1947 Jammu massacres

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

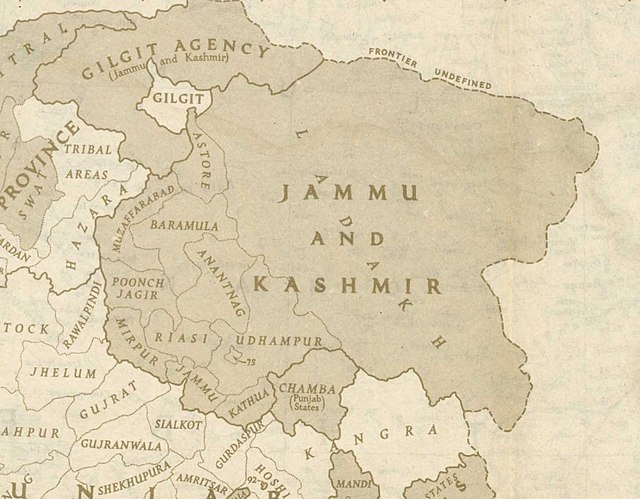

After the Partition of India, during September–November 1947 in the Jammu region of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, a large number of Muslims were massacred and others driven away to West Punjab. The killings were carried out by extremist Hindus and Sikhs, aided and abetted by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the Maharaja Hari Singh.[6] The riots were planned and executed by the activists of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).[7][8]

| 1947 Jammu massacres | |

|---|---|

| Date | September 1947 - November 1947 |

| Location | |

| Goals | Genocide, Ethnic cleansing. |

| Methods | Rioting, pogrom, arson, mass rape |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 20,000–100,000 Muslims[1][2] 20,000+ Hindus and Sikhs[3][4][5] |

An early official calculation made in Pakistan, using headcount data, estimated 50,000 Muslims killed.[9] A team of two Englishmen jointly commissioned by the governments of India and Pakistan investigated seven major incidents of violence between 20 October – 9 November 1947, estimating 70,000 deaths.[10] Scholar Ian Copland estimated total deaths to be around 80,000,[11] while Jammu journalist Ved Bhasin estimated them to be around 100,000.[12] Scholar Christopher Snedden says, the number of Muslims killed were between 20,000 and 100,000.[1]

Much higher figures were reported by newspapers at that time. A report by a special correspondent of The Times, published on 10 August 1948, stated that a total of 237,000 Muslims were either killed or migrated to Pakistan.[6][a] The editor of The Statesman Ian Stephens claimed that 500,000 Muslims, "the entire Muslim element of the population", was eliminated and 200,000 "just disappeared".[15] Scholar Ian Copland finds these figures dubious.[b]

As a result of the killings, scholar Ilyas Chattha says, more than 100,000 Jammu refugees had arrived in Sialkot in Pakistan.[16] Snedden, on the other hand, cites a "comprehensive report" in Dawn published in January 1951, which said that 200,000 Muslims went as refugees to Pakistan in October–November 1947.[3] An unidentified organisation in Pakistan counted refugees from Jammu and Kashmir during May–July 1949, and found 333,964 refugees from the Indian-held parts of the state.[17]

Observers state that Hari Singh’s aim was to alter the demographics of the region by eliminating the Muslim population, in order to ensure a Hindu majority in the region.[18][19]

Subsequently, many non-Muslims, estimated as over 20,000, were also massacred by Pakistani tribesmen and soldiers, in the Mirpur region of today's Azad Kashmir.[3][4][5]

Background

At the time of the Partition of India in 1947, the British abandoned their suzerainty over the princely states, which were left with the options of joining India or Pakistan or remaining independent. Hari Singh, the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, the Maharaja indicated his preference to remain independent of the new dominions. All the major political groups of the state supported the Maharaja's decision, except for the Muslim Conference, which declared in favour of accession to Pakistan on 19 July 1947.[20] The Muslim Conference was popular in the Jammu province of the state. It was closely allied with the All-India Muslim League, which was set to inherit Pakistan.

