Susa: Difference between revisions - Wikipedia

Article Images

Article Images

Line 8:

|native_name = {{lang|fa|شوش}}

|alternate_name =

|image = History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria (1903) (14584070300).jpg

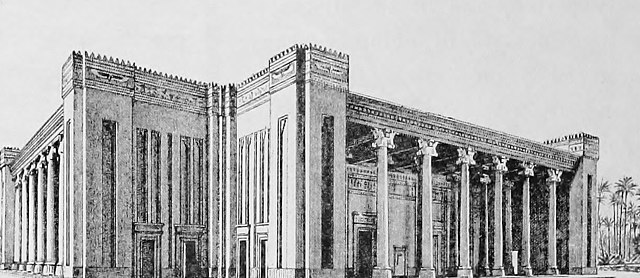

|image = King's apartments Apadana Susa.jpg

|alt =

|caption = [[Palace of Darius in Susa|The Palace of [[Darius I]] in Susa]]

|map_type = Iran#West Asia

|map_alt =

Line 27:

|builder =

|material =

|built = 4200 BCE<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.worldhistory.org/timeline/susa/ |title= Susa timeline |last= |first= |date= |website= |publisher= |access-date= |quote=}}</ref>

|built = 4400 BC

|abandoned = 1218 ADCE

|epochs = <!-- actually displays as "Periods" -->

|cultures =

Line 47:

| criteria = Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv}}

}}

'''Susa''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|uː|s|ə}} {{respell|SOO|sə}}; Middle {{lang-elx|𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗|translit=Šušen}};{{sfn|Hinz|Koch|1987|page=[https://archive.org/details/ElamischesWorterbuch.2/page/n449/mode/2up 1184]}} Middle and Neo-{{lang-elx|𒋢𒋢𒌦|translit=Šušun}};{{sfn|Hinz|Koch|1987|page=[https://archive.org/details/ElamischesWorterbuch.2/page/n449/mode/2up 1184]}} Neo-[[Elamite language|Elamite]] and [[Achaemenid Empire|Achaemenid]] {{lang-elx|𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭|translit=Šušan}};{{sfn|Hinz|Koch|1987|page=[https://archive.org/details/ElamischesWorterbuch.2/page/n449/mode/2up 1183]}} [[Achaemenid Empire|Achaemenid]] {{lang-elx|𒀸𒋗𒐼|translit=Šuša}};{{sfn|Hinz|Koch|1987|page=[https://archive.org/details/ElamischesWorterbuch.2/page/n449/mode/2up 1183]}} {{lang-fa|شوش}} {{transliteration|fa|Šuš}} {{IPA-|fa|ʃuʃ|}}; {{lang-he|שׁוּשָׁן}} {{transliteration|he|Šūšān}}; {{lang-grc-gre|Σοῦσα}} {{transliteration|grc|Soûsa}}; {{lang-syr|ܫܘܫ}} {{transliteration|syr|Šuš}};<ref>Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Susa — ܫܘܫ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified June 30, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/415.</ref> {{lang-pal|𐭮𐭥𐭱𐭩}} {{transliteration|pal|Sūš}} or {{lang|pal|𐭱𐭥𐭮}} {{transliteration|pal|Šūs}}; {{lang-peo|𐏂𐎢𐏁𐎠}} {{transliteration|peo|Çūšā}}) was an ancient city in the lower [[Zagros Mountains]] about {{convert|250|km|mi|abbr=on}} east of the [[Tigris]], between the [[Karkheh River|Karkheh]] and [[Dez River|Dez]] Rivers in Iran. One of the most important cities of the [[Ancient Near East]], Susa served as the capital of [[Elam]] and the winter capital of the [[Achaemenid Empire]], and remained a strategic centre during the [[Parthian Empire|Parthian]] and [[Sasanian Empire|Sasanian]] periods.

The site currently consists of three archaeological mounds, covering an area of around one square kilometre{{convert|1|sqkm|sqmi}}.<ref>{{cite book|author1=John Curtis|editor1-last=Perrot|editor1-first=Jean|editor1-link=Jean Perrot|title=The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia|date=2013|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=9781848856219|page=xvi|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fDimj7F2VVgC&q=Shush+Susa&pg=PR16|language=en|chapter=Introduction}}</ref> The modern Iranian towncity of [[Shush, Iran|Shush]] is located on the site of ancient Susa. Shush is identified as Shushan, mentioned in the [[Book of Esther]] and other Biblical books.

