view of women in general. Among the things she was accused of (most, if not all, the accusations were untrue and probably lifted from rumors begun by libelles) included orchestrating orgies in Versailles, sending millions of livres of treasury money to Austria, plotting to kill the duc d'Orléans, incest with her son, declaring her son to be the new king of France and orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss Guards in 1792.

The most serious charge, however, was that she sexually abused her son. This was according to Louis Charles, who, through his coaching by Hébert and his guardian, accused his mother. The accusation caused Marie Antoinette to protest so emotionally that the women present in the courtroom – the market women who had stormed the palace for her entrails in 1789 – ironically also began to support her.[90] After being composed throughout the trial until this accusation was made, she said, "If I have not replied it is because Nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother." However, in reality the outcome of the trial had already been decided by the Committee of Public Safety around the time the Carnation Plot was uncovered, and she was declared guilty of treason in the early morning of October 16, after two days of proceedings.[91] She was executed later that day, at 12:15 pm – dressed as an ordinary French housewife – two and a half weeks before her thirty-eighth birthday.[92][93] Her body was thrown in an unmarked grave in the former La Madeleine cemetery (closed in 1794). Both her body and that of Louis XVI were exhumed on January 18, 1815. Proper Christian burial of the royal remains took place three days later, on January 21, in the necropolis of French Kings at St. Denis Basilica.[94]

Titles

- Her Imperial and Royal Highness Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria; Princess Maria Antonia of Hungary and Bohemia; Princess Maria Antonia of Tuscany (1755–1770)

- Her Royal Highness The Dauphine of France (1770–1774)

- Her Majesty The Queen of France and Navarre (1774–1791)

- Her Majesty The Queen of the French (1791–1792)

Legacy

As were many people and events involved with the French Revolution, Marie-Antoinette's life and role in the great social-political conflict were contingent upon many factors. Many have speculated as to how influential she actually was on the direction and nature that the revolution eventually took. In light of the varying contingencies surrounding her life that made her a hated and despised figure in the eyes of the revolutionaries, it is interesting to note that during her tenure as Queen of France, these factors caused her to be viewed as a genuine model of the old regime, perhaps even more so than her husband, the king. Due to her frivolous spending and indulgent royal lifestyle, as well as her well-known desire to benefit the Austrian empire with her legislation as queen, her caring, motherly nature was overshadowed, and revolutionaries only saw her as an obstruction to the Revolution.

The view on Marie Antoinette's role in French history has varied widely throughout the years. Even during her life, she was both a popular icon of goodness and a symbol of everything wrong with the French monarchy, the latter being a view that has persisted to this day far stronger than the former. However, there are some that would argue that the common historical perspective on Marie Antoinette is that she was yet another tragic victim of the radicalism of the Revolution, rather than a great symbol of French royal inadequacies. This view tends to sympathize with the plight of Marie Antoinette and her family and focus more on the documentation surrounding the last months, weeks, and days prior to her execution, where she is more clearly seen as Marie Antoinette the penitent, caring French mother rather than the defiant Queen of France.

Some contemporary sources, such as Mary Wollstonecraft[95] and Thomas Jefferson,[96] place the blame of the French Revolution and the subsequent Reign of Terror squarely on Marie Antoinette's shoulders; others, such as those who knew her (her lady-in-waiting Madame Campan and the royal governess, the Marquise de Tourzel, among them), focus more on her sweet character and considerable courage in the face of misunderstanding and adversity.[97] Immediately after her death, the picture painted by the libelles of the queen was generally held as the "correct" view of Marie Antoinette for many years, as the news of her execution was received with joy by the French populace, and the libelles themselves did not stop circulating even after her death.[98]

However, she was also considered to be a martyr by royalists both in and out of France, so much so that the Tower was demolished by Napoleon in order to get rid of all symbols of the oppression of the royal family.[99] The view of the queen as a martyr was a generally held view in the post-Napoleonic era and through the nineteenth century, though publications were still written (such as by the Goncourt brothers in the 1850s) portraying the queen as a frivolous spendthrift who single-handedly ruined France;[100] this view is not widely accepted as accurate by most modern historians, though it is important to note that even the less biased contemporary sources were quick to point out that the queen did have faults which contributed to her condition.

