Creatine: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Line 86:

}}

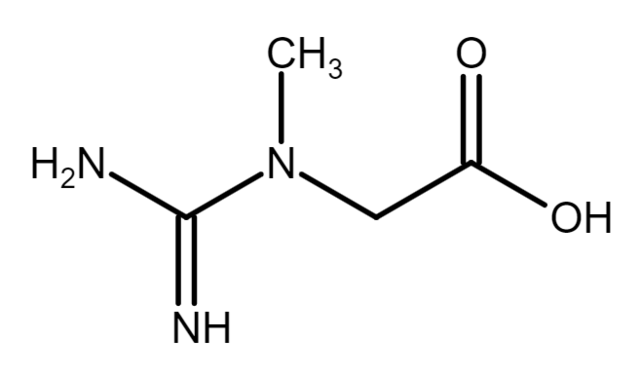

'''Creatine''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|r|iː|ə|t|iː|n}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|r|iː|ə|t|ɪ|n}})<ref>{{cite book|title=Essentials of Creatine in Sports and Health | veditors = Stout JR, Antonio J, Kalman E |year=2008|publisher=Humana|isbn=978-1-59745-573-2}}</ref> is an [[organic compound]] with the nominal formula {{chem2|(H2N)(HN)CN(CH3)CH2CO2H}}. It exists in various [[tautomer]]s in solutions (among which are neutral form and various [[zwitterionic]] forms). Creatine is found in [[vertebrate]]s, where it facilitates recycling of [[adenosine triphosphate]] (ATP), primarily in [[muscle]] and [[brain]] tissue. Recycling is achieved by converting [[adenosine diphosphate]] (ADP) back to ATP via donation of [[phosphate group]]s. Creatine also acts as a [[Buffer solution|buffer]].<ref name="pmid26202197">{{cite journal | vauthors = Barcelos RP, Stefanello ST, Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Soares FA | title = Creatine and the Liver: Metabolism and Possible Interactions | journal = Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 12–8 | year = 2016 | pmid = 26202197 | doi = 10.2174/1389557515666150722102613 | quote = The process of creatine synthesis occurs in two steps, catalyzed by L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) and guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase (GAMT), which take place mainly in kidney and liver, respectively. This molecule plays an important energy/pH buffer function in tissues, and to guarantee the maintenance of its total body pool, the lost creatine must be replaced from diet or de novo synthesis. }}</ref>

==History==

Line 95:

The discovery of phosphocreatine<ref>{{cite book | last = Saks | first = Valdur | name-list-style = vanc | year = 2007 | title = Molecular system bioenergetics: energy for life | url = https://archive.org/details/molecularsystemb00saks | url-access = limited | place = Weinheim | publisher = Wiley-VCH | page = [https://archive.org/details/molecularsystemb00saks/page/n31 2] | isbn = 978-3-527-31787-5 }}</ref><ref name="ochoa">{{cite book | last = Ochoa | first = Severo | name-list-style = vanc | year = 1989 | editor-last = Sherman | editor-first = E. J. | editor2-last = National Academy of Sciences | title = David Nachmansohn | series = Biographical Memoirs | publisher = National Academies Press | volume = 58 | pages = 357–404 | isbn = 978-0-309-03938-3 }}</ref> was reported in 1927.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Eggleton P, Eggleton GP | title = The Inorganic Phosphate and a Labile Form of Organic Phosphate in the Gastrocnemius of the Frog | journal = The Biochemical Journal | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | pages = 190–5 | year = 1927 | pmid = 16743804 | pmc = 1251888 | doi = 10.1042/bj0210190 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fiske CH, Subbarow Y | title = The nature of the 'inorganic phosphate' in voluntary muscle | journal = Science | volume = 65 | issue = 1686 | pages = 401–3 | date = April 1927 | pmid = 17807679 | doi = 10.1126/science.65.1686.401 | bibcode = 1927Sci....65..401F }}</ref><ref name=ochoa/> In the 1960s, creatine kinase (CK) was shown to phosphorylate ADP using phosphocreatine (PCr) to generate ATP. It follows that ATP - not PCr - is directly consumed in muscle contraction. CK uses creatine to "buffer" the ATP/ADP ratio.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Wallimann T |chapter=Introduction – Creatine: Cheap Ergogenic Supplement with Great Potential for Health and Disease | veditors = Salomons GS, Wyss M |title=Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease | url = https://archive.org/details/creatinecreatine00salo | url-access = limited |pages=[https://archive.org/details/creatinecreatine00salo/page/n16 1]–16 |year=2007 |isbn=978-1-4020-6486-9 |publisher=Springer }}</ref>