== Name ==

Line 97:

In [[urban history]], Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of the region. Based on calibrated [[carbon-14 dating]], the foundation of a settlement there occurred as early as 4395 BC.<ref>Potts: ''Elam'', pp. 46.</ref> In the region around Susa were a number of towns (with their own platforms) and villages that maintained a trading relationship with the city, especially those along the Zagro frontier.<ref>Wright, Henry T., "The Zagros Frontiers of Susa during the Late 5th Millennium", Paléorient, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 11–21, 2010</ref>

The founding of Susa corresponded with the abandonment of nearby villages. Potts suggests that the settlement may have been founded to try to reestablish the previously destroyed settlement at [[Chogha Mish]], about 25 km to the west.<ref name="Potts: Elam">Potts: ''Elam''.</ref> Previously, [[Chogha Mish]] was a very large settlement, and it featured a similar massive platform that was later built at Susa.<ref name=":1">{{citationCite book |last=Alizadeh |first=Abbas |url=https://www.worldcat.org/title/ocm53122624 |title=Excavations at the prehistoric mound of Chogha Bonut, Khuzestan, Iran: seasons 1976/77, 1977/78, and 1996 needed|date=April2003 2023|publisher=Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in Association with the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization |isbn=978-1-885923-23-3 |series=University of Chicago Oriental Institute publications |location=Chicago, Ill |oclc=ocm53122624}}</ref>

Another important settlement in the area is [[Chogha Bonut]], which was discovered in 1976.{{citation<ref needed|datename=April":1" 2023}}/>

=== Susa I period (4200–3800 BC) ===

Line 111:

Painted ceramic vessels from Susa in the earliest first style are a late, regional version of the Mesopotamian [[Ubaid period|Ubaid]] ceramic tradition that spread across the Near East during the fifth millennium BC.<ref name="Aruz 1992 26"/> Susa I style was very much a product of the past and of influences from contemporary ceramic industries in the mountains of western Iran. The recurrence in close association of vessels of three types—a drinking goblet or beaker, a serving dish, and a small jar—implies the consumption of three types of food, apparently thought to be as necessary for life in the afterworld as it is in this one. Ceramics of these shapes, which were painted, constitute a large proportion of the vessels from the cemetery. Others are coarse cooking-type jars and bowls with simple bands painted on them and were probably the grave goods of the sites of humbler citizens as well as adolescents and, perhaps, children.<ref>{{cite book|last=Aruz|first=Joan|title=The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre|year=1992|publisher=Abrams|location=New York|page=29}}</ref> The pottery is carefully made by hand. Although a slow wheel may have been employed, the asymmetry of the vessels and the irregularity of the drawing of encircling lines and bands indicate that most of the work was done freehand.

==== Metallurgy ====

Copper metallurgy is also attested during this period, which was contemporary with metalwork at some highland Iranian sites such as [[Tepe Sialk]].

As many as 40 copper axes have been found at the Susa cemetery, as well as 10 round discs probably used as mirrors. Many awls and spatulas were also found.

: "Metal finds from the burials in Susa are the major metal assemblage from the end of the 5th millennium BCE. Strata 27 to 25 contained the earliest burials with a large number of axes, made from unalloyed copper and copper with elevated As [Arsenic] levels."<ref>Thomas Rose 2022, [https://iris.uniroma1.it/retrieve/5172909a-429c-4fc2-901d-f1e82b1465cb/Tesi_dottorato_Rose.pdf Emergence of copper pyrotechnology in Western Asia.] PhD thesis, Beer-Sheva. 342pp</ref><ref>Rosenstock, E., Scharl, S., Schier, W., 2016. Ex oriente lux? Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zur Stellung der frühen Kupfermetallurgie Südosteuropas, in: Bartelheim, M., Horejs, B., Krauß, R. (Eds.), Von Baden bis Troia, Oriental and European Archaeology. Leidorf, Rahden/Westf., pp. 59–122. p. 75</ref>

