Hadith: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Line 4:

{{Use American English|date=May 2024}}

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}}

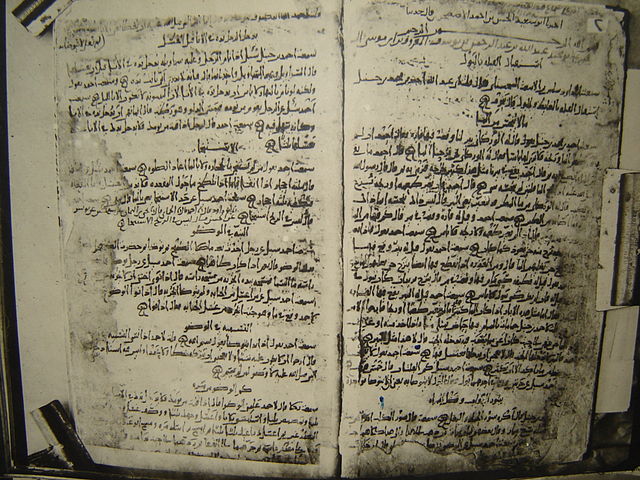

[[ImageFile:Ibnhanbal.jpg|thumb|250x250px|A manuscript of [[Ahmad ibn Hanbal|Ibn Hanbal's]] Islamic legal writings ([[Sharia]]), produced October 879|250x250px]]▼

'''Hadith{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|æ|d|ɪ|θ}}<ref name=":1">{{OED|hadith}}</ref> or {{IPAc-en|h|ɑː|ˈ|d|iː|θ}};<ref>{{dictionary.com|Hadith|access-date=2011-08-13}}</ref> {{lang-ar|حديث|translit=ḥadīth}}, {{IPA-|ar|ħadiːθ}}; {{abbr|pl.|plural}} '''{{transliteration|ar|aḥādīth}}''', {{lang|ar|أحاديث}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''ʾaḥādīṯ''}},{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}}{{efn|The plural form of hadith in Arabic is {{transliteration|ar|aḥādīth}}, {{lang|ar|أحاديث}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''{{'}}aḥādīth''}} but ''hadith'' will be used instead in this article.}} {{IPA-|ar|ʔaħaːdiːθ}}, {{lit|talk|discourse}}}}''' ({{lang-ar|حديث|translit=ḥadīth}}) or '''Atharathar''' ({{lang-ar|أثر}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''ʾAṯar''}}, {{lit|remnant|effect}})<ref name="SiH">{{cite book |last=Azami |first=Muhammad Mustafa |author-link=Muhammad Mustafa Azmi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qblMCwAAQBAJ&q=hadith+athar&pg=PA3 |title=Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature |publisher=American Trust Publications |year=1978 |isbn=978-0-89259-011-7 |page=3 |access-date=16 December 2022}}</ref> is a form of Islamic [[oral tradition]] containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the prophet [[Muhammad]]. Each hadith is associated with a chain of narrators (a lineage of people who reportedly heard and repeated the hadith, from which the source of the hadith can apparently be traced). Compilations of hadith were collected by Islamic scholars (known as [[Muhaddith|Muhaddiths]]) in the centuries after Muhammad's death. Hadith are widely respected in mainstream Muslim thought and are central to [[Islamic Law|Islamic law]].▼