While creatine's influence on physical performance has been well documented since the early twentieth century, it came into public view following the [[1992 Summer Olympics|1992 Olympics]] in [[Barcelona]]. An August 7, 1992 article in ''[[The Times]]'' reported that [[Linford Christie]], the gold medal winner at 100 meters, had used creatine before the Olympics (however, it should also be mentionednoted that Linford Christie was found guilty of doping later in his career.).<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/athletics/4768790/Shadow-over-Christies-reputation.html | title=Shadow over Christie's reputation | date=22 August 2000 }}</ref> An article in ''Bodybuilding Monthly'' named [[Sally Gunnell]], who was the gold medalist in the 400-meter hurdles, as another creatine user. In addition, ''The Times'' also noted that 100 meter hurdler [[Colin Jackson]] began taking creatine before the Olympics.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalreviewofmedicine.com/issue/2004_07_30/feature07_14.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061116021537/http://www.nationalreviewofmedicine.com/issue/2004_07_30/feature07_14.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=2006-11-16 |title=Supplement muscles in on the market |publisher=National Review of Medicine |date=2004-07-30 |access-date=2011-05-25 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Creatine |last=Passwater |first=Richard A. |name-list-style=vanc |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-87983-868-3 |page=9 |publisher=McGraw Hill Professional |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=umy67wOLOckC |access-date=8 May 2018 |archive-date=19 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220619121759/https://books.google.com/books?id=umy67wOLOckC |url-status=live }}</ref>

[[image:Phosphocreatine.svg|thumb|left|[[Phosphocreatine]] relays phosphate to ADP.]]

Line 116:

===Genetic deficiencies===

Genetic deficiencies in the creatine biosynthetic pathway lead to various [[cerebral creatine deficiency|severe neurological defects]].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=602360 |title=L-Arginine:Glycine Amidinotransferase |access-date=16 August 2010 |archive-date=24 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130824195046/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=602360 |url-status=live }}</ref> Clinically, there are three distinct disorders of creatine metabolism, termed [[Cerebral creatine deficiency|cerebral creatine deficiencies]]. Deficiencies in the two synthesis enzymes can cause [[Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase|L-arginine:glycine amidinotransferase deficiency]] caused by variants in ''[[GATM (gene)|GATM]]'' and [[guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency]], caused by variants in ''[[GAMT]]''. Both biosynthetic defects are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. A third defect, [[creatine transporter defect]], is caused by mutations in ''[[SLC6A8]]'' and is inherited in a X-linked manner. This condition is related to the transport of creatine into the brain.<ref name="creatinedefects">{{cite journal | vauthors = Braissant O, Henry H, Béard E, Uldry J | title = Creatine deficiency syndromes and the importance of creatine synthesis in the brain | journal = Amino Acids | volume = 40 | issue = 5 | pages = 1315–24 | date = May 2011 | pmid = 21390529 | doi = 10.1007/s00726-011-0852-z | s2cid = 13755292 | url = https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_CE3937F9A69E.P001/REF.pdf | access-date = 8 July 2019 | archive-date = 10 March 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210310001947/https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_CE3937F9A69E.P001/REF.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref>