The end of the nineteenth century brought about some more changes in how the queen was viewed, particularly in light of the (heavily censored) publication of Count Axel Fersen's Journal intime by one of his descendants; theories about a torrid decade-long love affair between queen and count has become an area of debate since then. In particular, the popular theory is that Louis Charles, the second Dauphin (who would ultimately die at the age of 10 from maltreatment) was actually Fersen's child, and that the king was aware of it. Those who argue in favor of this theory point to the words of insiders who knew of the queen's alleged affair and the words of Fersen himself regarding the child's death, which indicate it to be a possibility.[101] Others argue that the queen had a liaison, but that it produced no child; others do not believe that an affair took place at all.[102]

The twentieth century brought about the recovery of some items that belonged to the queen, thought lost forever, as well as a wave of new biographies, which began to show the queen in a somewhat more sympathetic light; even those that were critical of the queen were more balanced than their eighteenth and nineteenth century predecessors. Public perception was also aided in the twentieth century with the advent of movies based upon biographies of the queen, the most famous of them including the Oscar-nominated 1938 Norma Shearer feature, Marie Antoinette, based upon the 1932 book Marie Antoinette by Stefan Zweig and the 2006 Kirsten Dunst feature based upon the 2001 book Marie Antoinette: The Journey by Lady Antonia Fraser. The latter author's book is considered, by some modern historians, as the most thorough and balanced biography of the queen, though it naturally builds upon earlier biographies, first hand accounts, and even the infamous libelles which destroyed the queen's reputation.

In fiction

The most famous historical fiction which features Marie Antoinette is the Alexandre Dumas, père novel Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (The Knight of the Red House,) which centers on the Carnation Plot. It is actually the first of a series of six books written by Dumas with Marie Antoinette featured, called the "Marie Antoinette novels", in which the queen is shown in a sympathetic light, particularly during the "Diamond Necklace Affair".

Some of the more famous historical novels that have portrayed Marie Antoinette in more recent years includes Carrolly Erickson's 2005 novel The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette, as well as Elena Maria Vidal's 1998 book Trianon. A 2000 book in the young adult Royal Diaries series is about Marie Antoinette's journey to France as a teenager.

The two best known movie portrayals of Marie Antoinette have been in the 1938 film directed by W. S. Van Dyke, in which the Norma Shearer played the queen, and the 2006 film directed by Sofia Coppola and starring Kirsten Dunst. The Affair of the Necklace was a 2001 film in which Hilary Swank played Jeanne de Saint-Remy de Valois and Joely Richardson played Marie Antoinette.

Marie Antoinette is also a central figure in the 1970s Japanese manga The Rose of Versailles/Lady Oscar by Riyoko Ikeda; she is a friend of the main character, Oscar François de Jarjayes. It also became an anime series in 1979.

In the supernatural manhwa series, Mana (manhwa), Mi-Ro, the ghost of a musician, concludes that Song Shi-ohn/Zion's "spiritual awakening" was caused by a past life. Shi-ohn then guesses that her past life was Marie Antoinette.

Ancestry

In film

| Date | Title | Director | Actress |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Marie Antoinette | W.S. Van Dyke | Norma Shearer |

| 1956 | Marie-Antoinette reine de France | Jean Delannoy | Michèle Morgan |

| 2001 | The Affair of the Necklace | Charles Shyer | Joely Richardson |

| 2006 | Marie Antoinette | Sofia Coppola | Kirsten Dunst |

Anecdotes

There are several popularly cited anecdotes from Marie Antoinette's life:

- Seven-year-old Mozart declared he would marry the Archduchess Maria Antonia upon seeing her during his performances at the Laxenburg Palace and Schönbrunn. There is little evidence that he ever said it, though it would have been in character for him; instead, it's documented that he leaped on Empress Maria Theresa's lap and demanded a kiss, which was given.[103]

- The queen was a drinker, much like her husband. While the king drank (though not as much as the libelles made out), the queen herself only rarely if ever drank, preferring instead to drink specially-ordered water from Ville d'Avray.[104]

