Hypnosis: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Content deleted Content added

m |

m |

||

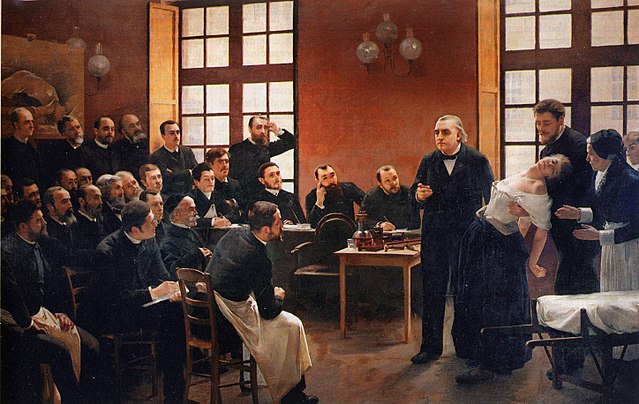

Line 25: === Precursors === People have been entering into hypnotic-type trances for thousands of years. In many cultures and religions, it was regarded as a form of meditation. The earliest record of a description of a hypnotic state can be found in the writings of [[Avicenna]], a Persian physician who wrote about "trance" in 1027.<ref name="SI Hall" /> Modern-day hypnosis started in the late 18th century and was made popular by [[Franz Mesmer]], a German physician who became known as the father of Mesmer held the opinion that hypnosis was a sort of mystical force that flows from the hypnotist to the person being hypnotised, but his theory was dismissed by critics who asserted that there is no magical element to hypnotism. Line 36: Last May [1843], a gentleman residing in Edinburgh, personally unknown to me, who had long resided in India, favored me with a letter expressing his approbation of the views which I had published on the nature and causes of hypnotic and mesmeric phenomena. In corroboration of my views, he referred to what he had previously witnessed in oriental regions, and recommended me to look into the ''Dabistan'', a book lately published, for additional proof to the same effect. On much recommendation I immediately sent for a copy of the ''Dabistan'', in which I found many statements corroborative of the fact, that the eastern saints are all self-hypnotisers, adopting means essentially the same as those which I had recommended for similar purposes.<ref>Braid, J. (1844/1855), "Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., etc. Historically and Physiologically Considered", [https://books.google.com/books?id=QB8CAAAAYAAJ&pg=PP7 ''The Medical Times'', Vol. 11] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162805/https://books.google.com/books?id=QB8CAAAAYAAJ&pg=PP7 |date=2 July 2023 }}, No. 272, (7 December 1844), pp. 203–04, No. 273, (14 December 1844), pp. 224–27, No. 275, (28 December 1844), pp. 270–73, No. 276, (4 January 1845), pp. 296–299, No. 277, (11 January 1845), pp. 318–20, No. 281, (8 February 1845), pp. 399–400, and No. 283, (22 February 1845), pp. 439–41: at [https://books.google.com/books?id=QB8CAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA206 p. 203] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162848/https://books.google.com/books?id=QB8CAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA206 |date=2 July 2023 }}.</ref>}} Although he rejected the transcendental/metaphysical interpretation given to these phenomena outright, Braid accepted that these accounts of Oriental practices supported his view that the effects of hypnotism could be produced in solitude, without the presence of any other person (as he had already proved to his own satisfaction with the experiments he had conducted in November 1841) {{blockquote|text= Line 49: In 1784, at the request of [[Louis XVI of France|King Louis XVI]], two [[Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism|Royal Commissions on Animal Magnetism]] were specifically charged with (separately) investigating the claims made by one Charles d'Eslon (1750–1786), a disaffected student of Mesmer, for the existence of a substantial (rather than metaphorical, as Mesmer supposed) "[[animal magnetism]]", ''''''le magnétisme animal'''''', and of a similarly physical "[[Animal magnetism#"Magnetizer"|magnetic fluid]]", ''''''le fluide magnétique''''''. Among the investigators were the scientist, [[Antoine Lavoisier]], an expert in electricity and terrestrial magnetism, [[Benjamin Franklin]], and an expert in pain control, [[Joseph-Ignace Guillotin]]. The Commissioners investigated the practices of d'Eslon From their investigations, both Commissions concluded that there was no evidence of any kind to support d'Eslon's claim for the [[Abstract and concrete|substantial physical existence]] of either his supposed "animal magnetism" or his supposed "magnetic fluid" <!-- Benjamin Franklin wrote: "This fellow Mesmer is not flowing anything from his hands that I can see. Therefore, this mesmerism must be a fraud." {{citation needed|date=April 2021}} --> Line 78: ==== Hysteria vs. suggestion ==== For several decades, Braid's work became more influential abroad than in his own country, except for a handful of followers, most notably Dr. [[John Milne Bramwell]]. The eminent neurologist Dr. [[George Miller Beard]] took Braid's theories to America. Meanwhile, his works were translated into German by [[William Thierry Preyer]], Professor of Physiology at [[Jena University]]. The psychiatrist [[Albert Moll (German psychiatrist)|Albert Moll]] subsequently continued German research, publishing ''Hypnotism'' in 1889. France became the focal point for the study of Braid's ideas after the eminent neurologist Dr. [[Étienne Eugène Azam]] translated Braid's last manuscript (''On Hypnotism'', 1860) into French and presented Braid's research to the French [[Academy of Sciences]]. At the request of Azam, [[Paul Broca]], and others, the [[French Academy of Science]], which had investigated Mesmerism in 1784, examined Braid's writings shortly after his death.<ref>{{cite book | last = Braid | first = James | editor = Robertson, D. | title = The Discovery of Hypnosis: The Complete Writings of James Braid, the Father of Hypnotherapy | year = 2009 | publisher = UKCHH Ltd. | page = 23 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Vs35STwQYQoC | isbn = 978-0-9560570-0-6 | access-date = 7 November 2015 | archive-date = 2 July 2023 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162805/https://books.google.com/books?id=Vs35STwQYQoC | url-status = live }}</ref> Azam's enthusiasm for hypnotism influenced [[Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault]], a country doctor. [[Hippolyte Bernheim]] discovered Liébeault's enormously popular group hypnotherapy clinic and subsequently became an influential hypnotist. The study of hypnotism subsequently revolved around the fierce debate between Bernheim and [[Jean-Martin Charcot]], the two most influential figures in late 19th-century hypnotism. | |||