===Vegetarians===

Some studies suggest that total muscle creatine is significantly lower in vegetarians than non-vegetarians.<ref name="burke">{{cite journal | vauthors = Burke DG, Chilibeck PD, Parise G, Candow DG, Mahoney D, Tarnopolsky M | title = Effect of creatine and weight training on muscle creatine and performance in vegetarians | journal = Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise | volume = 35 | issue = 11 | pages = 1946–55 | date = November 2003 | pmid = 14600563 | doi = 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093614.17517.79 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Benton D, Donohoe R | title = The influence of creatine supplementation on the cognitive functioning of vegetarians and omnivores | journal = The British Journal of Nutrition | volume = 105 | issue = 7 | pages = 1100–5 | date = April 2011 | pmid = 21118604 | doi = 10.1017/S0007114510004733 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="creatinedefects"/><ref name="pmid26874700"/> This finding is due probably to an omnivorous diet being the primary source of creatine.<ref name="pmid28572496">{{cite journal | vauthors = Solis MY, Artioli GG, Gualano B | title = Effect of age, diet, and tissue type on PCr response to creatine supplementation | journal = [[Journal of Applied Physiology]] | volume = 23 | issue=2 | pages =407-414407–414 | date=2017 | doi =10.1152/japplphysiol.00248.2017 | pmid = 28572496}}</ref> Research shows that supplementation is needed to raise the concentration of creatine in the muscles of [[lacto-ovo vegetarian]]s and [[vegan]]s up to non-vegetarian levels.<ref name="burke"/>

==Pharmacokinetics==

Line 128:

==== Loading phase ====

[[File:Muscle_Total_Creatine_Stores.png|alt=|thumb|485x485px]]

An approximation of 0.3 g/kg/day divided into 4 equal spaced intervals has been suggested since creatine needs may vary based on body weight.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> It has also been shown that taking a lower dose of 3 grams a day for 28 days can also increase total muscle creatine storage to the same amount as the rapid loading dose of 20 g/day for 6 days.<ref name=":2" /> However, a 28-day loading phase does not allow for [[Performance-enhancing substance#Ergogenic aids|ergogenic]] benefits of creatine supplementation to be realized until fully saturated muscle storage.

This elevation in muscle creatine storage has been correlated with ergogenic benefits discussed in the research section. However, higher doses for longer periods of time are being studied to offset creatine synthesis deficiencies and mitigating diseases.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hanna-El-Daher L, Braissant O | title = Creatine synthesis and exchanges between brain cells: What can be learned from human creatine deficiencies and various experimental models? | journal = Amino Acids | volume = 48 | issue = 8 | pages = 1877–95 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 26861125 | doi = 10.1007/s00726-016-2189-0 | s2cid = 3675631 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bender A, Klopstock T | title = Creatine for neuroprotection in neurodegenerative disease: end of story? | journal = Amino Acids | volume = 48 | issue = 8 | pages = 1929–40 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 26748651 | doi = 10.1007/s00726-015-2165-0 | s2cid = 2349130 }}</ref><ref name="creatinedefects" />

Line 151:

Creatine use can increase maximum power and performance in high-intensity anaerobic repetitive work (periods of work and rest) by 5% to 15%.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Bemben MG, Lamont HS |title=Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: recent findings |journal=Sports Medicine |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=107–25 |year=2005 |pmid=15707376 |doi=10.2165/00007256-200535020-00002|s2cid=57734918 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Bird SP |title=Creatine supplementation and exercise performance: a brief review |journal=Journal of Sports Science & Medicine |volume=2 |issue=4 |pages=123–32 |date=December 2003 |pmid=24688272 |pmc=3963244}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F |title=Creatine Supplementation and Lower Limb Strength Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses |journal=Sports Medicine |volume=45 |issue=9 |pages=1285–1294 |date=September 2015 |pmid=25946994 |doi=10.1007/s40279-015-0337-4|s2cid=7372700 }}</ref> Creatine has no significant effect on aerobic [[Endurance#Endurance exercise|endurance]], though it will increase power during short sessions of high-intensity aerobic exercise.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Engelhardt M, Neumann G, Berbalk A, Reuter I |title=Creatine supplementation in endurance sports |journal=Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise |volume=30 |issue=7 |pages=1123–9 |date=July 1998 |pmid=9662683 |doi=10.1097/00005768-199807000-00016|doi-access=free }}</ref>{{Obsolete source|date=May 2018}}<ref name="Graham">{{cite journal |vauthors=Graham AS, Hatton RC |title=Creatine: a review of efficacy and safety |journal=Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association |volume=39 |issue=6 |pages=803–10; quiz 875–7 |year=1999 |pmid=10609446 |doi=10.1016/s1086-5802(15)30371-5}}</ref>{{Obsolete source|date=May 2018}}