{{Hadith}}

{{transliteration|ar|Ḥadīth}} is the Arabic word for things like a report or an account (of an event).{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/HansWehrEnglishArabicDctionarySearchableFormat|title=Hans Wehr English&Arabic Dictionary}}</ref><ref name="Modarresi">{{cite book|author=Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi|author-link=Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi|title=The Laws of Islam|date=26 March 2016|publisher=Enlight Press|isbn=978-0994240989|url=http://almodarresi.com/en/books/pdf/TheLawsofIslam.pdf|access-date=22 December 2017|ref=Modarresi|language=en|archive-date=2 August 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190802163247/http://almodarresi.com/en/books/pdf/TheLawsofIslam.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{rp|471}} For many, the authority of hadith is a source for religious and moral guidance known as [[Sunnah]], which ranks second only to that of the [[Quran]]<ref name="EB">{{cite web |title=Hadith |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hadith |website=Encyclopaedia Britannica |access-date=31 July 2020}}</ref> (which Muslims hold to be the word of [[God in Islam|God]] revealed to Muhammad). While the number of verses pertaining to law in the Quran is relatively small, hadith are considered by many to give direction on everything from details of religious obligations (such as {{transliteration|ar|[[Ghusl]]}} or {{transliteration|ar|[[Wudu]]}}, ablutions<ref name="GotRMZK1975:203">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.203</ref> for {{transliteration|ar|[[salat]]}} prayer), to the correct forms of salutations<ref name="GotRMZK1975:168">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.168</ref> and the importance of benevolence to slaves.<ref name="GotRMZK1975:229">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.229</ref> Thus for many, the "great bulk" of the rules of [[Sharia]] are derived from hadith, rather than the Quran.<ref name="Forte-1978-2">{{cite journal|last1=Forte|first1=David F.|title=Islamic Law; the impact of Joseph Schacht|journal=Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review |date=1978|volume=1|page=2 |url=http://www.soerenkern.com/pdfs/islam/IslamicLawTheImpactofJosephSchacht.pdf |access-date=19 April 2018}}</ref>{{#tag:ref|"The full systems of Islamic theology and law are not derived primarily from the Quran. Muhammad's sunna was a second but far more detailed living scripture, and later Muslim scholars would thus often refer to Muhammad as 'The Possessor of Two Revelations'".<ref name="JACBMM2014:18">[[#JACBMM2014|J.A.C. Brown, ''Misquoting Muhammad'', 2014]]: p.18</ref>|group=Note}} Among scholars of [[Sunni Islam]] the term hadith may include not only the words, advice, practices, etc. of Muhammad, but also those of his [[Sahabah|companions]].<ref name="EIMW-2004-285">{{cite book |last1=Motzki |first1=Harald |title=Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World.1 |date=2004 |publisher=Thmpson Gale |page=285}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Al-Bukhari |first=Imam |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q9E4egv4lKEC |title=Moral Teachings of Islam: Prophetic Traditions from Al-Adab Al-mufrad By Muḥammad ibn Ismāʻīl Bukhārī |publisher=Rowman Altamira |year=2003 |isbn=9780759104174}}</ref> In [[Shia Islam]], hadith are the embodiment of the sunnah, the words and actions of Muhammad and his family, the {{transliteration|ar|[[Ahl al-Bayt]]}} ([[The Twelve Imams]] and Muhammad's daughter, [[Fatimah]]).<ref name="Intro-hadith-vii">{{cite book |last1=al-Fadli |first1=Abd al-Hadi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E-muq9pi0zUC&q=shia+hadith |title=Introduction to Hadith |date=2011 |publisher=ICAS Press |isbn=9781904063476 |edition=2nd |location=London |page=vii }}{{Dead link|date=April 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> ▼

{{Muhammad}}

▲'''Hadith{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|æ|d|ɪ|θ}}<ref name=":1">{{OED|hadith}}</ref> or {{IPAc-en|h|ɑː|ˈ|d|iː|θ}};<ref>{{dictionary.com|Hadith|access-date=2011-08-13}}</ref> {{lang-ar|حديث|translit=ḥadīth}}, {{IPA-ar|ħadiːθ}}; {{abbr|pl.|plural}} '''{{transliteration|ar|aḥādīth}}''', {{lang|ar|أحاديث}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''ʾaḥādīṯ''}},{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}}{{efn|The plural form of hadith in Arabic is {{transliteration|ar|aḥādīth}}, {{lang|ar|أحاديث}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''{{'}}aḥādīth''}} but ''hadith'' will be used instead in this article.}} {{IPA-ar|ʔaħaːdiːθ}}, {{lit|talk|discourse}}}}''' ({{lang-ar|حديث|translit=ḥadīth}}) or '''Athar''' ({{lang-ar|أثر}}, {{transliteration|ar|DIN|''ʾAṯar''}}, {{lit|remnant|effect}})<ref name="SiH">{{cite book |last=Azami |first=Muhammad Mustafa |author-link=Muhammad Mustafa Azmi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qblMCwAAQBAJ&q=hadith+athar&pg=PA3 |title=Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature |publisher=American Trust Publications |year=1978 |isbn=978-0-89259-011-7 |page=3 |access-date=16 December 2022}}</ref> is a form of Islamic [[oral tradition]] containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the prophet [[Muhammad]]. Each hadith is associated with a chain of narrators (a lineage of people who reportedly heard and repeated the hadith, from which the source of the hadith can apparently be traced). Compilations of hadith were collected by Islamic scholars in the centuries after Muhammad's death. Hadith are widely respected in mainstream Muslim thought and are central to [[Islamic Law|Islamic law]].