The cemetery of [[Chega Sofla]], from the same timeframe, provides a lot of similar material, with many sophisticated metal objects.<ref>Moghaddam, A., Miri, N., 2021. Tol-e Chega Sofla Cemetery: A Phenomenon in the Context of Late 5th Millennium Southwest Iran, in: Abar, A., D’Anna, M.B., Cyrus, G., Egbers, V., Huber, B., Kainert, C., Köhler, J., Öğüt, B., Rol, N., Russo, G., Schönicke, J., Tourtet, F. (Eds.), ''Pearls, politics and pistachios.'' Ex oriente, Berlin, pp. 47–60. https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.837.c10734</ref> Chega Sofla is located in the same geographical area.

* GALLERY - ceramic objects from Susa I

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4">

Louvre Suse I Boisseau décor géométrique 1 14012018.jpg

Line 144 ⟶ 152:

Susa III (3100–2700 BC) is also known as the '[[Proto-Elamite]]' period.<ref>D. T. Potts, [https://books.google.com/books?id=7lK6l7oF_ccC&pg=PA743 ''A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East.''] Volume 94 of Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons, 2012 {{ISBN|1405189886}} p. 743</ref> At this time, Banesh period pottery is predominant. This is also when the Proto-Elamite tablets first appear in the record. Subsequently, Susa became the centre of [[Elam]] civilization.

Ambiguous reference to Elam ([[Cuneiform]]; {{lang|sux|{{cuneiform|4|𒉏}} |translit=NIM}}) appear also in this period in [[Sumer]]ian records. Susa enters recorded history in the [[Early Dynastic Period of Sumer|Early Dynastic period of Sumer]]. A battle between [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]] and Susa is recorded in 2700 BC, when [[En-me-barage-si]] is said to have "made the land of Elam submit".<ref>Per [[Sumerian King List]]</ref>

<gallery widths="200px" heights="100px" perrow="4">

Line 154 ⟶ 162:

===Elamites===

[[File:Puzur-Inshushinak Ensi Shushaki in the "Table au Lion", Louvre Museum.jpg|thumb|left|''Puzur-Inshushinak Ensi Shushaki'' ({{lang|elx|{{cuneiform|elx|𒅤𒊭𒀭𒈹𒂞 𒑐𒋼𒋛 𒈹𒂞𒆠}}}}), "[[Puzur-Inshushinak]] [[Ensi (Sumerian)|Ensi]] (Governor) of Susa", in the "Table au Lion", dated 2100 BC, Louvre Museum.<ref>Translation of the Akkadian portion into French, in {{cite book |title=Mémoires |date=1899 |publisher=P. Geuthner |location=Paris |pages=[https://archive.org/details/mmoires04franuoft/page/4 4]–7 |url=https://archive.org/details/mmoires04franuoft}}</ref>]]

In the [[Sumer]]ian period, Susa was the capital of a state called Susiana (Šušan), which occupied approximately the same territory of modern [[Khūzestān Province]] centered on the [[Karun|Karun River]]. Control of Susiana shifted between [[Elam]], Sumer, and [[Akkadian Empire|Akkad]].

Line 170 ⟶ 178:

| image1 = Dynastic list Awan Siwashi Louvre Sb17729.jpg

| image2=Awan Kings List Sb 17729 (transcription).jpg

| footer=Dynastic list of twelve kings of Awan dynasty and twelve kings of the [[Shimashki Dynasty]], 1800–1600 BC, Susa, [[Louvre Museum]] Sb 17729.<ref>{{cite web |title=Awan King List |url=https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/dynastic-list-kings-awan-and-simashki |access-date=2 August 2020 |archive-date=3 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210803163644/https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/dynastic-list-kings-awan-and-simashki |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=SCHEIL |first1=V. |title=Dynasties Élamites d'Awan et de Simaš |journal=Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale |date=1931 |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=1–46 |jstor=23283945 |issn=0373-6032}}</ref>

}}

The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by [[Enmebaragesi]], the [[Sumer]]ian king of [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]] in [[Mesopotamia]]. Three dynasties ruled during this period. Twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of [[Awan dynasty|Awan]] (or ''Avan''; c. 2400–2100 BC) and [[Shimashki Dynasty|Simashki]] (c. 2100–1970 BC), are known from a list from Susa dating to the [[First Babylonian dynasty|Old Babylonian period]]. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over parts of Sumer in very early times include Awan and [[Hamazi]]; and likewise, several of the stronger [[Sumer]]ian rulers, such as [[Eannatum]] of [[Lagash]] and [[Lugal-Anne-Mundu|Lugal-anne-mundu]] of [[Adab (city)|Adab]], are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam.