Creatine is proven to boost the recovery and work capacity of an athlete, and multi-applicable capabilities upon athletes have given it a lot of interest over the course of the past decade. A survey of 21,000 college athletes showed that 14% of athletes take creatine supplements to try to improve performance.<ref name=":1">{{Cite news|url=https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/ExerciseAndAthleticPerformance-HealthProfessional/#creatine|title=Office of Dietary Supplements - Dietary Supplements for Exercise and Athletic Performance|access-date=2018-05-05|language=en|archive-date=8 May 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180508185512/https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/ExerciseAndAthleticPerformance-HealthProfessional/#creatine|url-status=live}}</ref> Compared to normal athletes, those with creatine supplementation have been shown to produce better athletic performance.<ref>{{Cite journal |title= Creatine for Exercise and Sports Performance, with Recovery Considerations for Healthy Populations|date=2021 |pmc=8228369 |last1=Wax |first1=B. |last2=Kerksick |first2=C. M. |last3=Jagim |first3=A. R. |last4=Mayo |first4=J. J. |last5=Lyons |first5=B. C. |last6=Kreider |first6=R. B. |journal=Nutrients |volume=13 |issue=6 |page=1915 |doi=10.3390/nu13061915 |doi-access=free |pmid=34199588 }}</ref> Non-athletes report taking creatine supplements to improve appearance.<ref name=":1" />

==Research ==

===Cognitive performance===

Creatine is sometimes reported to have a beneficial effect on brain function and cognitive processing, although the evidence is difficult to interpret systematically and the appropriate dosing is unknown.<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal|last1=Dolan|first1=Eimear|last2=Gualano|first2=Bruno|last3=Rawson|first3=Eric S.|date=2019-01-02|title=Beyond muscle: the effects of creatine supplementation on brain creatine, cognitive processing, and traumatic brain injury|url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|journal=European Journal of Sport Science|language=en|volume=19|issue=1|pages=1–14|doi=10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|pmid=30086660|s2cid=51936612|issn=1746-1391|access-date=11 October 2021|archive-date=29 October 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211029174808/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite journal|last1=Rawson|first1=Eric S.|last2=Venezia|first2=Andrew C.|date=May 2011|title=Use of creatine in the elderly and evidence for effects on cognitive function in young and old|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|journal=Amino Acids|language=en|volume=40|issue=5|pages=1349–1362|doi=10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|pmid=21394604|s2cid=11382225|issn=0939-4451|access-date=11 October 2021|archive-date=19 June 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220619121803/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|url-status=live}}</ref> The greatest effect appears to be in individuals who are [[Stress (biology)|stressed]] (due, for instance, to [[sleep deprivation]]) or cognitively impaired.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" /><ref>{{Cite journal|vauthors = Gordji-Nejad|date= 2024 |title= Single dose creatine improves cognitive performance and induces changes in cerebral high energy phosphates during sleep deprivation|journal=Scientific Reports |volume= 14|issue= 1|pages=4937 |doi=10.1038/s41598-024-54249-9 |pmid= 38418482 |pmc=10902318|bibcode= 2024NatSR..14.4937G }}</ref>▼

