J. J. McAlester

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

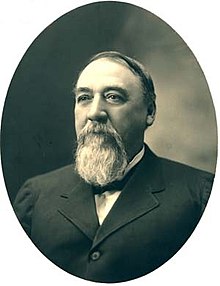

James Jackson McAlester (October 1, 1842 – September 21, 1920) was an American Confederate Army soldier and merchant. McAlester was the founder of McAlester, Oklahoma, as well as a primary developer of the coal mining industry in eastern Oklahoma. He served as the United States Marshal for Indian Territory (1893–1897), one of three members of the first Oklahoma Corporation Commission (1907–1911) and the second lieutenant governor of Oklahoma from 1911 to 1915.

James Jackson McAlester | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma | |

| In office January 9, 1911 – January 11, 1915 | |

| Governor | Lee Cruce |

| Preceded by | George W. Bellamy |

| Succeeded by | Martin E. Trapp |

| Oklahoma Corporation Commissioner | |

| In office November 16, 1907 – January 9, 1911 | |

| Governor | Charles N. Haskell |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | George A. Henshaw |

| United States Marshal for Indian Territory's Central District | |

| In office March 1, 1895 – April 19, 1897 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Jasper P. Grady |

| United States Marshal for Indian Territory | |

| In office April 6, 1893 – March 1, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas B. Needles |

| Succeeded by | Position replaced with multiple districts |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1, 1842 Sebastian County, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Died | September 21, 1920 (aged 77) McAlester, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Rebecca Burney |

| Relatives | Benjamin Burney (brother-in-law) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | |

Early life, military career, and family

McAlester was born in Sebastian County, Arkansas, on October 1, 1842, and grew up in Ft. Smith, Arkansas. He joined the Confederate States Army at the start of the war and reached the rand of captain.[1] He fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge.[2] After the defeat of the Confederacy he returned to Ft. Smith where he met engineer Oliver Weldon who gave him details of the location of coal deposits in Indian Territory (near now-McAlester, Oklahoma). In 1866 he moved to the Choctaw Nation and worked for the trading companies "Harlan and Rooks" and "Reynolds and Hannaford," before buying out the later.[1]

On August 22, 1872, he married Rebecca Burney (born 1841 in Mississippi - died May 5, 1919, in Oklahoma) a member of the Chickasaw Nation and they had five children.[3][4] Burney was the sister of Chickasaw Governor Benjamin Burney.[5] This made it possible for him to gain citizenship in and the right to own property in both the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations.[1]

Business Career and founding McAlester

By 1870, McAlester was running his own business at the "Crossroads" in Indian Territory, which later became McAlester, Oklahoma. He sold everyday goods and tools, and provided a stable supply of imported manufactured goods to Choctaw people in the area.[6] He lobbied Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad to bring the railroad through the Crossroads with trains first arriving in 1872. His role in bringing the railroads to the area led to the first post office for the area being dubbed "McAlester."[7]

Using the knowledge he had gotten from Weldon, McAlester was able to make many lucrative coal claims in the area and to establish what eventually became McAlester Coal Mining Co.[1] Since there was not enough labor in the Choctaw Nation to support the growing coal industry, immigrant workers from the United States and Europe were recruited to work in the mines, including a large Carpatho-Russian community.[8]

His trading company, J. J. McAlester Mercantile Company, was the unofficial company store for some miners since portions of their pay was issued in the form of scrip redeemable only at the store.[9] Some miners pay was also directly paid from the company to McAlester to cover debts or as store credit.[10] A review of his stores sale logs show price discrepancies between customers purchasing the same item, indicating some price discrimination, but no clear pattern of discrimination was determined.[11]

McAlester's selling of coal caused conflict with Choctaw Nation Chief Coleman Cole. Under Choctaw law, any tribal citizen who sold "part of the land" was to be sentenced to death and Cole interpreted the coal sales as a violation of the law. After McAlester was arrest by Choctaw Lighthorse alongside two other intermarried whites, the three men escaped.[12] McAlester claimed he later messaged Cole and settled the dispute, while other accounts say he lived in exile in the Muscogee Nation until the end of Cole's term in 1878.[a] In the 1880s, Green McCurtain led an unsuccessful effort to nationalize the Choctaw Nation's coal deposits.[15]

U.S. Marshall and Oklahoma Corporation Commission

On April 6, 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed McAlester U.S. Marshal for Indian Territory and he served until March 1, 1895, when he became the U.S. Marshall for Indian Territory's Central District until April 19, 1897.[16] He was elected to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission and took office in 1907. He did not run for reelection in 1910, instead running for Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma.[1]

Lt. Governor of Oklahoma and death

As a member of the Democratic Party he was elected as Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma with 118,544 votes (49.3%), winning against Republican Gilbert Dukes with 94,621 votes (39.4%), with Socialist candidate John G. Wills reaching nearly 10%.[17] During his tenure McAlester had the occasion to serve as acting governor of Oklahoma, during the absence of Governor Lee Cruce from the state, as evidenced by a pardon he issued in 1915 in the case of Sibenaler v. State (1915 OK CR 45).[18][original research?]