▲{{transliteration|ar|Ḥadīth}} is the Arabic word for things like a report or an account (of an event).{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/HansWehrEnglishArabicDctionarySearchableFormat|title=Hans Wehr English&Arabic Dictionary}}</ref><ref name="Modarresi">{{cite book|author=Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi|author-link=Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi|title=The Laws of Islam|date=26 March 2016|publisher=Enlight Press|isbn=978-0994240989|url=http://almodarresi.com/en/books/pdf/TheLawsofIslam.pdf|access-date=22 December 2017|ref=Modarresi|language=en|archive-date=2 August 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190802163247/http://almodarresi.com/en/books/pdf/TheLawsofIslam.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{rp|471}} For many, the authority of hadith is a source for religious and moral guidance known as [[Sunnah]], which ranks second only to that of the [[Quran]]<ref name="EB">{{cite web |title=Hadith |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hadith |website=Encyclopaedia Britannica |access-date=31 July 2020}}</ref> (which Muslims hold to be the word of [[God in Islam|God]] revealed to Muhammad). While the number of verses pertaining to law in the Quran is relatively small, hadith are considered by many to give direction on everything from details of religious obligations (such as {{transliteration|ar|[[Ghusl]]}} or {{transliteration|ar|[[Wudu]]}}, ablutions<ref name="GotRMZK1975:203">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.203</ref> for {{transliteration|ar|[[salat]]}} prayer), to the correct forms of salutations<ref name="GotRMZK1975:168">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.168</ref> and the importance of benevolence to slaves.<ref name="GotRMZK1975:229">[[#GotRMZK1975|An-Nawawi, ''Riyadh As-Salihin'', 1975]]: p.229</ref> Thus for many, the "great bulk" of the rules of [[Sharia]] are derived from hadith, rather than the Quran.<ref name="Forte-1978-2">{{cite journal|last1=Forte|first1=David F.|title=Islamic Law; the impact of Joseph Schacht|journal=Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review |date=1978|volume=1|page=2 |url=http://www.soerenkern.com/pdfs/islam/IslamicLawTheImpactofJosephSchacht.pdf |access-date=19 April 2018}}</ref>{{#tag:ref|"The full systems of Islamic theology and law are not derived primarily from the Quran. Muhammad's sunna was a second but far more detailed living scripture, and later Muslim scholars would thus often refer to Muhammad as 'The Possessor of Two Revelations'".<ref name="JACBMM2014:18">[[#JACBMM2014|J.A.C. Brown, ''Misquoting Muhammad'', 2014]]: p.18</ref>|group=Note}} Among scholars of [[Sunni Islam]] the term hadith may include not only the words, advice, practices, etc. of Muhammad, but also those of his [[Sahabah|companions]].<ref name="EIMW-2004-285">{{cite book |last1=Motzki |first1=Harald |title=Encyclopedia of Islam and Muslim World.1 |date=2004 |publisher=Thmpson Gale |page=285}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Al-Bukhari |first=Imam |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q9E4egv4lKEC |title=Moral Teachings of Islam: Prophetic Traditions from Al-Adab Al-mufrad By Muḥammad ibn Ismāʻīl Bukhārī |publisher=Rowman Altamira |year=2003 |isbn=9780759104174}}</ref> In [[Shia Islam]], hadith are the embodiment of the sunnah, the words and actions of Muhammad and his family, the {{transliteration|ar|[[Ahl al-Bayt]]}} ([[The Twelve Imams]] and Muhammad's daughter, [[Fatimah]]).<ref name="Intro-hadith-vii">{{cite book |last1=al-Fadli |first1=Abd al-Hadi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E-muq9pi0zUC&q=shia+hadith |title=Introduction to Hadith |date=2011 |publisher=ICAS Press |isbn=9781904063476 |edition=2nd |location=London |page=vii }}{{Dead link|date=April 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref>

▲[[Image:Ibnhanbal.jpg|thumb|A manuscript of [[Ahmad ibn Hanbal|Ibn Hanbal's]] Islamic legal writings (Sharia), produced October 879|250x250px]]

Unlike the Quran, not all Muslims believe that hadith accounts (or at least not all hadith accounts) are divine revelation. Different collections of hadīth would come to differentiate the different branches of the Islamic faith.<ref name=JACBMM2014:8>[[#JACBMM2014|J.A.C. Brown, ''Misquoting Muhammad'', 2014]]: p.8</ref> Some Muslims believe that Islamic guidance should be based on the [[Quranism|Quran only]], thus rejecting the authority of hadith; some further claim that most hadiths are fabrications ([[pseudepigrapha]]) created in the 8th and 9th centuries AD, and which are falsely attributed to Muhammad.<ref name="Aisha Y. Musa 2013">Aisha Y. Musa, The Qur’anists, Florida International University, accessed May 22, 2013.</ref><ref name="Neal Robinson 2013 pp. 85-89">Neal Robinson (2013), Islam: A Concise Introduction, Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0878402243}}, Chapter 7, pp. 85-89</ref> Historically, some sects of the [[Kharijites]] also rejected the hadiths, while [[Mu'tazilites]] rejected the hadiths as the basis for Islamic law, while at the same time accepting the Sunnah and [[Ijma]].<ref name="Rowman & Littlefield">{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j8c_DwAAQBAJ&dq=khawarij+rejected+the+hadith&pg=PA75 | title=Major Issues in Islam: The Challenges within and Without | isbn=978-0-7618-7017-3 | last1=Sindima | first1=Harvey J. | date=2 November 2017 | publisher=Rowman & Littlefield }}</ref><ref name="Lulu.com">{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=G-M3IRh22moC&dq=some+mutazilites+rejected+hadiths&pg=PA63 | title=Science Under Islam: Rise, Decline and Revival | isbn=9781847999429 | last1=Deen | first1=Sayyed M. | year=2007 | publisher=Lulu.com }}</ref>