- The queen pretended to be a milkmaid on her farm, and personally milked the cows. Most of the produce and dairy products at the Hameau de la Reine were produced at another farm. And, while the queen played peasant parts on stage, she was never known to personally have milked a cow.[105]

- The queen's breasts were used as casts for Sèvres cups made for the Hameau de la Reine to imitate Helen of Troy. This has never been verified by any reliable source.[106]

- When she was initially confronted by the poverty of the French people, the queen responded, "Qu’ils mangent de la brioche" ("Let them eat cake"). There are a variety of versions concerning the circumstances under which Marie Antoinette supposedly first said these words (ranging from peasants coming to the gates of Versailles begging for food to her driving through Paris and seeing the condition of the peasants on her own). However, the quote actually comes from the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who commented over twenty years before Marie Antoinette's birth that a "certain princess" said it, the supposed princess being Louis XIV's queen, Maria Theresa of Spain. Maria Theresa's quote was, "S'il ait aucun pain, donnez-leur la croûte au loin du pâté", which roughly translates to, "If there be no bread, give them the crust off of the pâté". Though this claim concerning the Spanish princess is also backed up by the comte de Provence, it is unknown if she, or any other French queen, actually ever said it.[107]

- Among the people who were charged by the libelles (wrongfully) of a sexual relation with the queen includes the princesse de Lamballe, the duchesse de Polignac, the comte d'Artois, the marquis de La Fayette and the baron de Luzon; ironically enough, the one man who may have had an affair with the queen (Fersen) was never targeted.

- Marie Antoinette personally instigated the "Affair of the Diamond Necklace", as she wished to oust the cardinal de Rohan from court. This is also untrue, as she had already successfully managed to shut the cardinal out of most court affairs with the king's cooperation (since the king also disliked Rohan personally), and hence had no reason to want to "destroy" the cardinal. In fact, the cardinal's social ostracism was so complete, the cardinal himself purchased the necklace in a desperate attempt to curry the queen's favor by attempting to give her a necklace she had previously rejected as being too expensive.[108]

- Marie Antoinette hated the Cardinal de Rohan because he raped her as a child when he was ambassador to Austria. The cardinal was not sent to Vienna as the French ambassador until 1772, two years after the queen left.[109]

- Marie Antoinette poisoned her first son in 1789 because she wanted her younger son with Fersen, Louis Charles, to eventually succeed to the French throne. This is unlikely due to the queen's documented concern for her children, though the paternity of Louis Charles has been disputed due to Fersen's closeness to the queen, as attested by his Journal intime and the testimony of others close to the queen. A sexual liaison at the time of the child's conception between the queen and Fersen seems to have been possible. However, it should be noted that the king himself never publicly disputed Louis Charles' paternity.[108]

- The queen stomped on a tricolor cockade in response to the Revolution at a dinner just prior to the March on Versailles. There is again no evidence that the queen actually did this, though it is true that she was highly suspicious of the Revolution and the motivations of its leaders.[110]

- Marie Antoinette declared her son the new king after Louis XVI was executed. There is no evidence that the queen, deeply in mourning, actually did this. However, many of the émigrés living abroad did, including the comte de Provence, who also proclaimed himself regent for the boy.[109]

Moberly-Jourdain incident

The Moberly-Jourdain incident, or the Ghosts of Petit Trianon or Versailles was an event that occurred on August 10, 1901 in the gardens of the Petit Trianon, involving two female academics, Charlotte Anne Moberly (1846-1937) and Eleanor Jourdain (1863-1924). The women were both from educated backgrounds; Moberly's father was a teacher and a bishop, and Jourdain's father was a vicar. During a trip to Versailles, they visited the Petit Trianon, a small chateau in the grounds of the Palace of Versailles, where they allegedly experienced a time slip, and saw Marie Antoinette as well as other people of the same period. After researching the history of the palace, and comparing notes of their experience, they published their work pseudonymously in a book entitled An Adventure, under the names of Elizabeth Morison and Frances Grant, in 1911. Their story of the event caused a sensation, and was subject to much ridicule.

