Middle kingdoms of Pakistan

Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Article Images

Article Images

political entities in Pakistan from 3rd century BC - 13th century AD

The Middle Kingdoms of Pakistan were the empires and kingdoms in the Greater Indus region from about 230 BCE to 1206 CE. This time starts after the Maurya Empire declined around 185 BCE and includes several regional powers and empires that influenced the area. The period begins with the influence of successor states such as the Indo-Greeks and Scythians, Huns, and later the Kushans.[1][2]

This "middle" era includes two different periods. The first, Classical Pakistan, starts from the decline of the Maurya Empire to the end of the Gupta Empire around 500 CE. It includes important changes in regional politics and culture.[3] The Gupta Empire was mainly in eastern India, it influenced the Greater Indus region through trade and cultural exchange.[4]

The second period, Early Medieval Pakistan, starts around 500 CE and continues through the rise of Islamic empires like the Umayyads, Ghaznavids, and Ghurids.[5] These empires played a important role in shaping the regional politics.[6] This time This period also includes the era of classical Hinduism, which is dated from approximately 200 BCE to 1100 CE.[7] The "middle" period lasted almost 1436 years and ended in 1206 CE with the start of the Delhi Sultanate.[8]

During the early part of this era, from 1 CE to around 1000 CE, Indo-Pakistan’s economy is thought to have been the largest in the world, holding between one-third and one-quarter of the world’s wealth.[9][10]

The Middle kingdoms

During the 2nd century BCE, after the Maurya Empire declined, the northwest part of the subcontinent (Pakistan) saw the rise of various regional powers with overlapping borders. This region experienced many invasions between 200 BCE and 300 CE. The Hindu religious texts, the Puranas, describe many of these invading tribes as "Mlecchas," a term used to mean foreigners.[11]

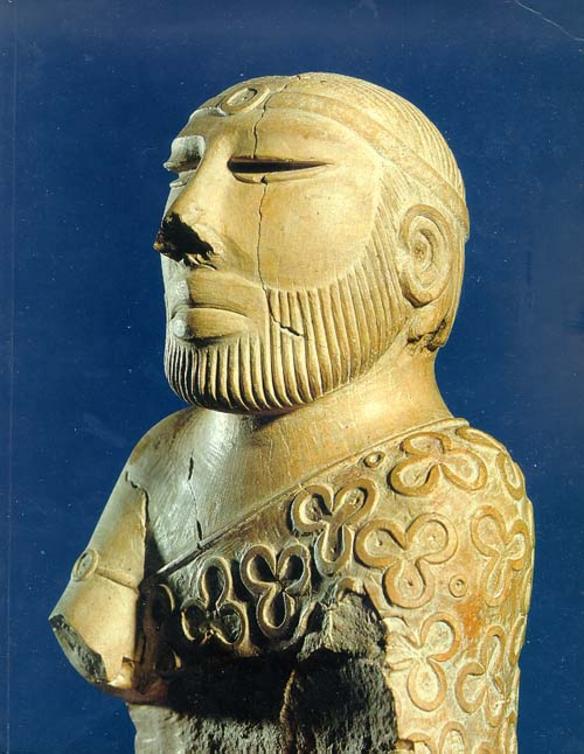

Many of these invading groups became influenced by Buddhism, which continued to grow with their support and helped mix different cultural traditions. Over time, these invaders blended into the local culture, leading to a time of intellectual and artistic achievements driven by cultural and religious syncretism (mixing). This period saw the development of Gandharan art, known for its first human images of the Buddha, and the growth of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism in the region.[12] The Gandhara art of Ancient Pakistan shows this unigue cultural blend and its importance along the Silk Road.[13]

The Indo-Greeks

The Indo-Greek Kingdom covered most of Pakistan from approximately 250 BCE to 10 CE and was ruled by over 30 Hellenistic kings, , who often fought with each other.

The kingdom was established when Demetrius I of Bactria invaded the Hindu Kush early in the 2nd century BCE. The Greeks in Pakistan eventually seperated from the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which was centered in Bactria (now the border between Afghanistan and Uzbekistan).