Because some hadith contain questionable and even contradictory statements, the authentication of hadith became a major [[Hadith studies|field of study]] in Islam.<ref name="IatW-Lewis-44">{{cite book|last1=Lewis|first1=Bernard|title=Islam and the West|date=1993|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=[https://archive.org/details/islamwest00lewi_0/page/44 44]|url=https://archive.org/details/islamwest00lewi_0|url-access=registration|quote=hadith.|access-date=28 March 2018|isbn=9780198023937}}</ref> In its classic form a hadith consists of two parts—the chain of narrators who have transmitted the report (the {{transliteration|ar|isnad}}), and the main text of the report (the {{transliteration|ar|matn}}).<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=|title=Surah Al-Jumu'a, Word by word translation of verse number 2-3 (Tafsir included) {{!}} الجمعة - Quran O|url=https://qurano.com/en/62-al-jumu-a/|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=2021-01-31|website=qurano.com|language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=4}}{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=6-7}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Islahi |first= Amin Ahsan |title= Mabadi Tadabbur-i-Hadith (translated as: "Fundamentals of Hadith Interpretation") |year=1989 |orig-year=transl. 2009 |publisher=Al-Mawrid |location= Lahore |url= http://www.monthly-renaissance.com/DownloadContainer.aspx?id=71 |author-link= Amin Ahsan Islahi |access-date=2 June 2011 |language=ur}}</ref><ref name="H-EoI"/> Individual hadith are classified by Muslim clerics and jurists into categories such as {{transliteration|ar|sahih}} ("authentic"), {{transliteration|ar|hasan}} ("good"), or {{transliteration|ar|da'if}} ("weak").<ref>The Future of Muslim Civilisation by Ziauddin Sardar, 1979, page 26.</ref> However, different groups and different scholars may classify a hadith differently. Historically, some hadiths deemed to be unreliable were still used by Sunni jurists for non-core areas of law.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Brown |first=Jonathan |date=2011 |title=Even If It's Not True It's True: Using Unreliable Hadīths in Sunni Islam |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156851910x517056 |journal=Islamic Law and Society |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=1–52 |doi=10.1163/156851910x517056 |issn=0928-9380}}</ref>

Western scholars are generally skeptical of the value of hadith for understanding the true historical Muhammad, even those considered {{transliteration|ar|sahih}} by Muslim scholars, due to their first recording centuries after Muhammad's life and, the unverifiability of the claimed chains of transmission, and the widespread creation of fraudulent hadiths. Western scholars instead see hadith as more valuable for recording later developments in Islamic theology.<ref name=":0">{{Citation |last=Brown |first=Daniel W. |title=Western Hadith Studies |date=2020-01-02 |work=The Wiley Blackwell Concise Companion to the Hadith |pages=39–56 |editor-last=Brown |editor-first=Daniel W. |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118638477.ch2 |access-date=2024-06-26 |edition=1 |publisher=Wiley |language=en |doi=10.1002/9781118638477.ch2 |isbn=978-1-118-63851-4}}</ref>

==Etymology==

In Arabic, the noun {{transliteration|ar|ALA|ḥadīth}} ({{lang|ar|حديث}} {{IPA-|ar|ħæˈdiːθ|IPA}}) means "report", "account", or "narrative".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ejtaal.net/aa/#hw4=203,ll=567,ls=0,la=796,sg=286,ha=128,br=219,pr=40,aan=125,mgf=199,vi=111,kz=400,mr=146,mn=240,uqw=319,umr=239,ums=186,umj=151,ulq=533,uqa=90,uqq=64|title=Mawrid Reader|work=ejtaal.net}}</ref><ref>''al-Kuliyat'' by Abu al-Baqa’ al-Kafawi, p. 370; Mu'assasah l-Risalah. This last phrase is quoted by al-Qasimi in ''Qawaid al-Tahdith'', p. 61; Dar al-Nafais.</ref> Its Arabic plural is {{transliteration|ar|ALA|aḥādīth}} ({{lang|ar|أحاديث}} {{IPA-|ar|ʔæħæːˈdiːθ|}}).{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}} ''Hadith'' also refers to the speech of a person.<ref>''Lisan al-Arab'', by Ibn Manthour, vol. 2, p. 350; Dar al-Hadith edition.</ref>

==Definition==

Line 50 ⟶ 47:

==Hadith compilation==

The hadith literature in use today is based on spoken reports in circulation after the death of Muhammad. Unlike the Quran, hadithHadith were not promptly written down during Muhammad's lifetime or immediately after his death.{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=3}} Hadith were [[Hadith studies|evaluated]] orally to written and gathered into large collections during the 8th and 9th centuries, generations after Muhammad's death, after the end of the era of the [[Rashidun Caliphate]], over 1,000 km (600 mi) from where Muhammad lived.

"Many thousands of times" more numerous than the verses of the Quran,<ref name=JACBMM2014:94>[[#JACBMM2014|J.A.C. Brown, ''Misquoting Muhammad'', 2014]]: p.94</ref> hadith have been described as resembling layers surrounding the "core" of Islamic beliefs (the Quran). Well-known, widely accepted hadith make up the narrow inner layer, with a hadith becoming less reliable and accepted with each layer stretching outward.<ref name=JACBMM2014:8/>

Line 65 ⟶ 62:

According to Schacht, (and other scholars)<ref>Ignaz Goldziher, ''The Zahiris: Their Doctrine and their History'', trans and ed. Wolfgang Behn (Leiden, 1971), 20 ff</ref><ref name="DWBRTMIT1996:7">[[#DWBRTMIT1996|Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996]]: p.7</ref> in the very first generations after the death of Muhammad, use of hadith from {{transliteration|ar|[[Sahabah]]}} ("companions" of Muhammad) and {{transliteration|ar|[[Tabi'un]]}} ("successors" of the companions) "was the rule", while use of hadith of Muhammad himself by Muslims was "the exception".<ref name="Schacht-OoMJ-1959-3" /> Schacht credits [[Al-Shafi'i]]—founder of the [[Shafi'i]] school of {{transliteration|ar|[[fiqh]]}} (or {{transliteration|ar|[[madh'hab]]}})—with establishing the principle of the using the hadith of Muhammad for Islamic law, and emphasizing the inferiority of hadith of anyone else, saying hadiths:

<blockquote>"... from other persons are of no account in the face of a tradition from the Prophet, whether they confirm or contradict it; if the other persons had been aware of the tradition from the Prophet, they would have followed it".<ref name=Schacht-OoMJ-1959>{{cite book |title=The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence |last1=Schacht |first1=Joseph |publisher=Oxford University Press |orig-year= 1950 |year= 1959 |page=12 }}</ref><ref name=tr-III-intro>{{cite book |last1=Shafi'i |chapter=Introduction. Kitab Ikhtilaf Malid wal-Shafi'i | title=Kitab al-Umm vol. vii}}</ref></blockquote>

This led to "the almost complete neglect" of traditions from the Companions and others.<ref name=Schacht-OoMJ-1959-4>{{cite book |title=The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence |last1=Schacht |first1=Joseph |publisher=Oxford University Press |orig-year= 1950 |year= 1959 |page=4 }}</ref>

Line 91 ⟶ 88:

===Types===

{{anchor|Sacred hadith}} Hadith may be ''[[Hadith Qudse|hadith qudsi]]'' (sacred hadith) — which—which some Muslims regard as the words of [[God in Islam|God]]<ref>Graham, William A. (1977). ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=Fl6skqM6aP8C Divine Word and Prophetic Word in Early Islam: A Reconsideration of the Sources, with Special Reference to the Divine Saying or Hadith Qudsi]''. [[Walter de Gruyter]]. {{ISBN|3110803593}}.</ref> — or—or ''hadith sharif'' (noble hadith), which are Muhammad's own utterances.<ref name="Glasse-159">{{cite book|last1=Glasse|first1=Cyril|title=The New Encyclopedia of Islam|orig-year=1989 |date=2001|publisher=Altamira|page=159}}</ref>

According to as-Sayyid ash-Sharif al-Jurjani, the hadith qudsi differ from the Quran in that the former are "expressed in Muhammad's words", whereas the latter are the "[[Revelation|direct words of God]]". A ''hadith qudsi'' need not be a ''sahih'' (sound hadith), but may be ''da'if'' or even ''mawdu'''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aslamna.info/hadith_qudsi.html|title=Qu'est-ce que le hadith Qudsi ?|work=aslamna.info}}</ref>

Line 102 ⟶ 99:

===Components===

The two major aspects of a hadith are the text of the report (the ''matn''), which contains the actual narrative, and the chain of narrators (the ''isnad''), which documents the route by which the report has been transmitted.{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=4}}<ref name="H-EoI"/> The isnad was an effort to document that a hadith actually came from Muhammad, and Muslim scholars from the eighth century to the present have never ceased to repeat the mantra "The isnad is part of the religion — ifreligion—if not for the isnad, whoever wanted could say whatever they wanted."{{sfn|Brown|2009|p=4}} The ''isnad'' literally means "support", and it is so named because hadith specialists rely on it to determine the [[hadith terminology|authenticity or weakness of a hadith]].<ref>''Tadrib al-Rawi'', vol. 1, pp. 39–41 with abridgement.</ref> The ''isnad'' consists of a chronological list of the narrators, each mentioning the one from whom they heard the hadith, until mentioning the originator of the ''matn'' along with the ''matn'' itself.

The first people to hear hadith were the companions who preserved it and then conveyed it to those after them. Then the generation following them received it, thus conveying it to those after them and so on. So a companion would say, "I heard the Prophet say such and such." The Follower would then say, "I heard a companion say, 'I heard the Prophet.{{' "}} The one after him would then say, "I heard someone say, 'I heard a Companion say, 'I heard the Prophet ...<nowiki>''</nowiki>" and so on.<ref>''Ilm al-Rijal wa Ahimiyatih'', by Mualami, p. 16, Dar al-Rayah.</ref>

==Hadith literature by branch or denomination of Islam==

Line 150 ⟶ 147:

In 851 the rationalist [[Mu`tazila]] school of thought fell out of favor in the [[Abbasid Caliphate]].{{citation needed|date=January 2016}} The Mu`tazila, for whom the "judge of truth ... was human reason,"<ref name=Martin>{{cite book|last1=Martin|first1=Matthew|title=Mu'tazila - use of reason in Islamic theology|date=2013|publisher=Amazon|url=http://www.mutazila.net/|access-date=8 September 2015}}</ref> had clashed with traditionists who looked to the literal meaning of the Quran and hadith for truth. While the Quran had been officially compiled and approved, hadiths had not.