A 2018 [[systematic review]] found that "generally, there was evidence that short term memory and intelligence/reasoning may be improved by creatine administration", whereas for other cognitive domains "the results were conflicting".<ref>{{cite journal |title=Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials |journal=[[Experimental Gerontology]] |date=2018 |volume=108 |pages=166–173 |pmc=6093191 |last1=Avgerinos |first1=K. I. |last2=Spyrou |first2=N. |last3=Bougioukas |first3=K. I. |last4=Kapogiannis |first4=D. |doi=10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.013 |pmid=29704637 }}</ref> Another 2023 review initially found evidence of improved memory function.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |journal=[[Nutrition Reviews]] |date=2023 |volume=81 |issue=4 |pages=416–27 |doi=10.1093/nutrit/nuac064 |pmid=35984306 |last1=Prokopidis |first1=Konstantinos |last2=Giannos |first2=Panagiotis |last3=Triantafyllidis |first3=Konstantinos K. |last4=Kechagias |first4=Konstantinos S. |last5=Forbes |first5=Scott C. |last6=Candow |first6=Darren G. |pmc=9999677 }}</ref> However, it was later determined that faulty statistics lead to the statistical significance and after fixing the "double counting", the effect was only significant in older adults.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Prokopidis |first1=Konstantinos |last2=Giannos |first2=Panagiotis |last3=Triantafyllidis |first3=Konstantinos K |last4=Kechagias |first4=Konstantinos S |last5=Forbes |first5=Scott C |last6=Candow |first6=Darren G |title=Author's reply: Letter to the Editor: Double counting due to inadequate statistics leads to false-positive findings in "Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials" |journal=Nutrition Reviews |date=16 January 2023 |volume=81 |issue=11 |pages=1497–1500 |doi=10.1093/nutrit/nuac111 |pmid=36644912 |url=https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/nutrit/nuac111/6987897?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false |access-date=31 August 2023}}</ref>▼

▲Creatine is sometimes reported to have a beneficial effect on brain function and cognitive processing, although the evidence is difficult to interpret systematically and the appropriate dosing is unknown.<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal|last1=Dolan|first1=Eimear|last2=Gualano|first2=Bruno|last3=Rawson|first3=Eric S.|date=2019-01-02|title=Beyond muscle: the effects of creatine supplementation on brain creatine, cognitive processing, and traumatic brain injury|url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|journal=European Journal of Sport Science|language=en|volume=19|issue=1|pages=1–14|doi=10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|pmid=30086660|s2cid=51936612|issn=1746-1391|access-date=11 October 2021|archive-date=29 October 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211029174808/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17461391.2018.1500644|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{Cite journal|last1=Rawson|first1=Eric S.|last2=Venezia|first2=Andrew C.|date=May 2011|title=Use of creatine in the elderly and evidence for effects on cognitive function in young and old|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|journal=Amino Acids|language=en|volume=40|issue=5|pages=1349–1362|doi=10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|pmid=21394604|s2cid=11382225|issn=0939-4451|access-date=11 October 2021|archive-date=19 June 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220619121803/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9|url-status=live}}</ref> The greatest effect appears to be in individuals who are [[Stress (biology)|stressed]] (due, for instance, to [[sleep deprivation]]) or cognitively impaired.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9" />

A 2023 systematic review foundstudy no"...supported evidenceclaims that creatine improvedsupplementation cognitivecan performanceincreases [sic] brain creatine content but also demonstrated somewhat equivocal results for effects on cognition. TheIt researchesdoes, criticizedhowever, theprovide methodologyevidence ofto previoussuggest reviewsthat more research is required with stressed populations, as supplementation does appear to significantly affect brain content.<ref>{{Cite journal |lastlast1=McMorris |firstfirst1=Terry |last2=Hale |first2=Beverley J. |last3=Pine |first3=Beatrice S. |last4=Williams |first4=Thomas B. |date=2024-04-04 |title=Creatine supplementation research fails to support the theoretical basis for an effect on cognition: Evidence from a systematic review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38582412/ |journal=Behavioural Brain Research |volume=466 |pages=114982 |doi=10.1016/j.bbr.2024.114982 |issn=1872-7549 |pmid=38582412|doi-access=free }}</ref>▼