Unlike the Kashmir valley which remained mostly calm during this transition period, the Jammu province which was contiguous to Punjab, experienced mass migration that led to violent inter-religious activity. Large numbers of Hindus and Sikhs from Rawalpindi and Sialkot started arriving since March 1947, bringing "harrowing stories of Muslim atrocities in West Punjab". This provoked counter-violence on Jammu Muslims, which had "many parallels with that in Sialkot".[19] Ilyas Chattha writes, "the Kashmiri Muslims were to pay a heavy price in September–October 1947 for the earlier violence of West Punjab."[21]

According to scholar Ian Copland, the administration's pogrom against its Muslim subjects in Jammu was undertaken partly out of revenge for the Poonch rebellion that started earlier.[22]

Scholar Ilyas Chattha and Ved Bhasin blame the mishandling of law and order by Maharaja Hari Singh and his armed forces in the whole Jammu province, for the large scale communal violence in the region.[19][7]

Violence in Jammu

There were reports of large-scale massacres of Muslims in Udhampur district, particularly in proper Udhampur, Chenani, Ramnagar, Bhaderwah and Reasi areas. Killing of a large number of Muslims was reported from Chhamb, Deva Batala, Manawsar and other parts of Akhnoor with many people fleeing to Pakistan or moving to Jammu. In Kathua district and Bilawar area, there was extensive killing of Muslims with women raped and abducted.[7][12]

There was mass killing of Muslims in and around Jammu. The state troops led the attacks. The state officials provided arms and ammunition to the rioters. The administration had demobilised a large number of Muslim soldiers in the state army and had discharged Muslim police officers.[23][c] Most of the Muslims outside the Muslim dominated areas were killed by the communal rioters who moved in vehicles with arms and ammunition, though the city was officially put under curfew. Many number of Gujjar men and women who used to supply milk to the city from the surrounding villages were reportedly massacred en-route. It is said that the Ramnagar reserve in Jammu was littered with the dead bodies of Gujjar men, women and children. In the Muslim localities of Jammu city, Talab Khatikan and Mohalla Ustad, Muslims were surrounded and were denied water supply and food. The Muslims in Talab Khatikan area had joined to defend themselves with the arms they could gather, who later received support from the Muslim Conference. They were eventually asked to surrender and the administration asked them to go to Pakistan for their safety. These people, in thousands, were loaded in numerous trucks and were escorted by the troops. When they reached the outskirts of the city, they were reportedly pulled out and killed by armed people, while abducting the women.[25][7]

On November 16, 1947, Sheikh Abdullah arrived in Jammu and a refugee camp was set up in Mohalla Ustad.[7]

Observations

— Ved Bhasin, who witnessed the Jammu violence in 1947.[7]

Mahatma Gandhi commented on the situation in Jammu on 25 December 1947 in his speech at a prayer meeting in New Delhi: "The Hindus and Sikhs of Jammu and those who had gone there from outside killed Muslims. The Maharaja of Kashmir is responsible for what is happening there…A large number of Muslims have been killed there and Muslim women have been dishonoured."[26]

According to Ved Bhasin and Chattha, the Jammu riots were "clearly" planned and executed by members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh(RSS) who were joined by the refugees from West Pakistan, and were supported strongly by Hari Singh and his administration.[7][8]

Bhasin says that the massacres took place in the presence of the then Jammu and Kashmir's Prime Minister Mehr Chand Mahajan and the governor of Jammu, Lala Chet Ram Chopra, and that some of those who led these riots in Udhampur and Bhaderwah later joined the National Conference with some of them also serving as ministers.[7][d]

Aftermath

On October 24, after Poonch rebellion, a provisional government of Azad Kashmir was established at Palandri under the leadership of Sardar Ibrahim.

Meanwhile, several thousand Pashtun tribesmen from North-West Frontier Province, who had support from Pakistani administration, had been pouring into Jammu and Kashmir to liberate it from the Maharaja's rule.

Many Hindus and Sikhs, on and after 25 November 1947 gathered in Mirpur for shelter and protection were killed by the Pakistani troops and tribesmen.[4][27] A 'greatly shocked' Sardar Ibrahim painfully confirmed that Hindus were 'disposed of' in Mirpur in November 1947, although he does not mention any figures.[3][e][f]

Population figures

The table below compares the 1941 percentage of Muslim population with the present percentage for the Indian-controlled part of the Jammu province and gives figures for estimated 'loss' of Muslims, due to deaths as well as migration.