Gallery

-

Hofburg Palace in Vienna, where Marie Antoinette was born

-

Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, where Marie Antoinette was raised mostly

-

Interior of the chapel of Versailles, where Marie Antoinette married Louis XVI

-

Marie Antoinette's official bedroom within the Palace of Versailles

-

The Hall of Mirrors, a place Marie Antoinette walked through probably almost everyday during her time at Versailles

-

The Petit Trianon, Marie Antoinette's preferred residence

-

Interior of the Petit Trianon; Marie Antoinette's true taste in furniture and decore is exemplified much more here than in the Palace of Versailles

-

One of the cottages built for Marie Antoinette in the Petit hameau

-

The Temple tower, where Marie Antoinette and her family were imprisoned after trying to flee the country, no longer stands

-

The Conciergerie, where Marie Antoinette was imprisoned during the last few months before her execution

-

Place de la Concorde, where Marie Antoinette was executed

-

Basilique Saint-Denis, where the remains of Marie Antoinette and her husband are buried, amongst those of the Monarchs of France

Notes

- ^ Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette. Anchor.

- ^ Fraser, 3, 13–18.

- ^ Fraser, 18.

- ^ a b Fraser, 22. Cite error: The named reference "antonia3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 31–33.

- ^ Fraser, 25.

- ^ Fraser, 10–12.

- ^ Fraser, 34.

- ^ Fraser, 27–30.

- ^ Fraser, 42–50.

- ^ Fraser, 51–53.

- ^ Fraser, 58–62.

- ^ Fraser, 64–69.

- ^ Fraser, 70–71.

- ^ a b Fraser, 157. Cite error: The named reference "antonia15" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 47. Cite error: The named reference "antonia16" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 94, 130–31. Cite error: The named reference "antonia17" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 87–90, 97–99. Cite error: The named reference "antonia18" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 80–81. Cite error: The named reference "antonia19" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 93–95. Cite error: The named reference "antonia20" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 132–137.

- ^ Fraser, 136–137.

- ^ Fraser, 124–127.

- ^ Fraser, 137–139.

- ^ Fraser, 140–145.

- ^ Fraser, 150–151.

- ^ Fraser, 152.

- ^ Fraser, 152–157.

- ^ Fraser, 160–162.

- ^ Fraser, 164–166.

- ^ Fraser, 166–170.

- ^ Fraser, 169.

- ^ Fraser, 172.

- ^ Fraser, 174–179.

- ^ Fraser, 183–184.

- ^ Fraser, 184–187.

- ^ Fraser, 187–188.

- ^ Fraser, 191.

- ^ Fraser, 194.

- ^ Fraser, 19–197.

- ^ Fraser, 197–198.

- ^ Fraser, 198–201.

- ^ Fraser, 202.

- ^ Fraser, 206–207.

- ^ Fraser, 208.

- ^ Fraser, 202.

- ^ Fraser, 214–215.

- ^ Fraser, 216–220.

- ^ Fraser, 224–225.

- ^ Fraser, 226.

- ^ Fraser, 226–228.

- ^ Fraser, 237–239.

- ^ a b Fraser, 239–242. Cite error: The named reference "antonia54" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 240, 244–245.

- ^ Fraser, 246–248.

- ^ Fraser, 248–250.

- ^ Fraser, 248–250.

- ^ Fraser, 250–255.

- ^ Fraser, 254–255.

- ^ Fraser, 255–258.

- ^ Fraser, 258–259.

- ^ a b Fraser, 260–261. Cite error: The named reference "antonia63" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 270–273.

- ^ Fraser, 274–278.

- ^ Fraser, 282–284.

- ^ Fraser, 284–289.

- ^ Fraser, 289.

- ^ Fraser, 298–304.

- ^ Fraser, 304.

- ^ Fraser, 304–308.

- ^ Fraser, 319.

- ^ Fraser, 320–321.

- ^ Fraser, 333–348.

- ^ Fraser, 350–352.

- ^ Fraser, 354–359.

- ^ Fraser, 365–368.

- ^ Fraser, 368.

- ^ Fraser, 372.

- ^ Fraser, 373–379.

- ^ Fraser, 382–386.

- ^ Fraser, 389.

- ^ Fraser, 392.

- ^ Fraser, 395–398.

- ^ Fraser, 399.

- ^ Fraser, 404–405, 408.