One result was the number of hadiths began "multiplying in suspiciously direct correlation to their utility" to the quoter of the hadith ([[Hadith studies#Muhaddith as school of thought|Traditionists]]{{Broken anchor|date=2024-07-23|bot=User:Cewbot/log/20201008/configuration|target_link=Hadith studies#Muhaddith as school of thought|reason= }} quoted hadith warning against listening to human opinion instead of Sharia; [[Hanafite]]s quoted a hadith stating that "In my community there will rise a man called Abu Hanifa [the Hanafite founder] who will be its guiding light". In fact one agreed upon hadith warned that, "There will be forgers, liars who will bring you hadiths which neither you nor your forefathers have heard, Beware of them."<ref name=Goldziher-1967-127>{{cite book|last1=Goldziher|first1=Ignác|title=Muslim Studies, Vol. 1|date=1967|publisher=SUNY Press|page=127}} {{ISBN|0873952340}}</ref> In addition the number of hadith grew enormously. While [[Malik ibn Anas]] had attributed just 1720 statements or deeds to the Muhammad, it was no longer unusual to find people who had collected a hundred times that number of hadith.{{citation needed|date=January 2016}}

{{multiple image

Line 161 ⟶ 158:

}}

Faced with a huge corpus of miscellaneous traditions supporting different views on a wide variety of controversial matters—some of them flatly contradicting each other—Islamic scholars of the Abbasid period sought to authenticate hadith. Scholars had to decide which hadith were to be trusted as authentic and which had been fabricated for political or theological purposes. To do this, they used a number of techniques which Muslims now call the [[hadith sciences|science of hadith]].<ref>Islam – the Straight Path, John Eposito, p.81</ref>

The earliest surviving hadith manuscripts were copied on papyrus. A long scroll collects traditions transmitted by the scholar and qadi 'Abd Allāh ibn Lahīʻa (d. 790).<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Khoury |first1=Raif Georges |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uFdPklB61kIC |title='Abd Allah ibn Lahi'a (97-174/715-790) |last2=Lahiah |first2=Abd Allah Ibn |last3=Lahīʻah |first3=ʻAbd Allāh Ibn |date=1986 |publisher=Otto Harrassowitz Verlag |isbn=978-3-447-02578-2 |language=fr}}</ref> A ''Ḥadīth Dāwūd'' (''History of David''), attributed to [[Wahb ibn Munabbih]], survives in a manuscript dated 844.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Munabbih |first1=Wahb ibn |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kmiRyAEACAAJ |title=Wahb b. Munabbih |last2=Khoury |first2=Raif Georges |date=1972 |publisher=Otto Harrassowitz Verlag |isbn=978-3-447-01469-4 |language=de}}</ref> A collection of hadiths dedicated to invocations to God, attributed to a certain Khālid ibn Yazīd, is dated 880-881.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tillier |first=Mathieu |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1343008841 |title=Supplier Dieu dans l'Égypte toulounide : Le florilège de l'invocation d'après Ḫālid b. Yazīd (IIIe/IXe siècle) |others=Naïm Vanthieghem |year=2022 |isbn=978-90-04-52180-3 |location=Leiden |oclc=1343008841}}</ref> A consistent fragment of the ''Jāmiʿ'' of the Egyptian Maliki jurist 'Abd Allāh ibn Wahb (d. 813) is finally dated to 889.<ref>{{Cite book |last=David-Weill |first=Jean |title=Le Djâmiʻ dʹIbn Wahb |publisher=Institut français d'archéologie orientale |year=1939–1948 |location=Cairo}}</ref>

Line 187 ⟶ 184:

Hadith as an Interpretation of the Holy Quran:

{{blockquote|Move not your tongue with it, to hasten with recitation of it. Indeed, upon Us is its collection and its recitation. So when We have recited it, then follow its recitation. Then upon Us is Interpretation. Surah Al Qiyamah, verse 16-1916–19.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Surah Al-Qiyamah {{!}} 2 of 4 {{!}} al-Q̈iyamah {{!}} Chapter: 75 - Quran O |url=https://qurano.com/en/75-al-qiyama/2/ |access-date=2022-09-16 |website=qurano.com |language=en}}</ref>}}

The mainstream sects consider hadith to be essential supplements to, and clarifications of, the Quran, Islam's holy book, as well as for clarifying issues pertaining to Islamic jurisprudence. [[Ibn al-Salah]], a hadith specialist, described the relationship between hadith and other aspects of the religion by saying: "It is the science most pervasive in respect to the other sciences in their various branches, in particular to jurisprudence being the most important of them."<ref>''Ulum al-Hadith'' by Ibn al-Salah, p. 5, Dar al-Fikr, with the verification of Nur al-Din al-‘Itr.</ref> "The intended meaning of 'other sciences' here are those pertaining to religion," explains Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, "Quranic exegesis, hadith, and jurisprudence. The [[hadith sciences|science of hadith]] became the most pervasive due to the need displayed by each of these three sciences. The need hadith has of its science is apparent. As for Quranic [[exegesis]], then the preferred manner of explaining the speech of God is by means of what has been accepted as a statement of Muhammad. The one looking to this is in need of distinguishing the acceptable from the unacceptable. Regarding jurisprudence, then the jurist is in need of citing as an evidence the acceptable to the exception of the later, something only possible utilizing the science of hadith."<ref name="Nukat">Ibn Hajar, Ahmad. ''al-Nukat ala Kitab ibn al-Salah'', vol. 1, p. 90. Maktabah al-Furqan.</ref>

