Diet and obesity

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

Diet plays an important role in the genesis of obesity. Personal choices, advertising, social customs and cultural influences, as well as food availability and pricing all play a role in determining what and how much an individual eats.

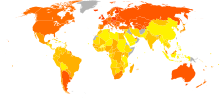

no data <1600 1600-1800 1800-2000 2000-2200 2200-2400 2400-2600 2600-2800 2800-3000 3000-3200 3200-3400 3400-3600 >3600 |

no data <1600 1600-1800 1800-2000 2000-2200 2200-2400 2400-2600 2600-2800 2800-3000 3000-3200 3200-3400 3400-3600 >3600 |

no data <1600 1600–1800 1800–2000 2000–2200 2200–2400 2400–2600 2600–2800 2800–3000 3000–3200 3200–3400 3400–3600 >3600 |

Dietary energy supply

The dietary energy supply is the food available for human consumption, usually expressed in kilocalories per person per day. It gives an overestimate of the total amount of food consumed as it reflects both food consumed and food wasted.[2] The per capita dietary energy supply varies markedly between different regions and countries. It has also changed significantly over time.[3] From the early 1970s to the late 1990s, the average calories available per person per day (the amount of food bought) has increased in all part of the world except Eastern Europe and parts of Africa. The United States had the highest availability with 3654 calories per person in 1996.[4] This increased further in 2002 to 3770.[5] During the late 1990s, Europeans had 3394 calories per person, in the developing areas of Asia there were 2648 calories per person, and in sub-Sahara Africa people had 2176 calories per person.[4][6]

Average calorie consumption

From 1971 – 2000, the average daily number of calories which women consumed in the United States increased by 335 calories per day (1542 calories in 1971 and 1877 calories in 2000). For men, the average increase was 168 calories per day (2450 calories in 1971 and 2618 calories in 2000). Most of these extra calories came from an increase in carbohydrate consumption rather than an increase in fat consumption.[8] The primary sources of these extra carbohydrates were sweetened beverages, which now accounts for almost 25 percent of daily calories in young adults in America.[9] As these estimates are based on a person's recall, they may underestimate the amount of calories actually consumed.[8]

Fast food

As societies become increasingly reliant on energy-dense fast-food meals, the association between fast food consumption and obesity becomes more concerning.[10] In the United States consumption of fast food meal has tripled and calorie intake from fast food has quadrupled between 1977 and 1995.[11] Consumption of sweetened drinks is also believed to be a major contributor to the rising rates of obesity.[12][13]

Portion size

The portion size of many prepackage and restaurant foods have increased in both the United States and Denmark since the 1970s.[8] Fast food serving for example 2 to 5 times larger than they were in the 1980s. Evidence has shown that larger portions of energy-dense foods lead to greater energy intake and thus to greater rates of obesity.[14][15]

Sugar consumption

Existing evidence from large-scale cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies supports that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is correlated with the childhood and adult obesity epidemic in the United States population (Malik et al. 2006). Sweetened drinks containing either sucrose alone or sucrose in combination with fructose appear to lead to weight gain due to increase energy intake.[16] In fact, about half of total added sugar consumed in the United States is in liquid form. [17] Teenage boys showed the greatest consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, upwards of 357 calories per day. [17] In addition to the evidence that humans have a natural propensity towards sugar [18], there exists additional biological plausibility that explains the correlation of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and obesity. [19]

Sugar-sweetened beverages raise concern because they are calorie-dense and yet produce low satiety. [20] There exists a strong correlation between the consumption of liquid calories and total energy intake. Individuals do not tend to decrease solid calories in compensation for increased liquid calories. [19] For example, if there were no compensation for liquid calories, the 40-50g of sugar in each 12 oz. can of soda drunk on a daily basis could lead to a 15 pound weight gain.[19] On the national scale, the American Heart Association estimates that approximately half of the total caloric intake increase over the past 30 years is attributable to liquid calories. [21] The high glycemic load of these beverages is also thought to be a contributor to chronic disease, including diabetes [20] and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. [22] Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that suggests sugar may be an addictive substance, further potentiating any individuals’ existing problem of excessive consumption. [18]

Based on socioecological models of health, it is easy to understand how sugar-sweetened beverages have sustained numerous historical changes that have made them widely appealing and available. For example, the soda industry budget for advertising in 2000 totaled over $700 million, an increase of over $381 million since 1986. [17] Furthermore, standard serving sizes have doubled from 8-ounce to 12-ounce bottles between 1977-1996. [17] Price incentives from beverage companies have maintained their products very cheap [23] This obesogenic environment has promoted the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages on a national level correlating with trends in the obesity epidemic.