▲A 2018 [[systematic review]] found that "generally, there was evidence that short term memory and intelligence/reasoning may be improved by creatine administration", whereas for other cognitive domains "the results were conflicting".<ref>{{cite journal |title=Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials |journal=[[Experimental Gerontology]] |date=2018 |volume=108 |pages=166–173 |pmc=6093191 |last1=Avgerinos |first1=K. I. |last2=Spyrou |first2=N. |last3=Bougioukas |first3=K. I. |last4=Kapogiannis |first4=D. |doi=10.1016/j.exger.2018.04.013 |pmid=29704637 }}</ref> Another 2023 review initially found evidence of improved memory function.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |journal=[[Nutrition Reviews]] |date=2023 |volume=81 |issue=4 |pages=416–27 |doi=10.1093/nutrit/nuac064 |pmid=35984306 |last1=Prokopidis |first1=Konstantinos |last2=Giannos |first2=Panagiotis |last3=Triantafyllidis |first3=Konstantinos K. |last4=Kechagias |first4=Konstantinos S. |last5=Forbes |first5=Scott C. |last6=Candow |first6=Darren G. |pmc=9999677 }}</ref> However, it was later determined that faulty statistics lead to the statistical significance and after fixing the "double counting", the effect was only significant in older adults.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Prokopidis |first1=Konstantinos |last2=Giannos |first2=Panagiotis |last3=Triantafyllidis |first3=Konstantinos K |last4=Kechagias |first4=Konstantinos S |last5=Forbes |first5=Scott C |last6=Candow |first6=Darren G |title=Author's reply: Letter to the Editor: Double counting due to inadequate statistics leads to false-positive findings in "Effects of creatine supplementation on memory in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials" |journal=Nutrition Reviews |date=16 January 2023 |volume=81 |issue=11 |pages=1497–1500 |doi=10.1093/nutrit/nuac111 |url=https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/nutrit/nuac111/6987897?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false |access-date=31 August 2023}}</ref>

▲A 2023 systematic review found no evidence that creatine improved cognitive performance. The researches criticized the methodology of previous reviews.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McMorris |first=Terry |last2=Hale |first2=Beverley J. |last3=Pine |first3=Beatrice S. |last4=Williams |first4=Thomas B. |date=2024-04-04 |title=Creatine supplementation research fails to support the theoretical basis for an effect on cognition: Evidence from a systematic review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38582412/ |journal=Behavioural Brain Research |volume=466 |pages=114982 |doi=10.1016/j.bbr.2024.114982 |issn=1872-7549 |pmid=38582412}}</ref>

===Muscular disease===

Line 193 ⟶ 192:

A 2009 systematic review discredited concerns that creatine supplementation could affect hydration status and heat tolerance and lead to muscle cramping and diarrhea.<ref name="Lopez RM, Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Ganio MS, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM 2009 215–23">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lopez RM, Casa DJ, McDermott BP, Ganio MS, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM | title = Does creatine supplementation hinder exercise heat tolerance or hydration status? A systematic review with meta-analyses | journal = Journal of Athletic Training | volume = 44 | issue = 2 | pages = 215–23 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19295968 | pmc = 2657025 | doi = 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.215 }}</ref><ref name="Dalbo VJ, Roberts MD, Stout JR, Kerksick CM 2008 567–73">{{cite journal | vauthors = Dalbo VJ, Roberts MD, Stout JR, Kerksick CM | title = Putting to rest the myth of creatine supplementation leading to muscle cramps and dehydration | journal = British Journal of Sports Medicine | volume = 42 | issue = 7 | pages = 567–73 | date = July 2008 | pmid = 18184753 | doi = 10.1136/bjsm.2007.042473 | s2cid = 12920206 | url = http://hdl.cqu.edu.au/10018/55591 | access-date = 27 December 2021 | archive-date = 19 June 2022 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220619121814/https://acquire.cqu.edu.au/articles/journal_contribution/Putting_to_rest_the_myth_of_creatine_supplementation_leading_to_muscle_cramps_and_dehydration/13449578 | url-status = live }}</ref>

Despite weight gain due to water retention and potential cramps being two seemingly "common" side effects, new research indicates that these side effects are likely not the result of creatine usage. In addition, the initial water retention is attributed to more short-term creatine use (the "loading" phase). Studies have shown that creatine usage does not necessarily affect total body water relative to muscle mass in the long-term.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1=Antonio | first1=Jose | date=2022 | title=Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show? | journal=Journal of the International Society of Sports Medicine | volume=18 | doi=10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w | doi-access=free | pmc=7871530 }}</ref>

=== Renal function ===

Line 227 ⟶ 228:

== External links ==

{{commons category}}

* [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe-srv/PDBeXplore/ligand/?ligand=CRN Creatine bound to proteins] in the [[Protein Data Bank|PDB]]

{{subject bar|auto=y|d=y}}

{{dietary supplement}}

{{Authority control}}