=== Western scholarship ===

Western scholarly criticism of hadith began in colonial India in the mid 19th century with the works of [[Aloys Sprenger]] and [[William Muir]]. These works were generally critical of the reliability of hadith, suggesting that traditional Muslim scholarship was incapable of determining the authenticity of hadith, and that the hadith tradition had been corrupted by widespread fabrication of fraudulent hadith. The late 19th century work of [[Ignaz Goldziher]], ''[[Muhammedanische Studien]]'' (''Muslim Studies''), is considered seminal in the field of Western hadith studies. Goldziher took the same critical approach as Sprenger and Muir, suggesting that many hadith showed anachronistic elements indicating that they were not authentic, and that the many contradictory hadith made the value of the entire corpus questionable. The work of [[Joseph Schacht]] in the 1950s sought to obtain a critical understanding of the chains of transmission of particular hadith, focusing on the convergence of transmission chains of particular hadith back to a single "common link" from who all later sources ultimately obtained the hadith, who Schacht considered to be the likely true author of the hadith, which could allow dating of when particular hadith began circulating. This method is widely influential in Western hadith scholarship, though has received criticism from some scholars. Some modern scholars have contested Schacht's assertion that the "common links" were likely forgers of the hadith, instead suggesting that they were avid collectors of hadiths, though their arguments for this have been criticised by other scholars.<ref name=":0" />

==Studies and authentication==

{{MainSee|Hadith studies|Hadith sciences}}

Authenticity of a hadith is primarily verified by its chain of transmission (''isnad''). Because a chain of transmission can be a forgery, the status of authenticity given by Muslim scholars are not generally accepted by Orientalists or historians, who largely consider hadith to be unverifiable. Ignaz Goldziherr demonstrated that several hadiths do not fit the time of Muhammad chronologically and content-wise.{{cn|date = July 2024}} As a result, Orientalists generally regard hadiths as having little value in understanding the life and times of the historical Muhammad, but are instead valuable for understanding later theological developments in the Muslim community.<ref name=":0" /><ref>Lutz Berger "Islamische Theologie", Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG 2010 isbn 978-3-8252-3303-7 p. 29</ref> According to [[Bernard Lewis]], "inIn the early Islamic centuries there could be no better way of promoting a cause, an opinion, or a faction than to cite an appropriate action or utterance of the Prophet."<ref name="EMHME-80" /> To fight these forgeries, the elaborate tradition of [[hadith studiessciences]] was devised<ref name="EMHME-80">{{cite book |last1=Lewis|first1=Bernard |title=The End of Modern History in the Middle East |date=2011|publisher=Hoover Institution Press |pages=79–80|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tGzsn4snUyEC&q=hadith+bernard+lewis&pg=PA80|access-date=28 March 2018|isbn=9780817912963 }}</ref> to authenticate hadith known as ''ilm al jarh'' or ''ilm al dirayah<ref name="EMHME-80" />''<ref name=50-Nasr>Nasr, S.H. ''Ideals and Realities of Islam'', 1966, p.80</ref> Hadith studiesscience use a number of methods of evaluation developed by early Muslim scholars in determining the veracity of reports attributed to Muhammad. This is achieved by:

*the individual narrators involved in its transmission,

*the scale of the report's transmission,

Line 201 ⟶ 198:

*the routes through which the report was transmitted.

Based on these criteria, various classifications of hadith have been developed. The earliest comprehensive work in hadith studiesscience was [[Ramahurmuzi|Abu Muhammad al-Ramahurmuzi's]] ''al-Muhaddith al-Fasil'', while another significant work was [[Hakim al-Nishaburi|al-Hakim al-Naysaburi]]'s ''Ma‘rifat ‘ulum al-hadith''. Ibn al-Salah's [[Introduction to the Science of Hadith|''ʻUlum al-hadith'']] is considered the standard classical reference on hadith studiesscience.<ref name="H-EoI"/> Some schools of Hadith methodology apply as many as sixteen separate tests.<ref name="Shafi"/>

===Biographical evaluation===

Line 242 ⟶ 239:

With regard to clarity, Imam [[Ali al-Ridha]] has narrated that "In our Hadith there are Mutashabih (unclear ones) like those in al-Quran as well as Muhkam (clear ones) like those of al-Quran. You must refer the unclear ones to the clear ones."<ref name=Kafi2013/>{{rp|15}}

Muslim scholars have a long history of questioning the hadith literature throughout Islamic history. Western academics also became active in the field later (in [[Hadith studies]]), starting in 1890, but much more often since 1950.<ref>See Western scholarship section in [[Criticism of hadith]] re: Ignatz Goldziher, Josef Schacht, Patricia Crone, John Esposito, and Reza Aslan in particular.</ref>