- ^ Fraser, 398, 408.

- ^ a b Fraser, 411–412. Cite error: The named reference "antonia89" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 414–415.

- ^ Fraser, 418.

- ^ Fraser, 429–435.

- ^ Fraser, 424–425, 436.

- ^ Fraser, 440.

- ^ The Times October 23, 1793, The Times.

- ^ Fraser, 411, 447.

- ^ Wollstonecraft, 33–35.

- ^ Fraser, 457–458.

- ^ Fraser, 129, 291.

- ^ Fraser, 442.

- ^ Fraser, 382.

- ^ Fraser, 455.

- ^ Hermann, chapter 6.

- ^ "Tea at Trianon". Elena Maria Vidal. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ Fraser, 19-20.

- ^ Fraser, 252.

- ^ Fraser, 206.

- ^ Fraser, 196.

- ^ Fraser, 135.

- ^ a b Fraser, 236. Cite error: The named reference "antonia105" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Fraser, 63. Cite error: The named reference "antonia107" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Fraser, 292–293.

References

- Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette, The Journey. Anchor. ISBN 0-7538-1305-X.

- Hermann, Eleanor (2006). Sex With The Queen. Harper/Morrow. ISBN 0-0608-4673-9.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary (1795). An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution and the Effect it Has Produced in Europe. St. Paul's.

Further reading

- Cronin, Vincent Louis and Antoinette. (1974) Collins. ISBN 0-8095-9216-9

- Lasky, KathrynThe Royal Diaries- Marie Antoinette, Princess of Versailles: Austria-France, 1769. (2000) Scholastic. ISBN 0-4390-7666-8

- Lever, Evelyne Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. (2000) St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-28333-4

- Loomis, Stanley The Fatal Friendship. (1972) Gyldendal. ISBN 0-931933-33-1

- Nasalund, Sera Jeter Abundance: A Novel of Marie Antoinette. (2006) Morrow. ISBN 0-0608-2539-1

- André Romijn Vive Madame la Dauphine – Book one of the Marie Antoinette Trilogy. (2008) ISBN 978-0955410024

- Thomas, Chantal The Wicked Queen: The Origins of the Myth of Marie-Antoinette. (1999) trans. by Julie Rose. Zone Books. 0-9422-9939-6

- Vidal, Elena Maria Trianon: A Novel of Royal France. (2000) Neumann Press ISBN 978-0911845969

- Weber, Caroline Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. (2006) Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-7949-1

See also

- Louis XVI of France

- Louis XVII of France

- Axel von Fersen, Jr.

- The French Revolution

- The Rose of Versailles

External links

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=2230 - Find A Grave

- Marie Antoinette - Marie Antoinette's official Versailles profile

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Marie-Antoinette

- Using mtDNA to track the case of Louis XVII, son of Marie Antoinette

- Marie Antoinette Online - A site with a sympathetic bend, and contains a great deal of information.

- Tea At Trianon - Many articles on all things Antoinette, from Versailles to Trianon to the most obscure details of life in Royal France, by historian and author Elena Maria Vidal.

- Marie Antoinette (2006) - Official movie site for the Sofia Coppola picture.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Marie Antoinette" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Online catalog of Marie Antoinette's personal reading library from the Petit-Trianon palace, based on 1863 printed catalog, online at LibraryThing.

- [1] How the revolutionaries maligned Marie Antoinette and manipulated public perception ---go to Cookbook.

Marie Antoinette Born: 2 November 1755 Died: 16 October 1793 | ||

| French royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Marie-Josèphe of Saxony |

Dauphine of France 16 May 1770 – 10 May 1774 |

Vacant Title next held by Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte of France |

| Vacant Title last held by Maria Leszczyńska |

Queen consort of France and Navarre 10 May 1774 – 1 October 1791 |

Vacant Title next held by Joséphine de Beauharnaisas Empress of the French |

| Queen consort of the French 1 October 1791 – 21 September 1792 | ||

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Loss of title |

— TITULAR — Queen consort of France and Navarre/ Queen consort of the French 1 October 1791 – 21 January 1793 |

Vacant Title next held by Marie Josephine Louise of Savoy |