The term "Indo-Greek Kingdom" broadly refers to several dynastic families in the region. Important cities such as Taxila,[14] Pushkalavati (Charsadda), Purushapura (Peshawar) and Sagala (Sialkot) in Pakistan’s Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were capitals of these dynasties. According to Ptolemy’s Geography and the nomenclature of the later rulers, a place called Theophila in the south was likely an important administrative or royal center at some point.[15]

Euthydemus I, according to Polybius,[16] was a Greek from Magnesia. His son, Demetrius, who started the Indo-Greek kingdom, was Greek from his father. Demetrius married a daughter of Antiochus III the Great, who had some Persian ancestry.[17] The background of later Indo-Greek rulers is less clear.[18] For example, Artemidoros Aniketos (80 BCE) might have been of Indo-Scythian descent. There were also intermarriages among the Indo-Greeks.

During their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined Greek and South Asian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins. They also blended Greek, Hindu, and Buddhist religious practices, as shown by the archaeological remains of their cities and their support of Buddhism. This cultural syncretism (mix) led to a rich blend of local and Hellenistic influences.[19] The spread of Indo-Greek culture had lasting effects, especially through the influence of Greco-Buddhist art in Pakistan. The Indo-Greeks eventually disappeared as a ruling power around 10 CE after invasions by the Indo-Scythians, although some Greek people likely stayed for several more centuries under the Indo-Parthians and the Kushan Empire.[20]

The Indo-Scythians

The Indo-Scythians were a branch of the Sakas who migrated from southern Siberia into Bactria, Sogdia, and Ancient Pakistan (Arachosia, Gandhara, Kashmir, Punjab) from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE. The first Saka king in Pakistan was Maues or Moga who established Saka rule in Gandhara and gradually extended into other parts of eastern Pakistan. Indo-Scythian rule in Pakistan ended with the last of the Western Satraps, Rudrasimha III, in 395 CE.[21][22]

The Indo-Parthians

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was founded by Gondophares around 20 BCE. The kingdom lasted only briefly until its conquest by the Kushan Empire in the late 1st century CE and was a loose framework where many smaller dynasts maintained their independence.

The Western Satraps

The Western Satraps (35-405 CE) were Saka rulers of the Greater Indus region (Pakistan). Their state, or at least part of it, was called "Ariaca" according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. They were successors to the Indo-Scythians and were contemporaneous with the Kushan Empire, which ruled the northern part of Pakistan. They are called "Western" in contrast to the "Northern" Indo-Scythian satraps who ruled in the area of Mathura, such as Rajuvula, and his successors under the Kushans, the "Great Satrap" Kharapallana and the "Satrap" Vanaspara.[23] Although they called themselves "Satraps" on their coins, leading to their modern designation of "Western Satraps", Ptolemy's Geography still called them "Indo-Scythians".[24] Altogether, there were 27 independent Western Satrap rulers during a period of about 350 years.

The Kushans

The Kushan Empire (c. 1st–3rd centuries) originally formed in Bactria on either side of the middle course of the Amu Darya in what is now northern Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan; during the 1st century CE, they expanded their territory to include the Punjab and much of the Ganges basin, conquering a number of kingdoms across the northern part of the subcontinent in the process.[25][26] The Kushans conquered the central section of the main Silk Road and, therefore, had control of the overland trade between India, and China to the east, and the Roman Empire and Persia to the west.

The Kushans were great patron of Buddhism; however, as Kushans expanded into Gandhara and gained more influence the deities of their later coinage came to reflect syncretism of Hellenic and Buddhist influences.[27][28]

The Indo-Sasanians

The rise of new Persian power, the Sasanian Empire, saw them exert their influence into the Indus region and conquer lands from the Kushan Empire, setting up the Indo-Sasanians around 240 CE. They were to maintain their influence in the region until they were overthrown by the Rashidun Caliphate. Afterwards, they were displaced in 410 CE by the invasions of the Hephthalite Empire.

The Hephthalite Hunas

The Hephthalite Empire was another Central Asian nomadic group. They are also linked to the Yuezhi who had founded the Kushan Empire. From their capital in Bamyan (present-day Afghanistan) they extended their rule across Pakistan and parts of North India.

The Rais

The Rai dynasty of Sindh were patrons of Buddhism, they also established a huge temple of Shiva in Sukkur close to their capital, Aror.