| Region | 1941 Population[29] | 1941 Muslim proportion[29] | 2011 Muslim proportion[30] | Loss of Muslims (est)[g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jammu District[h] | 431,362 | 39.6% | 7.1% | 151,010 |

| Kathua District | 177,672 | 25.3% | 10.4% | 29,567 |

| Udhampur District (inc. Chenani)[i] | 306,013 | 42.7% | 41.5% | 5,975 |

| Reasi District[j] | 257,903 | 68.1% | 58.4% | 59,804 |

| Jammu province (exc. Poonch) | 1,172,950 | 44.5% | 27.9% | 246,356 |

| Poonch District | 421,828 | 90.0% | 90.4% | – |

Scholar Ian Copland tries to estimate how many Muslims might have been killed in the Jammu violence based on the demographic data. If the headcount figure of 333,964 refugees from the Indian-held parts of the state[17] is used to calculate how many Muslims might have been killed in Jammu, one ends up with a surplus rather than a deficit.[11][k] The State's Army Chief, Henry Lawrence Scott, has stated that at least 100,000 Muslim refugees of East Punjab were safely escorted on their way to Pakistan through Jammu and Kashmir in 1947.[32] To get a rough idea, if we assume that the first figure of 333,964 included the approximately 100,000 East Punjab refugees, we can estimate the number of Jammu Muslims killed to be a few tens of thousands.

Notes

- ^ To quote the 10 August 1948 report published in The Times:

The number of 237,000 was out of 411,000 Muslims said to have lived in the 'eastern Jammu' province. No calculations for the exact figure were given and the figure was not broken down into deaths and escapes. The 'Special Correspondent' that authored the report is later identified as Frederick Paul Mainprice, the former Assistant Political Agent of the Gilgit Agency, who worked as a Deputy Secretary for the Pakistan government during 1948–49 "specialising on the Kashmir problem".[13][14]"237,000 Muslims were systematically exterminated – unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border – by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the Maharaja in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs. This happened in October 1947, five days before the Pathan invasion and nine days before the Maharaja’s accession to India."

- ^ Copland, State, Community and Neighbourhood 2005, p. 153: "None of these figures, however, are authoritative.... And the Times man, too, seems to have harboured Pakistani sympathies and, more importantly, offers no clues as to the source of his information."

- ^ According to the accounts of refugees, "the Maharaja himself toured about the villages with truck-loads of arms and ammunition following him, and personally held consultations with the local officials, distributed arms, and in some cases fired the first shot."[24]

- ^ Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, Kashmir Life: Another incident that I recall is about Mr Mehr Chand Mahajan who told a delegation of Hindus who met him in the palace when he arrived in Jammu that now when the power is being transferred to the people they should better demand parity. When one of them associated with National Conference asked how can they demand parity when there is so much difference in population ratio. Pointing to the Ramnagar rakh below, where some bodies of Muslims were still lying he said “the population ratio too can change”. ...Mahajan later became a finance and revenue minister in Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s ministry.

- ^ Ibrahim Khan, Muhammad (1990), The Kashmir Saga, Verinag, p. 55: During the month of November, 1947, I went to Mirpur to see things there for myself. I visited, during the night, one Hindu refugee camp at Ali Baig—about 15 miles from Mirpur proper. Among the refugees I found some of my fellow lawyers in a pathetic condition. I saw them myself, sympathised with them and solemnly promised that they would be rescued and sent to Pakistan, from where they would eventually be sent out to India.... After a couple of days, when I visited the camp again to do my bit for them, I was greatly shocked to learn that all those people whom I had seen on the last occasion had been disposed of. I can only say that nothing in my life pained my conscience so much as did this incident.... Those who were in charge of those camps were duly dealt with but that certainly is no compensation to those whose near and dear ones were killed.

- ^ According to a survivor, the prison guard at Ali Baig, who killed his victims with a butcher's knife chanting kalima, identified himself to Sardar Ibrahim as a soldier of Pakistan and a follower of Mohammad Ali Jinnah and said that he was following the orders of his superiors.[28]

- ^ These figures are notional. They represent the number of Muslims lost to the state, due to either deaths or out-migration, so that the 2011 demographic percentage could have been obtained. It is derived by multiplying the 1941 population figure by the factor (1941 percentage – 2011 percentage)/(100 – 2011 percentage). If there was in-migration of Muslims or if the Muslim population grew at faster rate than the rest, these figures would be underestimates. If there was in-migration of non-Muslims, these figures would be overestimates.

- ^ The 1947 Jammu district is now divided into Jammu and Samba districts

- ^ The 1947 Udhampur district is now divided into Ramban, Udhampur, Doda and Kishtwar districts

- ^ The 1947 Reasi district is now divided into Reasi and Rajouri districts

- ^ An even higher figure of 500,000 Muslim refugees was reported in Dawn on 2 January 1951.[17] Scholar Ilyas Chattha has claimed that over 1 million Muslims were uprooted owing to the violence.[31] Evidently, such high figures are not supported by the demographic data.

See also

References

- ^ a b Snedden, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris 2015, p. 167.