He died on September 21, 1920, in McAlester.[19]

McAlester House, J. J. McAlester's home in McAlester, Oklahoma, is on the National Register of Historic Places listings in Pittsburg County, Oklahoma.[20] A 2.5 ton chunk of coal sits from McAlester's mines was displayed at the 1921 World's fair, left in his yard for several years, and then given to McAlester High School where its been displayed outdoors since the mid-1980s.[21]

Analysis by historians

Historians' opinions of McAlester have shifted over time. Early to mid-twentieth century scholarship on his legacy was more likely to view him as a frontier businessman bringing civilization to Indian Territory, while later scholarship is more critical of his exploitation of Choctaw law and the effects of his business on the Choctaw Nation.[22] Historian Linda English described him as an "ambitious man who continually demonstrated his commitment to progress."[23]

J. J. McAlester's store served as the basis for the store visited by U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn in the 1968 novel True Grit by Charles Portis (and the subsequent 1969 and 2010 feature film versions).[24]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2023)

- ^ Paul Nesbitt wrote that McAlester settled the dispute with Cole, citing McAlester;[13] John Bartlett Meserve wrote that McAlester lived in the Muscogee Nation the remainder of Cole's term.[14]

- ^ a b c d e LaRadius, Allen (January 15, 2010). "McAlester, James Jackson (1842–1920)". okhistory.org. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Nesbitt 1933, p. 758.

- ^ "City of McAlester,OK". www.cityofmcalester.com. City of McAlester. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Gordon, James H.; Arnote, James S.; Freeman, W. P. (September 1927). "Necrology" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 5 (3). United States District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma: 352. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Cathey, Mike (3 July 2020). "The House that J.J. Built". McAlester News-Capital. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Hightower 2024, p. 148.

- ^ Hightower 2024, p. 149.

- ^ Hightower 2024, p. 149-150.

- ^ Orzano, Michele (February 1, 2015). "Obsolete note with a connection to 1968 novel True Grit". Coin World. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ English 2003, p. 42.

- ^ English 2003, p. 44-45.

- ^ Meserve 1936, p. 19.

- ^ Nesbitt 1933, p. 762-764.

- ^ Meserve 1936, p. 20.

- ^ Hightower 1984, p. 9.

- ^ "List of US Marshals - Oklahoma" (PDF). prod.usmarshals.gov. United States Marshals Service. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "1907-1912 Results" (PDF). oklahoma.gov. Oklahoma State Election Board. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Sibenaler v State (1915 OK CR 45). - The Oklahoma Supreme Court Network. - 15 May 1915.

- ^ "Fort Smith History: Sept. 19-25". Fort Smith Times Record. September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ State Historic Preservation Office listing for McAlester House Archived 2010-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. - Oklahoma Center for Geospatial Information (OCGI) at Oklahoma State University.

- ^ Culver, Galen (November 24, 2023). "A 2.5-ton sooty symbol stands as reminder of McAlester's coal mining history". KFOR-TV. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ English 2003, p. 35-36.

- ^ English 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Hoefling, Larry J. (2008). - "Pittsburg County". - Images of America. - Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. - pp.17-21. - ISBN 978-0-7385-5182-1.

- English, Linda C. (Spring 2003). "Inside the Store, Inside the Past: A Cultural Analysis of McAlester's General Store" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 81 (1): 34–53. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- Hightower, Michael J. (Spring 1984). "Cattle, Coal and Indian Land: A Tradition of Mining in Southeastern Oklahoma" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 62 (1): 4–25. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- Hightower, Michael J. (Summer 2024). "Old Reliable: The First National Bank of McAlester and the Extraordinary Legacy of Clark and Wanda Bass". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 102 (2): 147–164.

- Meserve, John Bartlett (Summer 1936). "Chief Coleman Cole" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 14 (1): 9–21. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- Nesbitt, Paul (Summer 1933). "J. J. McAlester" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 11 (2): 758–764. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Democratic nominee for Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma 1910 |

Succeeded by |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by | Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma 1911–1915 |

Succeeded by |