The Gandharan kingdom

Gandhāra was an ancient region in the northwestern regions of Pakistan. It was also one of 16 Mahajanapada.[29][30][31]

The Karkotas

South Asia circa 700 CE.[32]

The Karkota Empire was established around 625 CE. During the eighth century they consolidated their rule over Kashmir.[33] The most illustrious ruler of the dynasty was Lalitaditya Muktapida. According to Kalhana's Rajatarangini, he defeated the Tibetans and Yashovarman of Kanyakubja, and subsequently conquered eastern kingdoms of Magadha, Kamarupa, Gauda, and Kaḷinga. Kalhana also states that he extended his influence of Malwa and Gujarat and defeated Arabs at Sindh.[34][35] According to historians, Kalhana highly exaggerated the conquests of Lalitaditya.[36][37]

The Kabul Shahis

The Kabul Shahi dynasties ruled portions of the Kabul valley and Gandhara from the decline of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century to the early 9th century.[38] The kingdom was known as the Kabul Shahan or Ratbelshahan from 565 CE-670 CE, when the capitals were located in Kapisa and Kabul, and later Udabhandapura, also known as Hund,[39] for its new capital in Pakistan. In ancient time, the title Shahi appears to be a quite popular royal title in the northwestern areas of the subcontinent. Variants were used much more priorly in the Near East,[40] but as well later on by the Sakas, Kushans Hunas, Bactrians, by the rulers of Kapisa/Kabul and Gilgit.[41] In Persian form, the title appears as Kshathiya, Kshathiya Kshathiyanam, Shao of the Kushanas and the Ssaha of Mihirakula (Huna chief).[42] The Kushanas are stated to have adopted the title Shah-in-shahi ("Shaonano shao") in imitation of Achaemenid practice.[43] The Shahis are generally split up into two eras—the Buddhist Shahis and the Hindu Shahis, with the change-over thought to have occurred sometime around 870 CE.

References

Citations

- ↑ Imam, Amna; Dar, Eazaz A. (2013-12-14). Democracy and Public Administration in Pakistan. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-1156-9.

... the classical period of its history during the Persian, Greek, Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian, Kushan, and Hun eras when the territories of present Pakistan...

- ↑ Ahmed, Mukhtar (2014-10-25). Ancient Pakistan - An Archaeological History: Volume V: The End of the Harappan Civilization, and the Aftermath. Amazon. ISBN 978-1-4997-0982-7.

- ↑ Romila Thapar, A History of India (1990).

- ↑ Qureshi, Ishtiaq Husain (1967). A Short History of Pakistan: Pre-Muslim period, by A. H. Dani. University of Karachi.

- ↑ Stein, B. (27 April 2010), Arnold, D. (ed.), A History of India (2nd ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 105, ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6

- ↑ Jackson, Peter (2003-10-16). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- ↑ Michaels, Axel (2004), Hinduism. Past and present, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 32, ISBN 0691089523

- ↑ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25119-8.

- ↑ "The World Economy (GDP): Historical Statistics by Professor Angus Maddison" (PDF). World Economy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Maddison, Angus (2006). The World Economy – Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective and Volume 2: Historical Statistics. OECD Publishing by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 656. ISBN 9789264022621. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ↑ Parasher, Aloka (1979). "The Designation Mleccha for Foreigners in Early India". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 40: 109–120. ISSN 2249-1937.

Mlecchas as a reference group in early India included all outsiders who did not conform to the values and ideas and consequently to the norms of the society accepted by the elite groups.

- ↑ Allon, Mark; Salomon, Richard (2010). "New Evidence for Mahayana in Early Gandhāra". The Eastern Buddhist. 41 (1): 1–22. ISSN 0012-8708.

- ↑ Samad, Rafi U. (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-859-2.

- ↑ Mortimer Wheeler Flames over Persepolis (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ff. It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a polis or with a Hippodamian plan.

- ↑ "Menander had his capital in Sagala" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies", p.83. McEvilley supports Tarn on both points, citing Woodcock: "Menander was a Bactrian Greek king of the Euthydemid dynasty. His capital (was) at Sagala (Sialkot) in the Punjab, "in the country of the Yonakas (Greeks)"." McEvilley, p.377. However, "Even if Sagala proves to be Sialkot, it does not seem to be Menander's capital for the Milindapanha states that Menander came down to Sagala to meet Nagasena, just as the Ganges flows to the sea."