Line 179 ⟶ 187:

The city was subsequently conquered by the neo-Sumerian [[Third Dynasty of Ur]] and held until Ur finally collapsed at the hands of the Elamites under [[Kindattu]] in ca. 2004 BC. At this time, Susa was ruled by Elam again and became its capital under the Shimashki dynasty.

===Indus-Susa relations (2600–17002400–2100 BC)===

Numerous artifacts of [[Indus Valley civilization]] origin have been found in Susa from this period, especially seals and [[etched carnelian beads]], pointing to [[Indus-Mesopotamia relations]] during this period.<ref name="Site officiel du musée du Louvre">{{cite web|title=Site officiel du musée du Louvre|url=http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=13544|website=cartelfr.louvre.fr}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Marshall|first1=John|title=Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927|date=1996|publisher=Asian Educational Services|isbn=9788120611795|page=425|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ds_hazstxY4C&pg=PA425|language=en}}</ref>

<gallery widths="200px" heights="100px" perrow="4">

File:Susa seal with Indus signs.jpg|Impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa, in strata dated to 2600–17002400–2100 BC. Elongated buffalo with line of standard [[Indus script]] signs. [[Tell (archaeology)|Tell]] of the Susa acropolis. [[Louvre Museum]], reference Sb 2425.<ref name="Site officiel du musée du Louvre"/><ref>{{cite book|last1=Marshall|first1=John|title=Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927|date=1996|publisher=Asian Educational Services|isbn=9788120611795|page=425|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ds_hazstxY4C&pg=PA425|language=en}}</ref> Indus script numbering convention per [[Asko Parpola]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Corpus by Asko Parpola|url=http://www.mohenjodaroonline.net/index.php/indus-script/corpus-by-asko-parpola|website=Mohenjodaro|language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>Also, for another numbering scheme: {{cite book|last1=Mahadevan|first1=Iravatham|title=The Indus Script. Text, Concordance And Tables Iravathan Mahadevan|date=1987|publisher=Archaeological Survey of India|pages=32–36|url=https://archive.org/stream/TheIndusScript.TextConcordanceAndTablesIravathanMahadevan/The%20Indus%20Script.%20Text%2C%20Concordance%20and%20Tables%20-Iravathan%20Mahadevan#page/n41/mode/2up|language=en}}</ref>

File:Indus round seal with impression Elongated buffalo with Harappan scrpit imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE LOUVRE Sb5614.jpg|Indus round seal with impression. Elongated buffalo with Harappan script imported to Susa in 2600–17002340–2200 BC. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. [[Louvre Museum]], reference Sb 5614<ref>{{Cite web |title=Louvre Museum - cachet -2340 / -2200 (Akkad) - Lieu de création : Vallée de l'Indus - Lieu de découverte : Suse - SB 5614 ; AS 15374 |url=https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010179441}}</ref>

File:Indus carnelian beads with white design imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE LOUVRE Sb 13099.jpg|Indian [[carnelian]] beads with white design, etched in white with an alkali through a heat process, imported to Susa in 2600–17002400–2100 BC. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. [[Louvre Museum]], reference Sb 17751.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Guimet|first1=Musée|title=Les Cités oubliées de l'Indus: Archéologie du Pakistan|date=2016|publisher=FeniXX réédition numérique|isbn=9782402052467|pages=354–355|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-HpYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA354|language=fr}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus.|page=395|url=https://archive.org/details/ArtOfTheFirstCitiesTheThirdMillenniumB.C.FromTheMediterraneanToTheIndusEditedByJ/page/n419|language=en}}</ref> These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of [[Dholavira]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Nandagopal|first1=Prabhakar|title=Decorated Carnelian Beads from the Indus Civilization Site of Dholavira (Great Rann of Kachchha, Gujarat)|publisher=Archaeopress Publishing Ltd|isbn=978-1-78491-917-7|url=https://www.academia.edu/37860117|language=en|date=2018-08-13 }}</ref>