Social policy and change

Agricultural policy and techniques in the United States and Europe have led to lower food prices. In the United States, subsidization of corn, soy, wheat, and rice through the U.S. farm bill has made the main sources of processed food cheap compared to fruits and vegetables.[24]

Evidence does not support the commonly expressed view that some obese people eat little yet gain weight due to a slow metabolism. On average obese people have a greater energy expenditure than normal weight or thin people.[25] This is because it takes more energy to maintain an increased body mass.[26] Obese people also underreport how much food they consume compared to those of normal weight.[27] Tests of human subjects carried out in a calorimeter support this conclusion.[28]

See Also

References

- ^ a b "Compendium of food and agriculture indicators - 2006". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "Compendium of food and agriculture indicators - 2006". FAO. Retrieved February 18, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Compendium of food and agriculture indicators - 2006". UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b "Calories per capita per day" (gif). UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved January 10, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "www.fao.org" (PDF). UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ "USDA: frsept99b". USDA. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ "In the Long Run" (pdf). USDA. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c Wright JD, Kennedy-Stephenson J, Wang CY, McDowell MA, Johnson CL (2004). "Trends in intake of energy and macronutrients—United States, 1971–2000". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 53 (4): 80–2. PMID 14762332. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Caballero B (2007). "The global epidemic of obesity: An overview". Epidemiol Rev. 29: 1–5. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxm012. PMID 17569676.

- ^ Rosenheck R (2008). "Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk". Obes Rev. 9 (6): 535–47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x. PMID 18346099.

- ^ Lin BH, Guthrie J and Frazao E (1999). "Nutrient contribution of food away from home". In Frazão E (ed.). Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 750: America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. pp. 213–239.

- ^ Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB (2006). "Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 84 (2): 274–88. PMC 3210834. PMID 16895873. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL (2009). "Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity". Obes Rev. 10 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00523.x. PMID 18764885.

- ^ Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ (2005). "Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic". J. Nutr. 135 (4): 905–9. PMID 15795457. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Steenhuis IH, Vermeer WM (2009). "Portion size: review and framework for interventions". Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 6: 58. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-6-58. PMC 2739837. PMID 19698102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Tappy, L (2010 Jan). "Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity". Physiological reviews. 90 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1152/physrev.00019.2009. PMID 20086073. ;

- ^ a b c d Woodward-Lopez G, Kao J, Ritchie L. (2010) To what extent have sweetened beverages contributed to the obesity epidemic? Public Health Nutrition.14(3), 499-509.

- ^ a b Avena, N.M., Rada, P., Hoebel, B.G. Evidence for sugar addiction: Behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neuroscience Biobehavioral Review. (2008) 32(1): 20-39.

- ^ a b c Malik, V.S., Schulze, M.B., & Hu, F.B. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. (2006) 84: 274-288.

- ^ a b Hu, F., Malik, V. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type II diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiology and Behavior. (2010) 100: 47-54.

- ^ Johnson, R.K., Appel, L.J., Brands, M., Howard, B.V., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R.H., Sacks, F., Steffen, L.M., Wylie-Rosett, J. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. (2009) 120: 1011-1020.

- ^ Assy, N. Nasser, G. Kamayse, I., Nseir, W., Beniashvili, Z., Djibre, A., Grosovski, M. Soft drink consumption linked with fatty liver in the absence of traditional risk factors. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. (2008). 22(10): 811-816.

- ^ Brownell, K.D., Farley, T., Willett, W.C., Popkin, B.M., Chaloupka, F.J., Thompson, J.W., Ludwig, D.S. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. The New England Journal of Medicine. (2009) 361(16):1599-1605.

- ^ Pollan, Michael (22 April 2007). "You Are What You Grow". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ Kushner, Robert (2007). Treatment of the Obese Patient (Contemporary Endocrinology). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 158. ISBN 1-59745-400-1. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ Adams JP, Murphy PG (2000). "Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care". Br J Anaesth. 85 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1093/bja/85.1.91. PMID 10927998.

- ^ Peter G. Kopelman, Ian D. Caterson, Michael J. Stock, William H. Dietz (2005). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 140-511672-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "mdPassport". Retrieved December 31, 2008.