- ↑ "11.34". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ "Polybius 11.34". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ Tarn, W. W. (1902). "Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 22: 268–293. doi:10.2307/623931. ISSN 0075-4269.

- ↑ "A vast hoard of coins, with a mixture of Greek profiles and Indian symbols, along with interesting sculptures and some monumental remains from Taxila, Sirkap and Sirsukh, point to a rich fusion of Indian and Hellenistic influences", India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p.130

- ↑ "When the Greeks of Bactria and India lost their kingdom they were not all killed, nor did they return to Greece. They merged with the people of the area and worked for the new masters; contributing considerably to the culture and civilization in southern and central Asia." Narain, "The Indo-Greeks" 2003, p. 278.

- ↑ Cunningham (1888), p. 33.

- ↑ Latif (1984), p. 56.

- ↑ Kharapallana and Vanaspara are known from an inscription discovered in Sarnath, and dated to the 3rd year of Kanishka, in which they were paying allegiance to the Kushanas. Source: "A Catalogue of the Indian Coins in the British Museum. Andhras etc..." Rapson, p ciii

- ↑ Ptolemy, Geographia, Chap 7

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. 29, 31.

- ↑ Hill (2004)

- ↑ Grégoire Frumkin (1970). Archaeology in Soviet Central Asia. Brill Archive. pp. 51–. GGKEY:4NPLATFACBB.

- ↑ Rafi U. Samad (2011). The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing. pp. 93–. ISBN 978-0-87586-859-2.

- ↑ Kulke, Professor of Asian History Hermann; Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- ↑ Warikoo, K. (2004). Bamiyan: Challenge to World Heritage. Third Eye. ISBN 978-81-86505-66-3.

- ↑ Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4.

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (f). ISBN 0226742210. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ Singh 2008, p. 571.

- ↑ Majumdar 1977, pp. 260–3.

- ↑ Wink 1991, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Chadurah 1991, p. 45.

- ↑ Hasan 1959, pp. 54.

- ↑ Shahi Family. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 16 October 2006 [1].

- ↑ Sehrai, Fidaullah (1979). Hund: The Forgotten City of Gandhara, p. 2. Peshawar Museum Publications New Series, Peshawar.

- ↑ Darius used titles like "Kshayathiya, Kshayathiya Kshayathiyanam" etc.

- ↑ The Shahi Afghanistan and Punjab, 1973, pp 1, 45-46, 48, 80, Dr D. B. Pandey; The Úakas in India and Their Impact on Indian Life and Culture, 1976, p 80, Vishwa Mitra Mohan - Indo-Scythians; Country, Culture and Political life in early and medieval India, 2004, p 34, Daud Ali.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1954, pp 112 ff; The Shahis of Afghanistan and Punjab, 1973, p 46, Dr D. B. Pandey; The Úakas in India and Their Impact on Indian Life and Culture, 1976, p 80, Vishwa Mitra Mohan - Indo-Scythians.

- ↑ India, A History, 2001, p 203, John Keay.

Sources

- Rafi U. Samad (2002). Greeks in Ancient Pakistan. Indus Publications. ISBN 9789695290019.

- Jadunath Sarkar (1960). Military History of India. Orient Longmans. ISBN 9780861251551.

- "Ancient, medieval & recent history and coins of Pakistan / by Sohail A. Khan - Catalogue | National Library of Australia". catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 2024-08-04.

- Khan, Yar Muhammad (1996). Recent Studies in Medieval History of Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent. Institute of Secular Studies, with special arrangement from S. Chand Publisher's Distributors, Beawar, Rajasthan.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2007). History of Pakistan: Pakistan Through Ages. Sang-e Meel Publications. ISBN 978-969-35-2020-0.

- Romila Thapar (1990-06-28). A History of India. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-194976-5.

- Agarwala, V. S. (1954). India as Known to Panini.

- Alexander Cunningham (1971). Coins of the Indo-Scythians, Sakas, and Kushans. Indological Book House. ISBN 978-8121222204.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.Weilue: The Peoples of the West Archived 23 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Latif, S.M., (1891) History of the Panjab, Reprinted by Progressive Books, Lahore, Pakistan, 1984.

- Chadurah, Haidar Malik (1991). History of Kashmir. Bhavna Prakashan.