File:Indus bracelet made of Fasciolaria Trapezium or Xandus Pyrum imported front and back with inscribed chevron to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE LOUVRE Sb14473.jpg|Indus bracelet, front and back, made of ''[[Pleuroploca trapezium]]'' or ''[[Turbinella pyrum]]'' imported to Susa in 2600–17002400–2100 BC. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473.<ref>{{cite web|title=Louvre Museum Official Website|url=http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not&idNotice=13532|website=cartelen.louvre.fr}}</ref> This type of bracelet was manufactured in [[Mohenjo-daro]], [[Lothal]] and [[Balakot]].<ref name="FeniXX réédition numérique">{{cite book|last1=Guimet|first1=Musée|title=Les Cités oubliées de l'Indus: Archéologie du Pakistan|date=2016|publisher=FeniXX réédition numérique|isbn=9782402052467|page=355|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-HpYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA355|language=fr}}</ref> The back is engraved with an oblong chevron design which is typical of shell bangles of the Indus Civilization.<ref>{{cite book|title=Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus.|page=398|url=https://archive.org/details/ArtOfTheFirstCitiesTheThirdMillenniumB.C.FromTheMediterraneanToTheIndusEditedByJ/page/n422|language=en}}</ref>

File:Indus Valley Civilization carnelian beads excavated in Susa.jpg|Indus Valley Civilization carnelian beads excavated in Susa.

Jewelry with components from the Indus, Central Asia and Northern-eastern Iran found in Susa dated to 2600-1700 BCE, SB 13099.jpg|Jewelry with components from the Indus, Central Asia and Northern-eastern Iran found in Susa dated to 2600–17002400–2100 BC. Louvre - SB 13099 ; N 601.

</gallery>

====Middle Elamite period (c. 1500–1100 BC)====

[[File:Susa, Middle-Elamite basrelief of warrior gods 1600-1100 BCE.jpg|thumb|Middle-Elamite basrelief of warrior gods, Susa, 1600-11001600–1100 BC]]

Around 1500 BC, the Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties. Their rule was characterized by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While, previously, the Akkadian language was frequently used in inscriptions, the succeeding kings, such as the Igihalkid dynasty of c. 1400 BC, tried to use Elamite. Thus, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana.{{fact|date=January 2024}}

This was also the period when the Elamite pantheon was being imposed in Susiana. This policy reached its height with the construction of the political and religious complex at [[Chogha Zanbil]], {{convert|30|km|mi|0|abbr=on}} south-east of Susa.

Line 228 ⟶ 236:

Cyrus' conquest of Susa and the rest of Babylonia commenced a fundamental shift, bringing Susa under Persian control for the first time. [[Strabo]] stated that Cyrus made Susa an imperial capital though there was no new construction in that period so this is in dispute.<ref>Waters, Matt, "CYRUS AND SUSA", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie Orientale, vol.102, pp.115–18, 2008</ref>

Under Cyrus' son [[Cambyses II]], Susa became a center of political power as one of four capitals of the Achaemenid Persian empire, while reducing the significance of [[Pasargadae]] as the capital of Persis. Following Cambyses' brief rule, [[Darius the Great]] began a major building program in Susa and [[Persepolis]], which included building a large [[Palace of Darius in Susa|palace]].<ref>Unvala, J. M., "The Palace of Darius the Great and the Apadāna of Artaxerxes II in Susa", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, vol.5, no.2, pp.229–32, 1929</ref> During this time he describes his new capital in an inscription:

"This palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought. Downward the earth was dug, until I reached rock in the earth. When the excavation had been made, then rubble was packed down, some 40 cubits in depth, another part 20 cubits in depth. On that rubble the palace was constructed."<ref>Kent, Roland G., "The Record of Darius's Palace at Susa", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 1–23, 1933</ref>