Some Muslim critics of hadith even go so far as to completely reject them as the basic texts of Islam and instead adhere to the movement called [[Quranism]]. Quranists argue that the Quran itself does not contain an invitation to accept hadith as a second theological source alongside the Quran. The expression "to obey God and the Messenger", which occurs among others in 3:132 or 4:69, is understood to mean that one follows the Messenger whose task it was to convey the Quran by following the Quran alone. Muhammad is, so to speak, a mediator from God to people through the Quran alone and not through hadith, according to Quranists.<ref>{{cite web|title=DeRudKR - Kap. 27: Was bedeutet 'Gehorcht dem Gesandten'?|periodical=Alrahman|publisher=|url=https://www.alrahman.de/die-erfundene-religion-und-die-koranische-religion-kapitel-27-was-bedeutet-gehorcht-dem-gesandten/|url-status=|format=|access-date=|archive-url=|archive-date=|date=2006-03-06|language=de-DE|pages=|quote=}}</ref><ref>{{citation|surname1=Dr Rashad Khalifa|title=Quran, Hadith and Islam|publisher=Dr. Rashad Khalifa Ph.D.|date=2001|language=German|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z-jNDwAAQBAJ|access-date=2021-06-12

Line 249 ⟶ 246:

Among the most prominent Muslim critics of hadith in modern times are the Egyptian [[Rashad Khalifa]], who became known as the "discoverer" of the [[Quran code]] (Code 19), the Malaysian [[Kassim Ahmad]] and the American-Turkish [[Edip Yüksel]] (Quranism).<ref>Musa: ''Ḥadīth as scripture''. 2008, S. 85.</ref>

Western scholars, notably Ignaz Goldziher and Joseph Schacht among others, have criticised traditional [[hadith studiesscience]]s as being almost entirely focused on scrutinizing the chain of transmittors (''isnad'') rather than the actual contents of the hadith (''matn''), and that scrutiny of ''isnad'' cannot determine the authenticity of a hadith.<ref name="[183]-Coulson">N.J. Coulson, "European Criticism of Hadith Literature, in ''Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period'', editor A.F.L. Beeston et al. (Cambridge, 1983) "[the authentication of hadith] was confined to a careful examination of the chain of transmitters who narrated the report and not report itself. 'Provided the chain was uninterrupted and its individual links deemed trustworthy persons, the Hadith was accepted as binding law. There could, by the terms of the religious faith itself, be no questioning of the content of the report; for this was the substance of divine revelation and therefore not susceptible to any form of legal or historical criticism"</ref><ref name=":0" /><ref name="[Schacht-1950_163]">{{cite book |last1=Schacht |first1=Joseph |title=The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence |date=1950 |publisher=Clarendon |location=Oxford |page=163}}</ref> Many Western scholars suspect that there was widespread fabrication of hadith (either entirely or by the misattribution of the views of early Muslim religious and legal thinkers to Muhammad) in the early centuries of Islam to support certain theological and legal positions.<ref name=":0" /> In addition to fabrication, it is possible for the meaning of a hadith to have greatly drifted from its original telling through the different intepretationsinterpretations and biases of its varying transmitters, even if the chain of transmission is authentic.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hoyland |first=Robert |date=March 2007 |title=Writing the Biography of the Prophet Muhammad: Problems and Solutions |url=https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00395.x |journal=History Compass |language=en |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=581–602 |doi=10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00395.x |issn=1478-0542}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Citation |last=Görke |first=Andreas |title=Muhammad |date=2020-01-02 |work=The Wiley Blackwell Concise Companion to the Hadith |pages=75–90 |editor-last=Brown |editor-first=Daniel W. |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118638477.ch4 |access-date=2024-06-29 |edition=1 |publisher=Wiley |language=en |doi=10.1002/9781118638477.ch4 |isbn=978-1-118-63851-4}}</ref> While some hadith may genuinely originate from firsthand observation of Muhammad (particularly personal traits that were not of theological interest, like his fondness for [[tharid]] and sweets), Western scholars suggest that it is extraordinarily difficult if not impossible to determine which hadith accurately reflect the historical Muhammad.<ref name=":2" /> Hadith scholar [[Muhammad Mustafa Azmi]] has disputed the claims made by Western scholars about the reliability of traditional hadith criticism.<ref name="[Azmi-1996_154]">{{cite book |last1=Azmi |first1=Muhammad Mustafa |title=On Schacht's Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence |date=1996 |publisher=Islamic Texts Society |page=154}}</ref>

==See also==

Line 307 ⟶ 304:

=== Online ===

* [https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hadith Hadith Islam], in ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'', by Albert Kenneth Cragg, Gloria Lotha, Marco Sampaolo, Matt Stefon, Noah Tesch and Adam Zeidan

* [https://quotescrowdseekeveryday.com/hadithjumma-bymubarak-topicshadees-andin-adviceurdu-ofhadith-pbuhon-hadeesjumuah-nabvifriday-inwith-urduimages/ Hadith by Topics and advice of PBUH] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221222182540/https://quotescrowd.com/hadith-by-topics-and-advice-of-pbuh-hadees-nabvi-in-urdu/ |date=22 December 2022 }}

==External links==