- ^ Khalid Bashir Ahmad. "circa 1947: A Long Story". www.kashmirlife.net. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Das Gupta, Jammu and Kashmir 2012, p. 97.

- ^ a b Hasan, Mirpur 1947 (2013)

- ^ a b Snedden, What happened to Muslims in Jammu? 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Jammu 1947 by Ved Bhasin".

- ^ a b Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 182, 183.

- ^ Copland, State, Community and Neighbourhood 2005, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Copland, State, Community and Neighbourhood 2005, p. 153.

- ^ a b Ahmad, Khalid Bashir (5 November 2014), "circa 1947: A Long Story", Kashmir Life, retrieved 11 October 2016

- ^ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 55, 330.

- ^ MAINPRICE PAPERS, South Asian Studies Archive, University of Cambridge, retrieved 31 March 2017

- ^ Snedden, What happened to Muslims in Jammu? 2001, p. 121.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Snedden, What happened to Muslims in Jammu? 2001, p. 125.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 179, 183.

- ^ a b c Noorani, A.G. (25 February 2012). "Horrors of Partition". Frontline. Vol. 29, no. 04.

- ^ Puri, Balraj (November 2010), "The Question of Accession", Epilogue, 4 (11): 4–6,

Eventually they agreed on a modified resolution which 'respectfully and fervently appealed to the Maharaja Bahadur to declare internal autonomy of the State... and accede to the Dominion of Pakistan... However, the General Council did not challenge the maharaja's right to take a decision on accession, and it acknowledged that his rights should be protected even after acceding to Pakistan.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 179.

- ^ State, Community and Neighbourhood in Princely North India, c. 1900-1950 By I. Copland. Palgrave Macmillan. 2005. p. 143.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 180, 182.

- ^ Bakshi, S. R. Kashmir Through Ages (5 Vol). Sarup & Sons. p. 270. ISBN 9788185431710.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 183.

- ^ "Document Twenty". The second assassination of Gandhi? by Ram Puniyani. Anamika Pub & Distributors. 2003. pp. 91, 92.

- ^ Sharma 2013, p. 139.

- ^ Bhagotra 2013, p. 124.

- ^ a b Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 28.

- ^ 2011 Census India: Population by religious community

- ^ Chattha, Ilyas (2016), "The Long Shadow of 1947: Partition, Violence and Displacement in Jammu & Kashmir", in Amritjit Singh; Nalini Iyer; Rahul K. Gairola (eds.), Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics, Lexington Books, pp. 143–156, ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4

- ^ Ankit, Henry Scott 2010, p. 48.

Bibliography

- Rakesh Ankit (May 2010). "Henry Scott: The forgotten soldier of Kashmir". Epilogue. 4 (5): 44–49.

- Chattha, Ilyas (2011), Partition and Locality: Violence, Migration and Development in Gujranwala and Sialkot 1947-1961, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199061723

- Chattha, Ilyas Ahmad (September 2009), Partition and Its Aftermath: Violence, Migration and the Role of Refugees in the Socio-Economic Development of Gujranwala and Sialkot Cities, 1947-1961, University of Southampton, retrieved 16 February 2016

- Copland, Ian (2005). State, Community and Neighbourhood in Princely North India, c. 1900-1950. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-230-00598-3.

- Das Gupta, Jyoti Bhusan (2012) [first published 1968], Jammu and Kashmir, Springer, ISBN 978-94-011-9231-6

- Gupta, Bal K. (2013), Forgotten Atrocities: Memoirs of a Survivor of the 1947 Partition of India, Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1-257-91419-7

- Bhagotra, R. K. (2013) [first published in The Tawi Deepika, 1987], "Escape from Death Seven Times", Ibid, pp. 123–125

- Hasan, Khalid (2013) [first published in Friday Times, 2007], "Mirpur 1947", Ibid, pp. 141–144

- Sharma, Ram Chander (2013) [first published in Daily Excelsior, date unknown], "Mirpur – Forgotten City", Ibid, pp. 138–140

- Snedden, Christopher (2001), "What happened to Muslims in Jammu? Local identity, '"the massacre" of 1947' and the roots of the 'Kashmir problem'", South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 24 (2): 111–134, doi:10.1080/00856400108723454

- Snedden, Christopher (2013) [first published as The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir, 2012], Kashmir: The Unwritten History, HarperCollins India, ISBN 9350298988

- Snedden, Christopher (2015), Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-1-84904-342-7

External links

- Khalid Bashir Ahmad, Jammu 1947: Tales of Bloodshed, Greater Kashmir, Nov 5 2014.