Line 295 ⟶ 303:

File:ArtabanIIIGreekLetter.JPG|Letter in Greek of the Parthian king [[Artabanus II of Parthia|Artabanus II]] to the inhabitants of Susa in the 1st century AD (the city retained Greek institutions since the time of the [[Seleucid empire]]). [[Louvre Museum]].<ref>Epigraphy of Later Parthia, «Voprosy Epigrafiki: Sbornik statei», 7, 2013, pp. 276-284 [https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Letter-in-Greek-of-king-Artaban-II-to-the-inhabitants-of-Susa-Louvre-Museum_fig1_335679719]</ref>

File:Rose cup Susa Louvre MAOS53.jpg|Glazed clay cup: Cup with rose petals, 8th–9th centuries

File:AnthropoidUnidentified sarcophagusselucid Louvreanthropoid Sb14393sarcophagus.jpg|Anthropoid [[sarcophagus]]

File:Lion Darius Palace Louvre Sb3298.jpg|Lion on a decorative panel from [[Palace of Darius at Susa|Darius I the Great's palace]]

File:Male head wearing a head-band resembling king of Syria Antiochus III (223–187 BC), late 1st century BC–early 1st century AD, Louvre Museum (7462828632).jpg|Marble head representing [[Seleucid Empire|Seleucid]] King [[Antiochus III]] who was born near Susa around 242 BC.<ref name=" Jonsson, David J. 2005 566 ">{{cite book|author= Jonsson, David J.|title= The Clash of Ideologies|publisher= Xulon Press|year= 2005|page=566|isbn= 978-1-59781-039-5|quote= Antiochus III was born in 242 BC, the son of Seleucus II, near Susa, Iran. }}</ref>

Line 343 ⟶ 351:

* Poebel, Arno, "The Acropolis of Susa in the Elamite Inscriptions", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 125–40, 1933

* UNVALA, J. M., "Three Panels from Susa", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie Orientale, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 179–85, 1928

* {{cite book |last1= Westenholtz |first1= J. G. |last2= Guthartz |first2= L. Taylor |title= Royal Cities of the Biblical World |location= Jerusalem |publisher= Rubin Mass |year= 1996 |isbn= 978-9657027011}}</ref>

* Woolley, C. Leonard, "The Painted Pottery of Susa", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 1, pp. 35–50, 1928

Line 353 ⟶ 361:

* Elizabeth Carter, "Suse, Ville Royale", Paléorient, vol. 4, pp. 197–211, 1979 DOI: 10.3406/paleo.1978.4222

* Elizabeth Carter, "The Susa Sequence – 3000–2000 B. C. Susa, Ville Royale I", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 451–454, 1979

* Elizabeth Carter, "Excavations in Ville-Royale-I at Susa: The third Millennium B.C.", Cahiers de la DAFI, vol. 11, pp. 11–139, 1980

* Roman Ghirshman, "Cinq campagnes de fouilles a Suse (1946–1951)", In: Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie Orientale 46, pp 1–18, 1952

* Ghirshman, Roman, and M. J. STEVE, "SUSE CAMPAGNE DE L'HIVER 1964-1965: Rapport Préliminaire", Arts Asiatiques, vol. 13, pp. 3–32, 1966

* GHIRSHMAN, R., "SUSE CAMPAGNE DE L'HIVER 1965-1966 Rapport Préliminaire", Arts Asiatiques, vol. 15, pp. 3–27, 1967

* [[Florence Malbran-Labat]], "Les inscriptions royales de Suse: briques de l'époque paléo-élamite à l 'empire néo-élamite", Paris 1995.

* Laurianne Martinez-Sève, "Les figurines de Suse", Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris 2002, {{ISBN|2-7118-4324-6}}.

* de Mecquenem, R., "LES DERNIERS RÉSULTATS DES FOUILLES DE SUSE", Revue Des Arts Asiatiques, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 73–88, 1929

Line 394 ⟶ 402:

[[Category:Elam]]

[[Category:Elamite cities]]

[[Category:Former populated places in Khuzestan Provinceprovince]]

[[Category:Hebrew Bible cities]]

[[Category:Parthian cities]]